The news of Gita’s passing on September 16 threw me off balance. She was 80, and had been ailing. She lived a full life. The daughter of the legendary political leader of Odisha, Biju Patnaik, Gita leaves behind her younger brother Naveen Patnaik, the chief minister of that state, and her son Aditya Singh Mehta.

I’ve known the acclaimed novelist Gita Mehta and her husband, Sonny Mehta, for almost 30 years, when I first interviewed her for The Straits Times in Singapore in July 1995. The Mehtas lived in New York, where Sonny worked as president and editor-in-chief of the giant Knopf Publishing Group, and I interviewed her a few times thereafter. She was sharp, exuded a brilliant wit and wowed literati and glitterati with her thousand-watt smile that turned heads when she walked through the door.

Last year, on November 29, I sent her a frantic email to ask how she was. “I have been looking desperately to connect with you ever since Sonny’s death in Manhattan in 2019. Hope you are well and coping with a separation that truly is unimaginable.” I also left voice messages after his passing.

Gita replied on December 11. “Dear Julie, I’m sorry I didn’t get your earlier emails otherwise I would have replied at once. Actually, I had a stroke 3 months ago and have been immobilised and out of circulation. Yes, I do miss Sonny very badly especially now that I am about to turn 100 years old. Everyone in New York misses Sonny badly as well. He seemed to be a lighthouse for his trade in spite of his own ill health.”

I immediately wrote back, informing her of the publication of my article in The Telegraph t2 just a few days earlier on her novel A River Sutra turning 30 years old.

Gita and I were in close touch when I was completing my PhD dissertation on her A River Sutra at the University of Toronto and later when I was teaching there. The author of the classic Karma Cola, published in 1979, leaves behind her trademark fizz. Besides this book and A River Sutra, she has other bestselling works, such as Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of Modern India, Eternal Ganesha: From Birth to Rebirth, and Raj. She produced and directed at least 14 television documentaries for UK, European and US networks. She was also a television journalist for the US television network NBC. Gita studied in India before moving to the University of Cambridge in the UK, where she met her future husband, Sonny.

She was back in the news in January 2019, when the government of India awarded her a Padma Shri in the field of literature and education, which she declined saying it may be misconstrued due to the timing of the award as it had come just before the general election.

I remember her in her signature chiffon saris, a single string of pearls and her sparkling repartee and throaty laugh resonating through the Tanglin Club in Singapore where we met for dinner. Readers and publishers globally acknowledge her significant contribution as an author who brings the complexity and felicity of a prodigious civilisation that is India to the world in both her fiction and non-fiction writings.

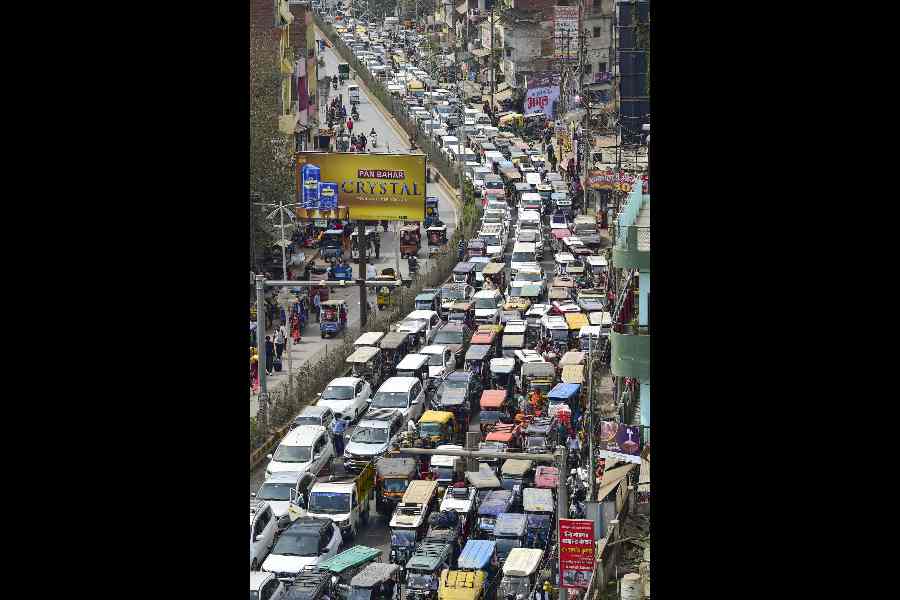

Her view of India is clarified in her thoughts. Sometime ago, in an interview with me, she said: “India is a place where worlds collide constantly: Satellites are launched in space and bullock carts trundle on in village tracks simultaneously. We were Hindus, and grew up serving sherbet to young Muslim men carrying the taazia for the Prophet Mohammad during Muharram. My mother was Kashmiri and read the Bhagvad Gita to us in Persian. I married a Sikh and live between three continents and speak several languages. Dr B.R. Ambedkar, ‘an untouchable’, wrote the Constitution of India and yet you see how shockingly ‘untouchables’ are treated in India…. Women are satis and women are Goddesses in India. The holy shrine of Babri Masjid and Ram Janam Bhoomi are located at the same spot in Ayodhya.... This is India.”

Git’s condition is symptomatic of most Indian writers who write in English. Gita said, “English is a sacred possession. It is a lingua franca in the literature world and has become the magic mantra to knowledge, because armed with the skill to that knowledge comes the means to empowerment and the ability to retrieve our identities and embellish their language in our own unique manner.” In this way, she echoed the African writer Chinua Achebe’s thoughts: “Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English, for we intend to do unheard things with it.”

I remember her words of advice to aspiring writers, so clearly, like the tinkling fall of the Narmada in Amarkantak: “Simplicity. Make the most complex mythology appear in the most profane of settings. It is what R.K. Narayan once told me — just tell the story. Straight. The allure of clarity in the narrative, as you use the English language without embellishments, will make for a charm of your own.”

Thus, I learnt that unlike many of her contemporaries, Gita wrote English, pared of frills. Gita’s books have been translated into 21 languages and been on bestseller lists in Europe, the US and India. Her fiction and non-fiction focus exclusively on India — its culture and history — and on the Western perception of it. Her works reflect the insight gained through her journalistic and political background.

“Look at the Ayodhya issue. I feel like saying, ‘I own that soil too’ when they kill themselves over temple and mosque,” she said. “Rabindranath Tagore called it ‘sacred geography’. It’s a sorry comment on our heritage when the very seduction of our civilisation, which is the massive philosophical leaps of imagination we took at any point in time of our history, has got lost in the politicising of religion,” stated Mehta with a hint of sadness. A lesson we might be wise to remember for the new generation who will take over the governance of a vastly diverse, fractured, and formidable nation.

When asked about where she sourced her stories in A River Sutra, Gita said: “I read the autobiography of the Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa. At one point he had to make 20 films a year to survive. There is an image in his book about how he used to close his eyes to recollect his earliest impressions. That stuck with me. I literally closed my eyes and tried to recall my earliest memories, stories my aunts and mother used to recount about the Hindu myths; incidents that occurred with people I knew when I was young, strange stories I heard from friends. And they unfolded in front of me.”

Gita most succinctly conceded how inspirational myths have invigorated her as a writer:“Myths are extremely powerful tools and can convey a whole range of meanings.”

She signposts the inextricable ties that bind different religions with India’s complex history by employing and reinventing the memory and language of the 16th Century mystics, and representing them in diverse forms, in every story in the novel:

Some seek God in Mecca,

Some seek God in Benares.

Each ends his own path and the focus

of his worship.

Some worship him in Mecca.

Some in Benares.

But I centre my worship on the eyebrow

of my beloved.

— Imrat, singing a hymn by the mystic Sufi saint Kabir

May your literary works fizz forever, dear Gita.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College