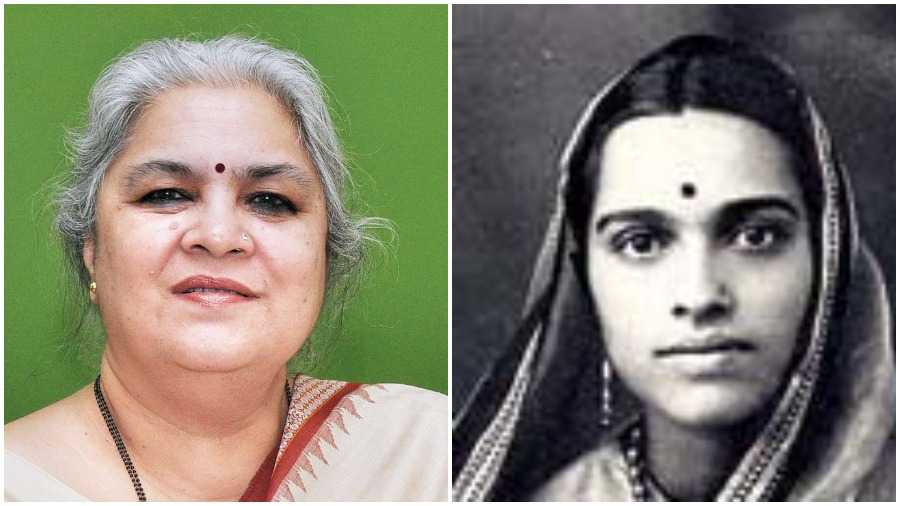

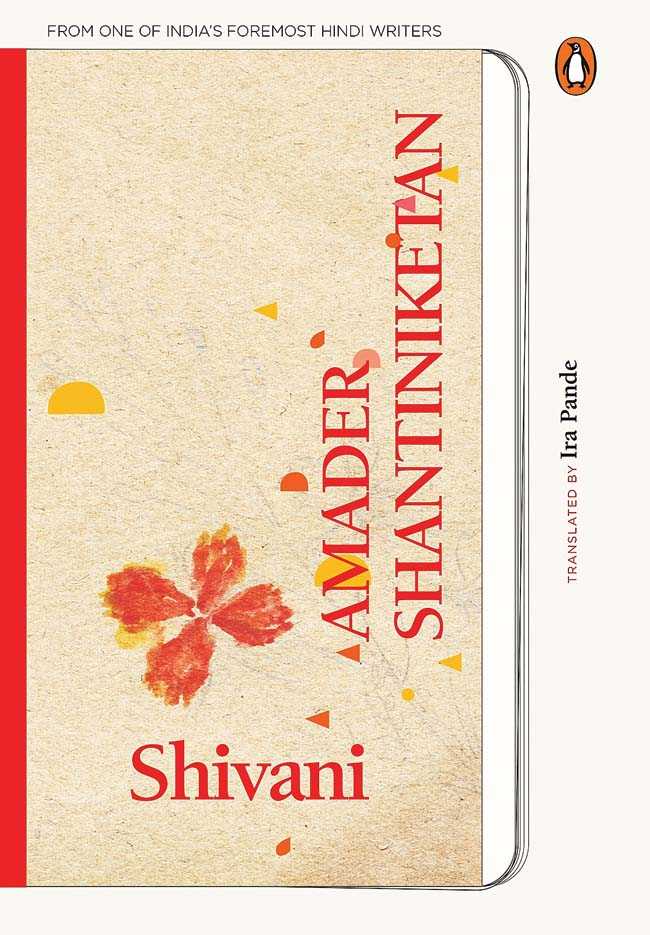

There is a heart-warming lighting up of eyes of the alumni of Pathabhavan, the school section of Rabindranath Tagore’s ashram in Shantiniketan, at the mention of their beloved school. India’s foremost Hindi writer Gaura Pant ‘Shivani’ spent nine glorious years there as a student. Recounting her experiences there in an effort to commemorate her time and associations built, she penned her thoughts in a small book aptly named Amader Shantiniketan. The late author had time and again attributed her creative voice and its growth to the learnings at Gurudev’s ashram and perhaps felt the impact her teachers had on her oeuvre throughout her life time. The book by the Padma Shri awardee, that was published by New Age Publishers in Calcutta sometime in 1960s, has now been translated by her daughter Ira Pande and published by Penguin India. Amader Shantiniketan by Shivani, translated by Ira Pande (Vintage; Rs 499) is a book that has beautifully retained the charm and brevity of the original text.

Pande is the former chief editor of the India International Centre’s Publication Division and the winner of a Sahitya Akademi award for her translation of Manohar Shyam Joshi’s T’ta Professor. Filled with joyous moments captured in the eyes of a young girl, this is a wonderfully nostalgic trip waiting to be taken –– even for those who haven’t had the great fortune of studying in this hallowed institution. We spoke to Ira Pande about her experience of translating her own mother’s words. Excerpts…

Having translated other works, how was the experience of translating your own mother’s words different?

Delightful, as this was the first time I heard her voice as a child and young girl. Her fiction and other works are all in an adult voice, so it was enchanting to hear her innocent and artless voice in this book.

What is your personal relationship with Shantiniketan, having experienced it through your mother?

Sadly, I myself have never visited Shantiniketan but since my mother and her older sister, Jayanti, were a very large part of our growing-up years, all of us children were exposed generously to the Shantiniketan experience. Apart from the delightful reminiscences they had to narrate, they were inspired by the teachers there to open up young minds in the way that has enriched all of us. I think that a large part of our imagination was stimulated by them and perhaps this is why my sister Mrinal, my cousin Pushpesh Pant and I have always loved telling stories.

As a teacher yourself, how do you think teaching has evolved over the years, especially now with the pandemic doing irreversible changes to our learning and teaching styles?

One of the main reasons I decided to translate this book now, even though it was first written more than half a century ago, was the pathetic state of our primary and secondary education. The failure of successive governments to focus on these vital segments have destroyed generations of learners and made them into parrots who learn by rote. The burden of performing at exams, the crowded classrooms and the over-emphasis on English have denied the full flowering of so many children’s childhood.

The language of the book is so immersive. What are the choices you had to make as a translator to keep the experience so, while also maintaining the brevity of the novel?

I worked very hard to preserve the child’s voice and keep the language of the book as simple and accessible as I could. This is not easy but in order to remain faithful to the sense of wonder and honesty that gives the book its special flavour, it could be no other way. Also, I had to make sure that it did not become a worshipful, cloying hagiographic tribute to her gurus, especially Tagore. That would be betraying the ambience of Shantiniketan.

Do you have an ideal reader in mind when you think of Amader Shantiniketan?

I think a book like this appeals for different reasons to different age groups and social groups. In any case, these were my mother’s words, not mine. I merely transcribed them in another language. She always wrote for the common reader and that is possibly why she was so popular.

How would you assess the translation landscape in India over the past decade? What are some measures that are yet to be taken?

I am happy that Indian publishers are at last waking up to the huge potential of translations from other Indian languages and are not obsessed with English writing alone. We often forget that we have read almost all of European and Latin American writing in translation and how that has enriched the world. There is an enormous treasure waiting for good translators to mine and I hope the readers both here and abroad can be acquainted with it.

What can we expect next from your table?

My mother’s centenary falls in 2023. I am hoping to bring together a selection of her travelogues, essays and portraits for that.