While he avoids being judgmental, opinions are not altogether absent. But they are either attributed to someone else (like the wry comment about the “Rig Veda” explaining successive Left Front election victories) or so nuanced as almost to be overlooked. When Kishan Chand, Delhi’s former lieutenant-governor, an Indian Civil Service officer whom the Shah Commission gave a rough time, was found dead in an abandoned well two kilometres from his South Delhi home, leaving two suicide notes, the police had no doubt he had killed himself. But Basu’s “allegedly committed suicide” recalls India Today’s report that “a host of prominent politicians seem equally convinced” he “was murdered to stop him from giving evidence against Mrs Gandhi and her Emergency cohorts”. He is more forthright about the Left Front’s stand on English. “An extreme view started gaining ground that the Left Front wanted the masses to remain uneducated so that they could be manipulated and prevented from questioning the system.”

Detailed case histories make this a valuable addition to the literature on a bureaucracy considered one of the world’s most powerful. But it would have benefited from professional editing, some fact-checking (How can a Paris city tour include the Vatican, or Bulgaria have been “a constituent of the USSR”?) and an Index. A more detailed analysis of the IAS’s role in contemporary India, possibly compared to those whom Philip Woodruff — Philip Mason of the ICS — immortalized as the Founders and Guardians, might also have added value to the volume. Basu’s definition of the IAS being “about sharing space with colleagues and the highest in the land, and knowing them better” echoes Lee Kuan Yew’s belief that only “an elite administration” can effectively “run a vast country like India”.

This now unfashionable view was ridiculed in a History Today writer’s mockery, “Much nonsense has been written about the romantic, glamorous notion of a single ICS officer riding around his district, dispensing even-handed justice to a grateful and submissive peasantry. Settling law cases before breakfast, such a paragon apparently corrected land records before lunch, shot a tiger or two before dinner and wrote some Latin verse before taking a cold bath and retiring to a camp bed.” Basu’s indulgence is Hindi film songs. References to the “steel frame”, Lloyd George’s term for the ICS, perpetuate that heaven-born mystique. Dipak Rudra, two years Basu’s senior in the IAS, more realistically called it the “bamboo frame” in several newspaper articles. That suggested a cadre that is more vulnerable to pressure, persuasion and all the weaknesses from which Indian institutions suffer.

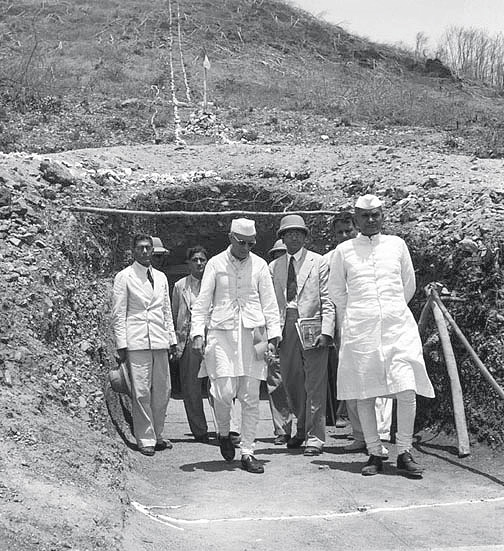

Basu rightly says Nehru “had a clear perception of the India he wished to create” but may err in claiming that “the senior officialdom advised him (Nehru) impartially to enable him fulfil his dream”. Nehru himself did not feel his dream was fulfilled. Asked three years before he died to identify his greatest failure, he replied after a long reflection, “I failed to change this administration. It is still a colonial administration.” Tarzie Vittachi, his Sri Lankan interlocutor, felt that for Nehru, the IAS was too much like the ICS.

Told by a sycophantic colleague that crime had gone down significantly since he became West Bengal’s chief minister and that there were “fewer robbers and dacoits” about, Bidhan Chandra Roy replied, “No wonder. Some of them are in my government.” Many such anecdotes enliven what might otherwise have been a somewhat solemn account of Ashok Basu’s 42 years as a civil servant in the state and Central governments.

Not many bureaucrats have such varied experiences in so many vital ministries, shape crucial developments like deregulation and decontrol in the iron and steel industry, or ensure transparency and accountability in electricity regulation. The reader shares his pleasure in these achievements and in his and his family’s academic brilliance and his father’s professional reputation as a policeman. Basu emerges as a thoroughly nice family man who bears no grudges and casts no stones. One wonders how his colleagues — not always one happy family — responded to this panglossian (“all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds”) benignity. Calcutta Corporation’s unions did not take kindly in 1983 to his plan as commissioner to engage Thames Water to restore the city’s sewage system which it had helped to lay a century earlier. They might have sung a different tune if China Investment Corporation had already bought 9 per cent of Thames equity which it didn’t do until about 20 years later.

Power, Duty and the Game Changer: Reflections of a Civil Servant By Ashok Basu, Mitra & Ghosh, Rs 400