Best-selling author Manu Pillai, who’s just come out with a new book about how the maharajas of Indian kingdoms held their own against the British, is one of a new generation of historians exploring the less-travelled routes of Indian history.

At the age of 31, he’s emerged as a sort of wunderkind among Indian historical writers -- he’s already got four books under his belt, including the very popular Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore and Rebel Sultans, a 400-year history of the Deccan. If that isn’t enough, he’s got an unfinished manuscript on his laptop and he’s studying for a PhD at King’s College London.

So, it’s hardly a surprise that Pillai admits to being a workaholic though he insists he’s figured the trick is to match discipline and time management. “It’s not as though I don’t have a social life though that was once upon a time the case. I’ve increasingly realised it’s simply about how you manage your time and whether you can discipline yourself,” Pillai says.

Pillai’s trademark is his ability to present historical tales to a lay history audience in an extremely readable package, shorn of academic denseness.

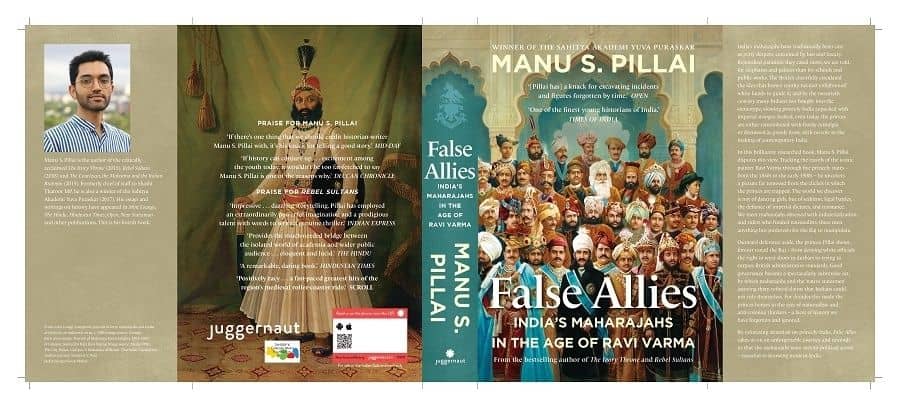

The central character in his newest work, False Allies: India’s maharajahs in the Age of Ravi Varma, who loosely brings the latest book together, is, of course, the famed painter Raja Ravi Varma.

The book is about five princely kingdoms where Raja Ravi Varma was invited to execute commissions and paint the maharajahs and their families – in all their bedazzling glory or as Western gentlemen who could run their kingdoms as efficiently and systematically as the British. Each of these kingdoms held its own against Queen Victoria’s imperial conquerors.

Inevitably, Pillai starts in his favourite kingdom, Travancore, the subject of his first book The Ivory Throne that thrust him to fame. From there he follows in the artist’s footsteps to Pudukottai, a smaller kingdom, which in its own quirky way, managed to move with the times and resist the British. Then, there’s Mysore, Baroda and, on a slightly different note, Jaipur.

Strangely, for a full-time historian and one studying for his PhD, Pillai didn’t do history as his main subject at Fergusson College in Pune. He did economics and admits he was more worried about a career at the time and didn’t think it was possible to earn a living from history. Later, he did a Master’s in International Relations at King’s College and thought that might be where his future lay. “In those days, I thought that would be my main career line and history would be a passion on the side,” he says.

But history as he puts it, “was always there.” Barely out of his teens, he had launched a blog and came across the tale of the last Travancore, Rani Sethulakshmi Bayi that everyone seemed to be eager to forget. Says Pillai: “A lot of older people began telling me, ‘Oh no, don’t go into that story. Lots of skeletons in the royal closet there’.” He adds cheerfully: “At the age of 18 when you’re told not to do something, you are likely to do the exact opposite.”

Transforming the blog into a book turned out to be a greater struggle than he had anticipated and there were months when he thought the project would collapse. During that time, he began work on another manuscript which is still locked away on his laptop. Six years later, Sethulakshmi Bayi’s story was published and became an instant bestseller. Pillai had discovered the rare skill of turning history into something readers would devour.

In the last decade, Pillai has moved to wherever history and the archives have taken him. He realised that he needed archives like the British Library so he persuaded his parents to send him to study in London. (There, he also worked with Lord Karan Bilimoria as a researcher). Later, he needed to spend time in Delhi and got a job working as chief of staff for Shashi Tharoor, another renowned writer as well as MP.

Pillai also worked for a time on a BBC programme on Indian history, which helped his finances. He says frankly: “The BBC project gave me more confidence about thinking of history as the main thing.” During this time, he got himself an agent, David Godwin, who represents authors like William Dalrymple, Claire Tomalin and Ian Jack as well as many of India’s top talents. Says Pillai: “I didn’t realise I had a reasonable market value till I got myself an agent. He’s the one who really shook sense into me. Before that, I didn’t even think much in terms of money.”

The books, combined with other smaller projects, have made him financially comfortable but he hasn’t got any taste for an extravagant lifestyle. For many years, he stayed in student accommodation. “Living in student halls was just easier and I only went there to sleep. The whole day I was in the library or archives.”

“I don’t drink much and I don’t party much and I don’t have extravagant tastes,” he says, adding: “I knew I wanted to travel to a certain archive. So I picked up certain habits, like figuring out how to budget and then do things within a budget.”

Before the pandemic shut down countries, Pillai returned to his parents in Pune, where he has lived from childhood. In his youth, his family travelled frequently to Kerala where he heard tales from his grandmother about life in the Travancore kingdom. That’s when he first began reading up on the Travancore rajas.

The Travancore royals were unusual in more ways than one. Firstly, they lived relatively straitlaced lives and didn’t have dancing girls in the court. Even more unusually, they weren’t about one-man rule. They had a bureaucratic network that provided a stable administration Later, kings spoke English fluently and took care to stay on the right side of the British so that their kingdom wasn’t confiscated by the rampantly expansionist colonial power.

While he speaks Malayalam, Pillai’s research on the Travancore royals was made infinitely easier by the fact most of the primary material was in English. “By the 1780s, you have the Travancore Maharaja speaking English. And in the late 19th century, the personal diaries, the maharajahs’ letters, those of the relatives, the rani, all of this is happening in English,” he says.

Luckily, for Pillai, he had stumbled in his youth on a relatively neglected sector of Indian history. Nehru detested the rajas and dismissed them as relics of the past and his daughter Indira Gandhi had even greater contempt for them and abolished their privy purses.

Still, though, the rajas were “an important part of India’s political landscape,” says Pillai. “If we’re to understand Indian history better, it’s important we move beyond the dancing girls and elephants at the palace. We should be a little bit more serious in the way we study the princely states because we may be surprised by the kinds of things we’ll find,” he says.

“The Rajput system, you know, was a very old political system that managed to sort of negotiate its way in the colonial period and last into the 20th century,” he says.

Travancore, Mysore and Baroda were kingdoms where the maharajas kept the British at bay by offering good governance and building up their states in different ways. These examples “tell us resistance to imperialism wasn't just about street agitation, there were other forms such as good governance because it punctured the idea that the natives could not rule,” Pillai says.

The Mysore maharajas – who were once deposed from their throne by the British – attempted to outdo their colonial masters with a spate of mega-projects. They built the Visveswaraya Steel Plant and dams and established the Kolar Goldfields in a bid to show they were as efficient and forward-thinking as the British.

Pillai says the mega-projects ultimately didn’t do much, though, for the man in the Mysore farms and villages. “Ninety per cent of the state’s subjects were villagers, but money was transferred disproportionately towards stylish industrial schemes to fulfil official ambitions.”

He adds: “Progress under the Wadeyars wasn’t just about keeping the British at a distance: there was a desire to set an example for India.” All this led one British resident to remark: “Without losing an atom of his nativeness, the ruler behaved ‘as if he were one of ourselves’.”

Baroda was forward-thinking in an entirely different way. Here, the maharaja established the Bank of Baroda, sugar mills and even declared that primary education would be free. He went further than all the other maharajas by diverting money to orphanages and boarding houses and scholarships for backward caste children.

Most famously, the majaraja awarded a scholarship to B. R. Ambedkar that enabled him to study abroad. He even told the Aga Khan: “I tell you there’ll never be an Indian nation until this so-called princely order disappears.” Says Pillai: “You would think that the maharajas were pillars of the empire, allies of the British. But why is it that the Baroda maharaja is secretly funding the Congress Party and secretly funding Dadabhai Naoroji’s election in London?”

Pillai adds: “You know, the Maharajah goes around meeting revolutionaries. He gives speeches about national culture, national feeling and national government in the future. This man is no pushover. This man is not some kind of pillar of the Raj. If he is a pillar in a structural sense, he's very shaky pillar.”

He says the Baroda experience was not unique and that a lot of princely states “were able to counter-manipulate the Raj to a great extent.”

Raja Ravi Varma even travelled all the way to Jaipur. But it’s clear that Pillai isn’t quite as enthusiastic about this state as the others. Under which of these rulers would he have preferred to live? Says Pillai: “I suppose Travancore’s not a bad place to have probably lived in. I definitely would not want to live in Rajputana.”

One of Pillai’s books was about the Deccan in the early modern era but it’s the colonial era that interests him the most. “I find this whole overlap of a foreign ruling class and the kind of effects it had on India in so many ways at so many levels, whether it's religion, society, politics, even the way we think. It’s an extremely fascinating chapter in our history. So I generally work on that period.”

As for the rajas, till the 1930s it was thought there would be a place at the table for them -- possibly in a royal upper house. But they were too divided. “The rajas never became a unified force, even to lobby. The Nizam of Hyderabad would not sit with the Patiala Maharaja because he thought he was too inferior. Travancore would not sit with Cochin because Cochin was two steps down in the hierarchy,” Pillai notes.

“The rajas still assumed their states would remain autonomous. The problem is World War Two comes along, the Federation negotiations are dropped as there are bigger things happening,” says Pillai. “At the end of the war, Britain just wants to leave. Partition’s looming and the Rajas are no longer equal stakeholders at the table,” he says. Also, Congress politicians, like Nehru, were deeply antagonistic towards the rajas.

Pillai’s doesn’t like to discuss his future projects, saying he’s a bit superstitious. In fact, he prefers not to talk about them till they’re actually with his publisher. “I’ve got another half-done manuscript which I have to return to,” he says, without divulging the subject. "People assume you go one at a time but, in my case, I’m juggling projects all at once.”