The prose in the climax of The Black Tower - one of the murder mysteries featuring the detective, Adam Dalgliesh, a creation of the August-born author, P.D. James - may seem a touch too poetic. The cadence of the prose makes it difficult for the reader to even understand whether it is Dalgliesh or his armed adversary who triumphs after a bout of mortal combat on a precipice. Poetry, evidently, eluded James's literary grasp. It would not be wrong to speculate that Dalgliesh's poems - the detective has several volumes of published work to his credit - could have been mundane as well. Yet, poetry is central to Dalgliesh's sense of balance. For it helps him cope with a loss like no other: the death of his wife.

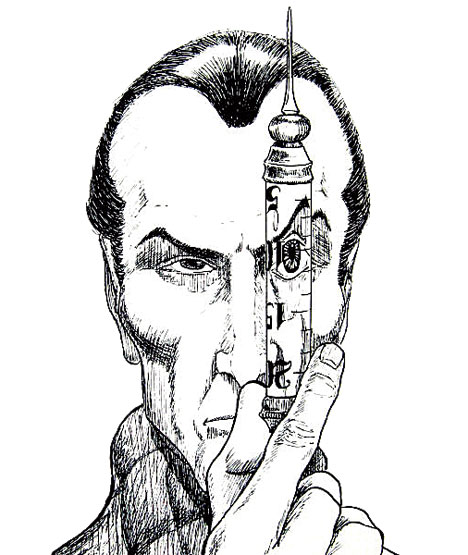

Some of Dalgliesh's peers have, over the years, made more malignant choices when it comes to getting through the life of a sleuth. Sherlock Holmes dabbled with cocaine. Interestingly, screen adaptations of this beloved detective have tweaked a few things - Watson, for example, is a woman in the television series, Elementary. But Sherlock's love for crack has not been tinkered with.

The genteel kind of detectives have their share of follies too. In the early works, Miss Marple is quite a prattler, a far cry from her quiet, matronly, seemingly benign self that we encounter in Agatha Christie's later books. Closer home, Feluda's circle of life is completed only by crime and the companionship of a cousin and a writer-friend. He is, inexplicably, asexual, never accommodating a woman as foe or friend. He isn't gay either.

Byomkesh - unlike most of his ilk - marries; but conjugal domesticity was perhaps Saradindu Bandopadhyay's way of easing Byomkesh into a life of contented retirement. Yet, 16 years later, Byomkesh returns, son and wife in tow; Satyabati cannot, evidently, keep Byomkesh's luminous mind from being drawn to the shadowy world of crime.

But eccentricity or deviance can be more than a coping mechanism for the investigator. It is emblematic of the distance that separates the detective from the trap of conformity. For the detective is the resident of a twilight world: he is both the upholder of law and convention as well as their ardent challenger. Consider Hercule Poirot's fetish for toiletries. Is it not a delightful way of subverting the tradition that seamlessly fuses cerebral intelligence with masculinity? A detective's uncovering of the hollowness of some of society's honoured codes of behaviour and institutions makes him a potent agent of chaos. Like all untamed creatures, he must thus allow himself to be lulled occasionally - by drugs or other unsavoury diversions - to accept an uneasy truce with convention.

Coke, the stuff that Sherlock is vulnerable to, is not without its uses.