Capetown born J.M. Coetzee, 83 this year, is an extraordinary writer. And he is notoriously media shy — one of the reasons for his superstardom being under wraps. Possibly more than any other writer of our times, he understands and explains the tangled web of racial politics, patriarchal domination of the female body and the horror of brutality towards animals with a directness and lyricism that stuns.

He is himself his best competition and after two Booker Prizes, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003. He dedicated the award to his mother, who has appeared and reappeared in many inventive characters in several of his pieces of fiction and non-fiction.

Coetzee speaks many European languages and has been actively involved in translating works to Dutch, German and Spanish. He is a specialist in many disciplines and is an academic who has studied mathematics and taught literature. He relocated to Australia in 2006 from South Africa, having lived in the US and Europe before that.

In April 2004, Coetzee was nominated for the Christine Stead Prize for fiction, one of the New South Wales Literary Awards, which is one of Australia’s top literary events. The event marked the first time that a Nobel laureate had been nominated for one of the awards. He also was on the shortlist for Australia’s Miles Franklin Literary Award for his 2003 novel Elizabeth Costello.

That same month, five of Coetzee’s novels were released in China for the first time. The books included Waiting for the Barbarians, Youth, and Disgrace. As a white South African, Coetzee witnessed, lived and was baffled by unconscionable crimes that were generously meted out to the Blacks for decades.

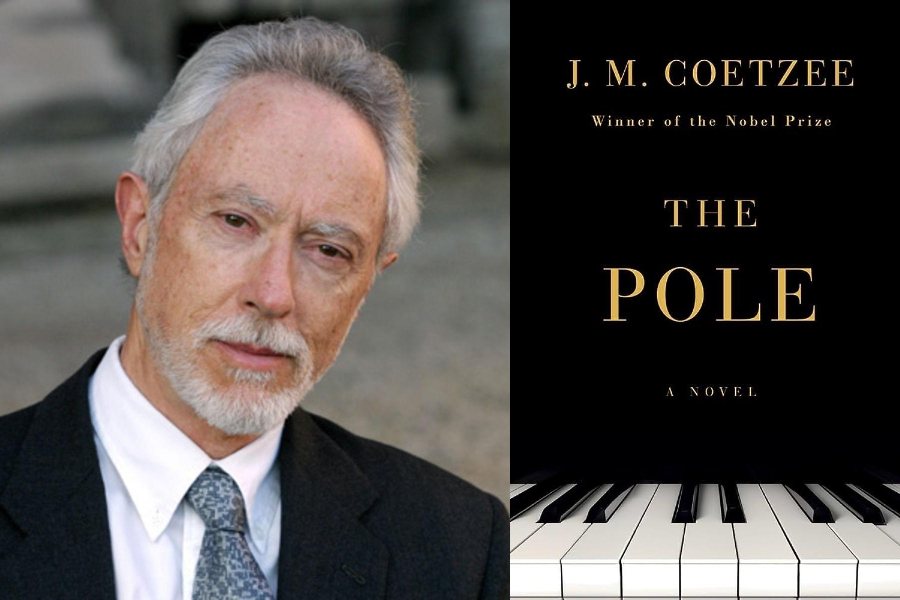

J.M. Coetzee at a book signing event at the Buenos Aires Book Fair. In recent times, the author has purposely published his new work first in the Southern Hemisphere.

Perhaps Foe (1997), a retelling of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, is Coetzee’s most read and discussed novel. It tells the story of the mute Friday, whose tongue was cut out by slavers, and Susan Barton, the castaway who struggles to communicate with him. The text is superbly constructed and lampoons the idea of the civilised White man.

Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, about oppression and unspeakable terror unleashed on the female body, is yet another appropriate text that students find complex and relatable to the narratives by Dalit writers, about the inhuman treatment of Dalit women by men from higher castes.

The novel Disgrace was published in 1999 to much contradictory feedback and is, perhaps, the most complex and popular of all his novels. Centring on the rape of Lucy, a young, gay, white South African woman, by three Black men, it might be seen to be a response to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Report incentive. In fact, it shows beyond reasonable doubt that there is often no way in which legislation can solve the real issues.

For example, Lucy’s active opacity and illegibility in her case, where she refuses to go to the police and make a report because she felt in some way she was paying back a debt of her ancestors as White men who raped hundreds and thousands of Black women had added up.

The novel offers a framing of history that is structured through the economy of debt. What debts must be paid for the violence of history, who has the right to collect them?…”They will come back… What if that is the price one has to pay for staying on?... They see me as owing something. They see themselves as debt collectors, tax collectors... Why should I be allowed to live here without paying?” However, in the end, its insistence upon the indeterminate status of justice is paradoxically what enables its ethical and political force.

To read Boyhood (1997), his lucid revisiting of his early days, is to open a window to Coetzee’s most impressionable years. In his recollection, the manner in which Coetzee makes sense of his past, is gripping. He revisits the South Africa of 80-odd years ago, to write about his childhood and inner life. And he describes that life in Boyhood.

His father’s law practice appears to be flourishing but his mother doesn’t seem to care because she is more concerned about people who owe his father money. For example, the car salesman who promises to pay by the end of the month, but he does not settle. Still, his father craves approval and there are only two ways to be liked in the circle in which he moves: one is to buy people free drinks and the other is to lend them money.

So, in the bar at the Fraserburg Hotel, Coetzee and his brother are sitting in a corner sipping orange juice, watching their father buy rounds of brandy for strangers and he sees the mood of expansive bonhomie that brandy creates in him, the boasting, the large spendthrift gestures. Besides the car salesman, there are other companions, other men that their father has been lending money. Coetzee cannot understand it, where does this money come from, when his father has only one tie and one suit and has to take the train to work.

Money, it turns out, is not actually his father’s. The matter is serious. The money is from his father’s trust account, where clients put their money on trust that they have for their attorneys. But his mother says God only knows why. “Jack is like a child when it comes to money. But the authorities at the law society want to save his father. They don’t want him to go to jail. And because of his wife and children they will turn a blind eye and allow him to make payments over five years.” But his mother takes legal advice independently.

Coetzee’s respect and regard for his mother, her huge, pervasive influence on him and her appearance as a powerful female character in many of his works are excellent examples of his appreciation of the tougher challenges women face in our evolving world. A deceptively simple style often houses the most complex challenges and nuances women must encounter and overcome in Coetzee’s stories.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College