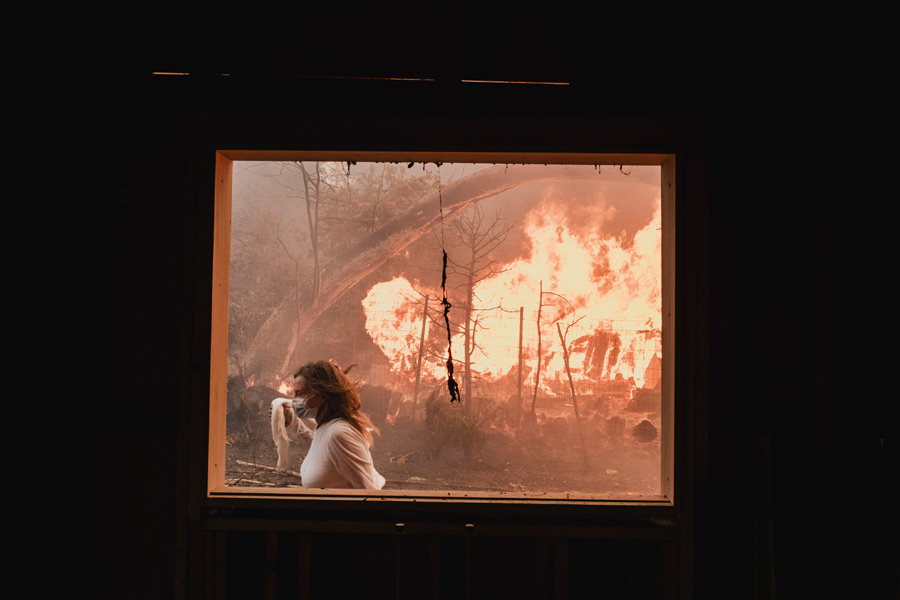

In the book’s most moving passage, Ullekh N.P. describes a crematorium and a graveyard near the beach in Payyambalam to suggest that the legacy of a political feud — the bloodletting between the Left and the Right in Kannur — transcends death. For the departed lie divided even in the afterlife. “The graves on the left... are those of the leftist men... while those on the right are those of leaders and workers of the Congress, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Bharatiya Janata Party.”

Ullekh’s chronicling of the political violence in Kannur is faithful to history. He recounts numerous incidents to suggest that the strife between the CPI(M) and the RSS — 200 people have been killed in the violence between 1972 and 2017 — had been preceded by an equally grisly confrontation between the Marxists and the Congress. It could not have been easy for Ullekh to remain objective in his assessment: he is the son of a Marxist leader. But Ullekh’s tone, to his credit, betrays neither emotion nor prejudice.

Where Ullekh falters, however, is in positing a likely explanation for the embedded culture of violence. For a veteran journalist, he inexplicably devotes an entire chapter to the inferences drawn by Alexander Jacob, an experienced police officer, to dissect the “anatomy of a conflict”. This in spite of Ullekh’s own admission that serious researchers have been contemptuous of Jacob’s analysis. Among other ‘causes’, Jacob has cited the ‘martial nature of the people of Kannur’ to explain the festering conflict. Ullekh writes that Jacob cites demography, geography, weather and — this is revealing — the infirmities within the police as the other catalysts.

Ullekh is not entirely dismissive of Jacob’s novelty. He suggests that ceding leadership to “peaceniks” and women could neutralize the toxic masculinity of Kannur’s politics. To the more discerning mind, the answer to resolving the crisis in Kannur may lie in improving conviction rates, mobilizing public opinion and instituting a neutral, fleet-footed bureaucratic apparatus sworn to break the nexus between crime and politics.

Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics By Ullekh N.P., Viking, Rs 499