WHY WE DIE: THE NEW SCIENCE OF AGEING AND THE QUEST FOR IMMORTALITY

By Venki Ramakrishnan

Hodder & Stoughton, Rs 699

It is a great leveller. A friend, aghast at the sudden passing away of his young uncle, spent years in orchestrated agony as he ensured older folks, at bedtime after lights-out, practised the lifegiving callisthenics of breathing.

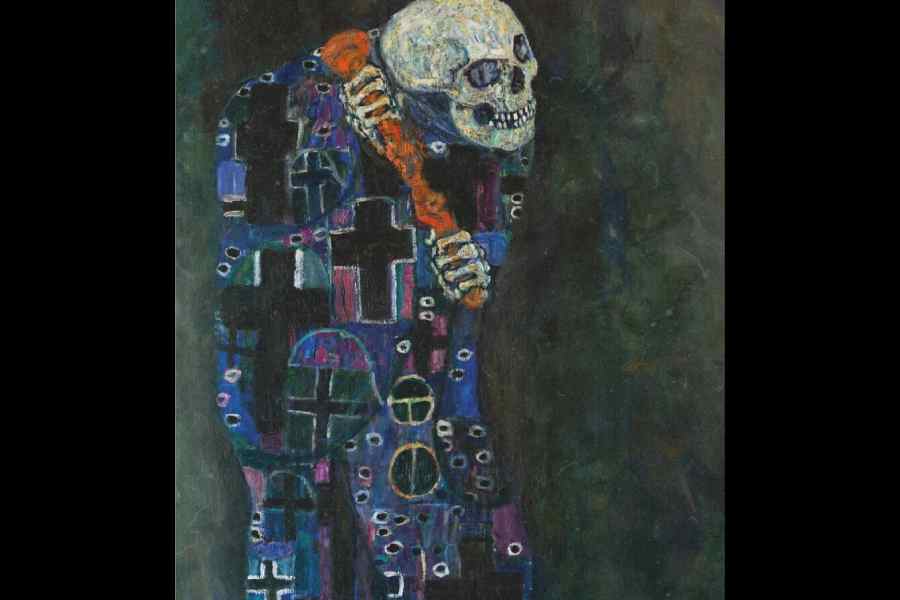

Death is a constant watchword, the arbiter of our most crucial decisions, the end of the beauteous cul-de-sac of life that we so strive to avoid. In his new book, a Nobel Prize-winner summarises many storied debates surrounding the issue. He brings in scholars and anecdotes and walks to watch wilting flowers to supplement his narration. It is in the morbid nature of death and the incongruity of it that any description of it presupposes a study of life, because life is the observable, tangible side of the same coin, the other side lost to human access.

Prefatorily, the author wards off claims of snake-oil salesmen and quacks claiming to imbue people with longer lives and makes an academic effort to decipher the mysteries of death. The book has few surprises. In its unavoidably limited foray, it provides succinct insights into what has already been unearthed, and that should be enough from what is admirably and clearly a generalist account. Yet, looking at a long line of white-clad ready-reckoners heralding the cutting-edge in science and life, we have come to expect more from our foremost thinkers. Venki Ramakrishnan won the Nobel for his work in intracellular structure. His approach to the book’s subject naturally stems from and threads around it, but this is not always to its strength. A principal fallacy of this brand of books is that they start from first principles and then attempt to do too much, blanching any gleanings from whatever fraction read thus far.

When it works, it is not as a commentary on death itself — which is understood as an inevitable, if sometimes precariously fungible, event. We’re living in an era of alarmism and the antics of Bryan Johnson are not unknown. (He is a tech businessman who has stooped to swapping blood with his son in a quest to live forever. Johnson, 45, claims to “look 30” — nobody’s fooled.) Further, nobody I know wants to live forever; life and its social dimensions are not as yet designed for an average population inching closer to the upper extreme. Doom is an aesthetic zenith. One understands that life and immortality are interesting questions from the experiential dimension, not granular details of bodily components we can do nothing about.

In the play, Copenhagen (Michael Frayn), the central question is, of course, who invented the atomic bomb, something that permeates every bloodied page of the epic. Yet the characters talk about human guilt, the thirst to run away from persecution, the desire to establish themselves, ingratiate, stitch new horizons. In the human stories of the people who worked on the science of living — most of them ineffectual from the scientific angle — a storytelling opportunity Ramakrishnan relishes, the book comes alive. It soars when it touches upon scientists beefing with one another, when it chronicles political escapades amounting to fruitfly-hunting soirees in foreign labs, when scientists who marry each other also parry with each other on matters most abstract and meaningful.

When the American actor, W.C. Fields, couldn’t don his top hat anymore and was spending his dying hours reading the Bible, he was asked why in hell was he doing that. His reply: “I’m looking for loopholes.” Everybody is! From Cormac McCarthy’s protagonists to a random raven who pecks at a hunk of carcass. Every fantasy enterprise begins with a diabolical urge to live forever and, in doing that, the antagonists undo themselves. Yet the tales of hubris and nature’s unredeemable angst at outliers and cheaters are always enjoyable. And they, for a change, do live forever.