Book: The Song Of The Cell: An Exploration Of Medicine And The New Human

Author: Siddhartha Mukherjee

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: ₹799

Siddhartha Mukherjee made his reputation as a science communicator with The Emperor of All Maladies and The Gene, about the quest for cancer cures and the language of life, respectively. Scientific quest stories are generally fascinating. Andy Weir’s The Martian was a hit because its backbone is the science it takes to stay alive on Mars and be rescued. In non-fiction, Gene Machine, by the chemistry Nobel laureate, Venki Ramakrishnan, is about a tiny band of obscure scientists doing nothing but X-ray crystallography; and, yet, it’s as gripping as Murder on the Orient Express.

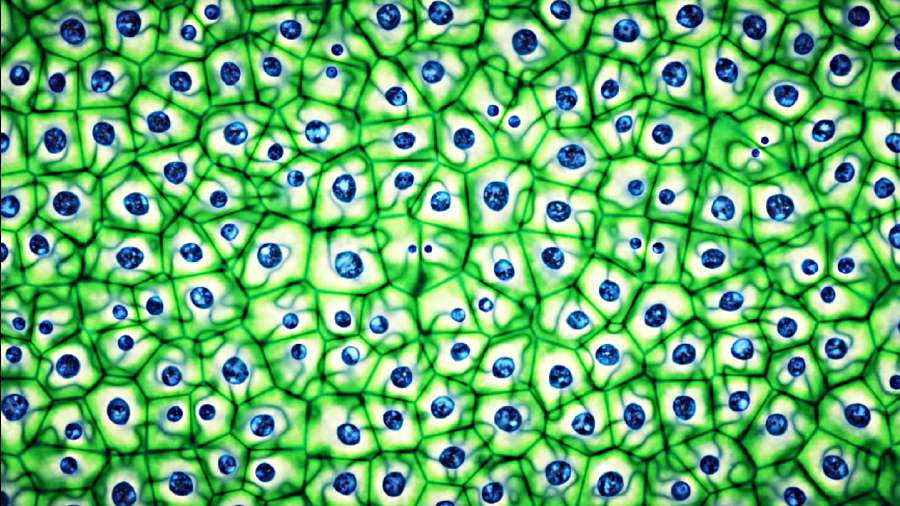

Mukherjee departs from the tradition in The Song of the Cell. It isn’t a quest but a history of the life sciences, told through a huge cast of theorists, experimenters, clinicians, patients, poets, dreamers and cranks, starting with pioneering microscopists like Robert Hooke, who first saw plant cells, and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who saw mobile ‘animalcules’ through his lens.

The history of science is a jagged curve because hypotheses must be tested in the lab which, quite often, is not up to speed. Mukherjee points out that John Dalton’s atomic theory had to wait about a century for Niels Bohr and Paul Dirac to take its measure. The wait was actually much longer because atomism, the parent of atomic theory, is as old as Jainism and the Nyaya-Vaisesika school of philosophy. In the history of medicine, anatomy was pioneered by dissectors like Leonardo da Vinci (who gets surprisingly little attention here) and Andreas Vesalius in the 16th century. Mukherjee dwells on this driven man who looted the gibbets of Paris, having understood that his professors were ignorant because they were too snooty to touch a cadaver. However, physiology and biochemistry, the bedrock disciplines of the life sciences, would not be ready to add meaning to anatomy for centuries. As late as the Eighties, Gray’s Anatomy was about three times the size of the biochemistry texts used by pre-clinical MBBS students. Its bulk owed much to advances in cytology, the subject of Mukherjee’s book.

A classic case of laboratory lag concerns the Hungarian obstetrician, Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), the pioneer of antiseptic procedures who eliminated the European scourge of childbed fever, and who was hounded by his peers until he lost his career and perhaps his sanity and his life in an asylum.

Mukherjee recounts that Semmelweis worked in an obstetric clinic in Vienna General Hospital where childbed fever, resulting from infection and sepsis, was rampant among new mothers. But it was rare in another clinic run solely by midwives. The difference, he observed, was that doctors shuttled among obstetrics, autopsies and dissection, while midwives had no contact with cadavers. Ergo, cadavers were the source of disease, and it was carried by unclean doctors. Semmelweis told them to wash their hands, and was angrily dismissed as a crank. Years after his death — ironically, from sepsis after a beating by asylum guards — Semmelweis’s theory was vindicated in the laboratories of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, where the germ theory of disease was formalised.

The book first traces the medical equivalent of atomic theory — the realisation that the seat of disease is not gross organs or tissues, but the cells which constitute them. It looks ahead to interventions like cell therapy and reminds us that it is not a novelty — blood transfusion dates back to World War I. Mukherjee is not an optimistic futurist, though. He alludes to free neurons self-organising into ‘mini-brains’ with some scepticism.

Indeed, human development remains largely mysterious, especially that of the central nervous system. What tells a cell that its descendants will be part of the vagus nerve, the sartorius muscle or the omentum? Mukherjee calls it “a virtuoso act, an elaborate, multipart symphony perfected by millions of years of evolution”, but even now, we can hear only part of the score. Ernst Haeckel’s captivating formulation, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” — implying that in its development an embryo passes through all the stages of the evolutionary history of its species — has also fallen from favour. So, what do we know?

Mukherjee’s most sobering chapter was written during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is prefaced by a passage from Boccacio’s Decameron, the fruit of the plague years in Italy. Almost seven centuries later, Covid-19 was a deadly rebuke to the human race, which rashly believes that science has made it invincible. Ironically, our pets were vaccinated against coronaviruses but not ourselves. And when the pandemic struck, as the outgoing WHO chief scientist, Soumya Swaminathan, now says, WHO bungled its response. Mukherjee writes that the pandemic was a lesson both in epidemiology and epistemology. Which brings us to another truth about knowledge that Mukherjee does not go into: industry follows the money. The “new human” that he writes about, with its human errors artificially corrected, is being moulded by market forces, not human needs.