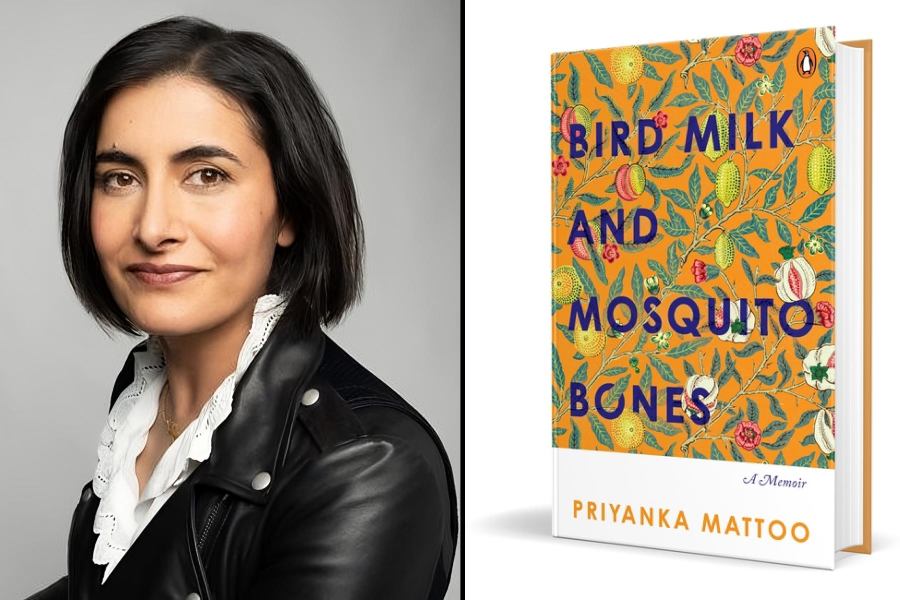

The search for home and belongingness turned filmmaker and podcaster Priyanka Mattoo into an author. The Kashmir-born, who faced displacement in 1989, moved to several countries, including Saudi Arabia and the UK, and finally settled in the US, experiencing multiple cultures, yet longing for a land she can call “home”. In her debut book, Bird Milk and Mosquito Bones, Mattoo, who has been a contributor to New York’s leading dailies and who has directed and produced short films like The Polka King and The Homestay, pours her heart into the book that was emotionally challenging for her. A tete-a-tete with the author before the book hits the stands on June 18.

The title Bird Milk and Mosquito Bones is whimsical.

I’m so glad it stands out. I had originally thought the book would be a series of lighthearted essays about food and family, but turned into something so much more complex than that in the writing. When I had a finished manuscript, I had no title, but I knew I wanted something evocative of my culture; something that would punch people in the face. I remembered an old Kashmiri phrase that I had come across: “Chhari daud t’e meh’i adij.” It refers to treasures so precious and delicate that they might well be imaginary. It reminded me of the home we had built in Kashmir, and was obviously and immediately the new title.

Was Kashmir and your childhood experience in India the inspiration behind the memoir?

I remember reading a Kashmiri news item a few years back, and realising that while there is so much reported about things that have happened to us historically and politically, I hadn’t read an account delving into who we are as a contemporary, living, breathing people — celebrating our culture, our heritage, sense of humour, food, and survivalist spirit. So I suppose I ended up writing the book I wanted to read.

Could you give us an overview of the main themes explored in your book?

The big theme is whether you can ever really attain the feeling of home once yours has been left behind. Another is shedding family obligations, both romantic and professional, to pursue my own kind of family and my own creative path. There’s a nod to the family we choose, the friends we surround ourselves with when our own family is far away. There are essays about the intersection of art and commerce. And, of course, the book also has a throughline of food as a language of love.

Which address finally made you pick up the pen and share your story?

This final one in Los Angeles, now that I’m settled with a job, husband and kids. For a long time it all felt too unwieldy to talk about, but maybe I’ve finally found the stillness that allows me to reflect on a complex life.

Humour has been part of your filmmaking craft and your book has been appreciated for being funny. How different is adding humour to a film’s script vis-a-vis a book?

The humour in a script I write can be situational, like a silly scrape I get my characters into that’s always fun, or in a turn of dialogue, whether it’s banter between a pair of lovers, or family members teasing each other. In the book I suppose the humour is more observational; direct quotes from my parents, who I think are hilarious, but also maybe the way I notice things. I don’t necessarily think of my observations as outright funny, but I hope to surprise and delight the reader with new ways of looking at our shared experiences.

How did you go about researching for the book, especially about the folklore and cultural references?

I did read a lot of books. Many histories of Kashmir during the British Raj, poetry, rundowns of Hindi films et cetera. I also experienced a lot of art, sought out interesting people, and tried to weave in the things I was being affected by as I read it. You’ll get a strong sense of what I was reading, hearing, and cooking as I read the book. The human research included endless interviews of family members and friends. It was a lot of fun to be able to interrogate them about their memories and feelings.

In what ways do you think your book contributes to our understanding of the cultural heritage and traditions you’ve explored?

It was really important to me to present a full picture of a Kashmiri family, outside of the news. I hope that in introducing the reader to my clan, the term “Kashmiri” doesn’t evoke what we’ve lost, but who we are, were, and what we carry forth, even scattered across the globe.

After moving out of your birthplace, was there a place that made you feel it was home?

I still feel so comfortable in London, and I can’t quite explain it. Maybe because I was so young there, and all the comfort I felt as a child can still be accessed when I go back. I came to the US as a teenager and became a citizen as an adult, so while it’s definitely my home, I don’t have that childlike sense about it.

Do you still go to Kashmir or have you visited Kashmir while writing the book?

I haven’t been to Kashmir since 1989. At this point it’s not because I’m physically unable, but I’m still somehow not emotionally prepared. A part of me wants to hold it in my mind like a snow globe. The other part of me knows I will have to take my family, so they can see where I’m from.

Were there any challenges you faced while writing the book?

It was emotionally much more difficult than I thought. I hadn’t been able to comprehend how challenging and exhausting it would actually be to relive the hardest parts of my life for a month at a time, while I wrote about certain things. But as the material lightened, so did my mood, and having processed all of it makes me feel so much lighter now that the book is done. It’s like two straight years of all-day therapy.

Do you intend to convert this into a film or series?

While I don’t intend to do a direct adaptation of the book, fictionalised storylines from my life do find their way into my work. I’m currently writing a pilot for CBS about a woman on the precipice of pulling away from her family to make her own life choices, as I did, and a feature film based on my short film The Homestay, which was also inspired by a family story, and which is about an older couple who are soulmates but won’t admit it, which is how I jokingly refer to my parents.