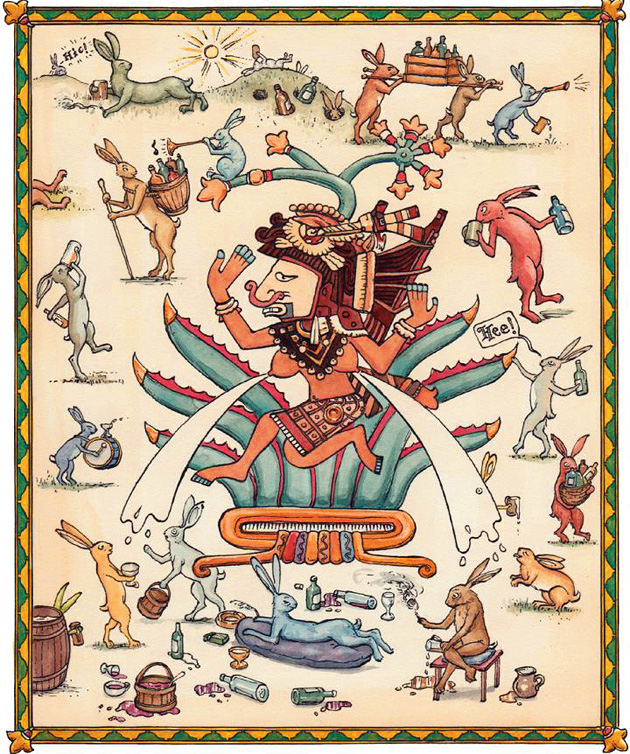

A reader with an abstemious bent of mind must pick Mark Forsyth’s latest book with caution. A Short History of Drunkenness is, by all means, a book of excesses. As a serious academic discipline, history has got itself into multiple problematic binds in the last fifty years or so: micro-histories, meta-histories, the veracity of anecdotes or archival research, you name it. The reader will rarely know Forsyth’s sources, but will be catapulted through a good ten thousand years of the story of the human race, steeped in tipple, and the author will call it ‘history’. He also calls it ‘short’. He also makes it clear that the book is not about the nature of spirit, but about the spirit of nature: “It’s not about alcohol... it’s about drunkenness: its pitfalls and its gods. From Ninkasi, the Sumerian Goddess of beer, to the 400 drunken rabbits of Mexico.” The sustained hyperbole of the narrative with a rare disdain for notes or references (there is a bibliography, however, at the end of the volume), scant regard for reasoned analysis, and a penchant for making claims that begin with “I don’t know... but I suppose...” or “I should probably spout some guff here about...” may not be the ideal reference book for the student of history, but is a treat for the connoisseur who enjoys a robust anecdote from the past with his drink.

There is a narrative discipline, which begins about three thousand years ago in the Sumerian bars and ends in the present day. The book journeys across the globe, talks about various kinds of alcohol and the philosophical dispositions of the people that drink them, often attempts a perfunctory cultural analysis, refers to socio-economic and ethico-legal tracts and draws conclusions such as: “And so in about 9000 BC, we invented farming because we wanted to get drunk on a regular basis.” In all seriousness, the discerning reader will know that Forsyth is telling us a good story, and he also wants to make us laugh. It may sometimes get tedious, the joke over-the-top, but the book never loses its sunniness of spirit.

Often enough, Forsyth draws upon the animal kingdom to insist that the human is not the only species that is fond of the tipple. In the “Evolution” chapter he talks about the rat colonies where the King Rat is a teetotaller, while all other rats get together at the slightest whiff of alcohol. Forsyth concludes: “Alcohol consumption is highest among males with the lowest social status... they drink to forget their worries... they drink... because they’re failures.”

From Egypt to the Greek symposium, the Bible to ancient China, from the Wild West to pre-revolution Russia, Forsyth discovers drunkenness to be the backbone of the history of human civilization. In the chapter on the Greeks he borrows from Plato: “Self-control, said Plato, was like bravery. A man can only display bravery when he’s in danger. A man can only display self-control when he’s drunk a lot of wine.” While referring to the first miracle performed by Jesus in Cana, where he transformed water into wine, Forsyth reminds his readers: “Jesus started his career in a shower of booze... He’s at a wedding reception and they run out of plonk.” He concludes the chapter on the Bible rather perceptively: “Christianity can never be totally teetotal. The Last Supper saw to that.” The irreverence is infectious and the reader, once he catches on to this tone of levity, leaves history aside and concentrates on the humour. One turns to such a book, chatty as it is, on a lonely evening, and dips into a barrel of laughs.

An image of Doctor Syntax making free of the cellar extracted from page 143 of The Tour of Doctor Syntax: in search of the picturesque. Wikimedia Commons

A Short History of Drunkenness By Mark Forsyth, Viking, Rs 699