In the eyes of the law, rights cannot exist without responsibilities. But does the absence of legal rights also absolve a person of moral responsibilities? This is the dilemma that propels the plot of Aravind Adiga’s new novel, Amnesty. His protagonist, Danny aka Dhananjaya Rajaratnam, is an illegal immigrant in Australia, a country that banishes hordes of asylum seekers to languish in inhuman conditions in offshore detention centres. However, even a life spent without rights and trying to be invisible seems better to Danny than the life he had as a Tamil Hindu in Sri Lanka, where he was tortured as a suspected member of the LTTE. So Danny works hard to blend in — “[m]imicking a man with an Australian spine, wearing shorts in public... he had kept himself... immaculately groomed”, “Never say[ing] receipt with the P. Be[ing] generous with I reckon”. He also makes himself indispensable to the genteel Australian, by becoming the “Legendary Cleaner” who helps shiny Sydney stay spotlessly clean.

But after four years in the background, Danny suddenly finds himself in the spotlight when one of his clients is murdered and he has a sneaking suspicion about who the murderer is. Telling the law what he knows about the murder would also mean shedding his cloak of invisibility and telling the law about himself that could end with Danny being sent to those detention camps that people “eat nails, and drink things, and cut their wrists to get out of”. Over the next eleven tense hours, Danny criss-crosses Sydney, running from the killer — who he foolishly alerts about his knowledge — as well as his conscience that keeps urging him to speak up. Having thus established the stakes, Amnesty — like its protagonist — is paralysed by indecision about whether to push Danny towards a Hitchcockian confrontation with the killer or inwards into a conflict with himself. What emerges is an introspective novel about the state of illegal immigrants everywhere in which the unsolved crime becomes not only incidental, but also distracting.

Adiga unwisely burdens himself with the timestamped format: instead of creating tension as intended, the hourly accounting of Danny’s day edges on the perfunctory and inane. Eleven hours is too little time for all that Danny does, forcing Adiga to condense activities into unrealistic time frames — for instance, Danny vacuums an entire apartment, including toilets, does the dishes as well as rearranges the furniture in just 19 minutes. Is he a ‘legendary’ cleaner or one with superpowers? The novel is also littered with two-dimensional characters that the author creates only to exploit them as stereotypes. Yet, Adiga must be commended for his skilled tonal variations for each character and the crispness of the dialogues. But all the unnecessary paraphernalia shifts the focus of the readers from the powerful moral questions posed by Amnesty and the insightful sociological observations that emerge from it.

Some of the best sections of the novel are those in which Adiga explores what Foucault had described as the pyramid of subordination: local Australians loathe all immigrants; legal migrants hate illegal ones; illegal migrants despise the idea of more illegal migrants coming in to stretch already meagre resources. The author avoids both sentimentality and political correctness while underlining the power dynamics that govern these social hierarchies — “White people. Obsessed with Muslims. Because they’re frightened of them.” Adiga shows that only those at the top of this power pyramid are entitled to tell their own story and actually be given a fair hearing. Each time powerless Danny recounts his story, he relinquishes control of his fate, making himself vulnerable and risking his invisible existence. Danny’s story — like that of all those without power — also becomes a source of entertainment for others, his clients, his girlfriend, his former neighbour: “Torture? Our Danny? Oh, tell me again.” The amnesty that Danny dreams of is the only thing that can bring him freedom, both from humiliation and the control of others.

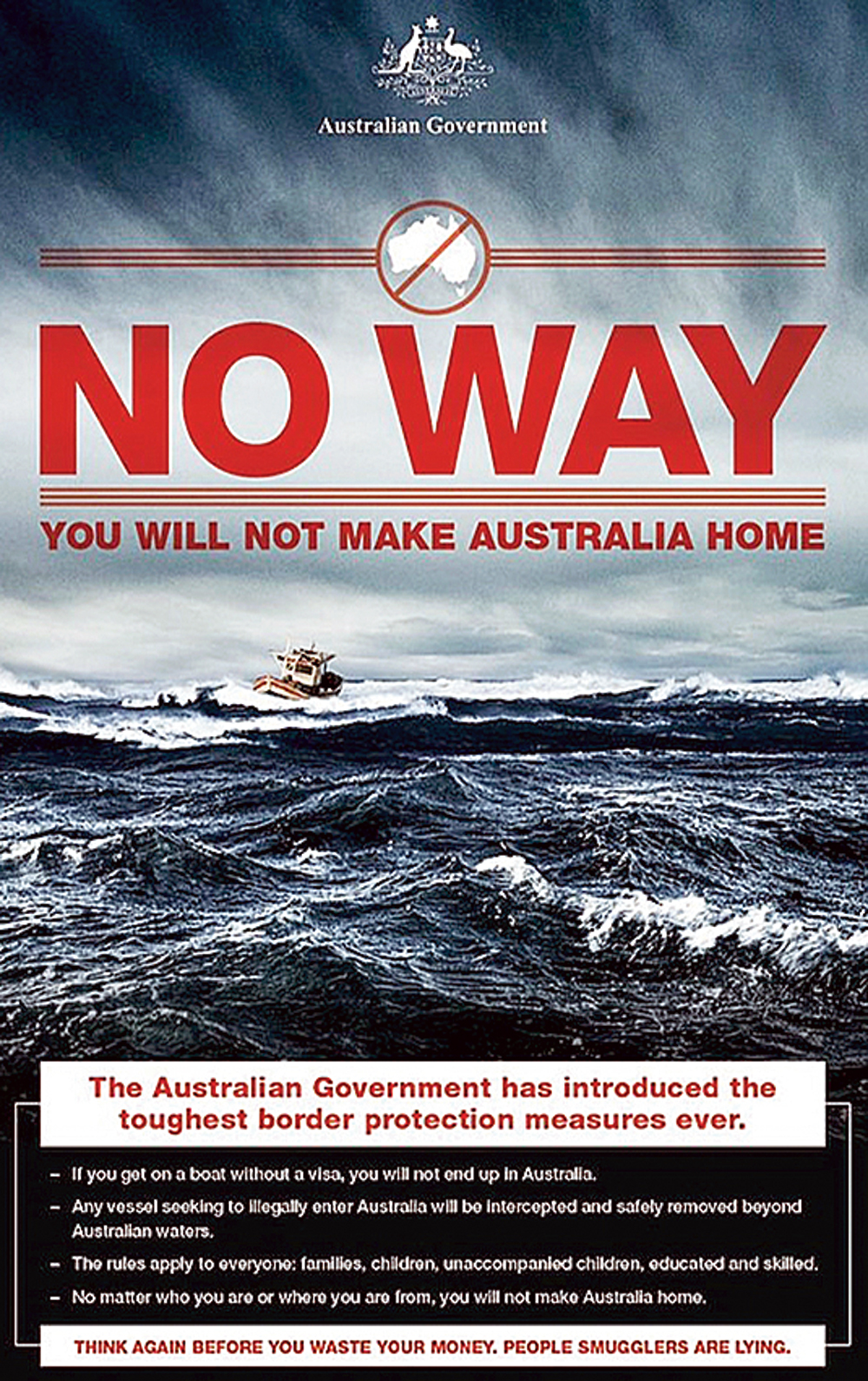

But what makes Amnesty a significant book is Adiga’s scathing indictment of Australia’s hypocrisies. Immigration props up the economy with “rip off” colleges luring foreign students who pay exorbitant amounts in the slim hope of a post-qualification job and visa; with farmers filling their fields and orchards with undocumented workers and calling immigration when wages are due; with lawyers, accountants and other upstanding members of the community looking the other way while their homes are cleaned on the cheap by illegal immigrants. Yet, immigrants are subjected to the most draconian laws and human rights violations. The author excels in his dissection of the neoimperial divide-and-conquer strategy that is used against immigrants. The State recognizes that none will guard nationality more zealously than the naturalized immigrant who is ever-eager to set himself apart from his paperless peers. Indeed, while white Australians pay scant attention to Danny, it is Southeast Asian immigrants like himself who keep threatening to report him to the authorities.

Equally important is Adiga’s contemplation on the ‘fairness’ of law and how it is bent to suit the needs of the powerful. For Danny, “[t]he law was a magic circle, and inside its protection, Australians... slept like children... In Dubai the law let employers cheat you out of your wages. In Sri Lanka the law was a burning cigarette on your forearm.” To engage with the law is to put oneself at its unproven mercy. In the end, Danny is left with little choice but to put his trust in a flawed system. As the novel hurtles towards the inevitable, readers are left pondering whether morality, like law, is a concept invented by those in power.

Amnesty by Aravind Adiga, Picador, Rs 699