When the German printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg, designed his first letters for print, he envisioned the typeface as an instrument of communication. Little did he know that in time — only a few hundred years — a fellow German would wield a typeface as a weapon of division. In January 1941, Adolf Hitler banned the use of Fraktur — one of the several Blackletter typefaces — condemning it as Judenlettern (Jew-letter) and replaced it with Antiqua, a typeface in the Latin script. The ban on Fraktur was rich in irony; only a few years back, the Führer had himself used a version of the Fraktur typeface on the cover of his autobiography. The fate of the Fraktur changed in the wink of an eye — from the official font to an outlawed one.

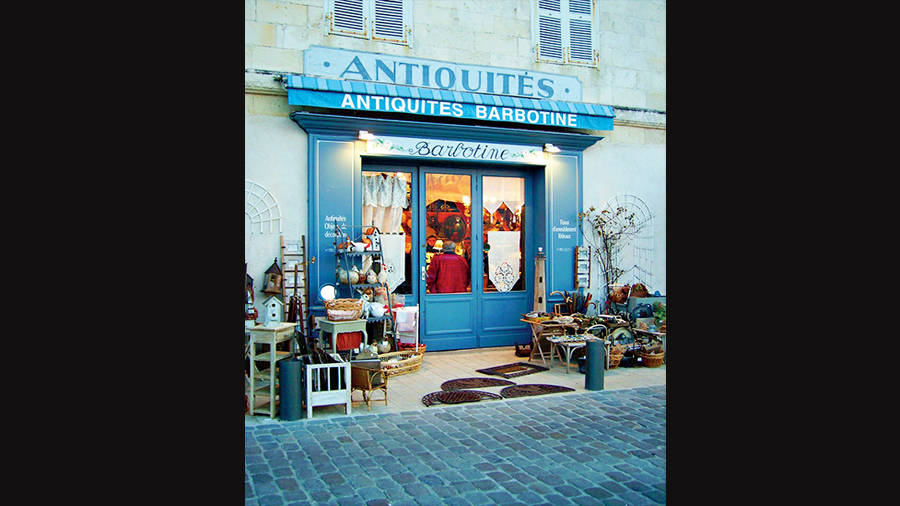

History, however, shows that typefaces are not merely tools of division: they have also displayed the power of consolidation. In the Basque Country in Spain — known for its fiercely independent identity — the Basque lettering serves as a cultural standard, appearing on almost every storefront and street sign. On the other side of Europe, in the Balkans, fractured not only by borders but also by scripts — Croatia prefers Latin while Serbia swears by Cyrillic — it fell upon a hybrid typeface, the Balkan Sans, designed by combining the two scripts, to unify the two hostile cultures.

Advertising agencies, much like politicians, have discovered the potential of typefaces to influence public opinion — leading brands often design their own fonts to subliminally manipulate the consumer to buy their products. Helvetica, for instance, appears in a myriad business logos, ranging from those of automotive firms to food-processing companies. The innocuous design of this typeface, it is argued, makes the promotional tone less conspicuous, surreptitiously bringing the product closer to the consumer. Helvetica, a critic observed, “has long been used to obfuscate corrupt corporate messages”.

This deceptive facet of typefaces was explored in a survey by The New York Times, which showed that respondents considered statements typed out in Baskerville to be more credible than those in Georgia, Trebuchet and, most certainly, Comic Sans. That this did not dissuade CERN from announcing a historic scientific achievement — the confirmation of the Higgs-Boson — in the dreaded font is a wonder.

Political leaders are known to choose particular letterforms for campaign posters based on their visual impact on their target voters. Does the use of typefaces to manipulate perception further erode the sanctity of the printed word? This is not a redundant query in the age of Post-Truth.