Book: A Walk Up the Hill: Living with People and Nature

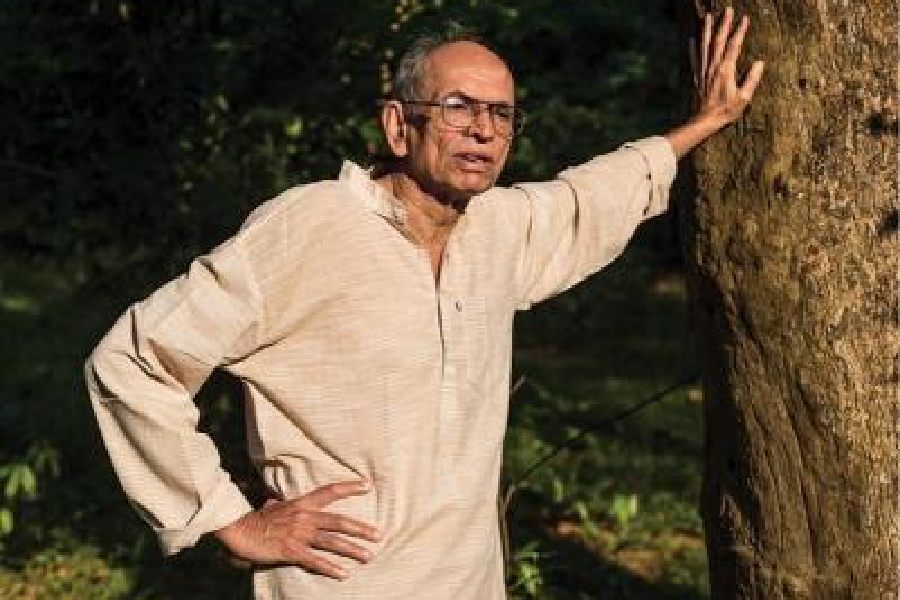

Author: Madhav Gadgil

Publication: Allen Lane

Price: Rs 999

Reading A Walk Up the Hill is like listening to Madhav Gadgil offering glimpses of the ideas that he formed and how; he gathered the wisdom through interactions and scientific investigations. The book is a memoir of a brilliant scholar, teacher, scientist, activist, policy influencer and more. I have met Gadgil only once; he was in Calcutta to deliver a public lecture at Rabindra Sadan. The language of the book is as easy as his spoken words.

The book is divided into 25 chapters. Gadgil’s deep insights into ecology, environment and society spanning eight decades come through from the word go.

Gadgil maintains his outspokenness about Indian society, economy, and governance throughout the book. It is a commentary on the changes in India in general and, occasionally, in other countries and globally, interspersed with personal experiences. He is scathing in his indictment of governmental and non-governmental institutions, politicians and bureaucrats. Sample the following: “By the early sixties, the public-spirited people who had made up a substantial fraction of India’s early political leadership had either retired or been eliminated from any leadership role.” Commenting on a flood episode that swept Pune in 1961, he writes, “… the rulers of the country were following the colonial British policy of disregard for the people of India.” On forest cover estimation by the National Remote Sensing Agency, he writes, “The results of the NRSA study were startlingly at variance with the official information from the Forest Department.” The government, in response to the discrepancy, asked the NRSA to stop such assessments and set up the Forest Survey of India. “The response of a scientifically minded government would have been to assess what the deficiencies were in their own methodology and statistics and set about improving their performance.”

As a faculty at the Indian Institute of Science, Gadgil produced a number of PhD scholars who have gone on to become illustrious teachers, researchers and practitioners in their domain. I think all his scholars find mention in the book; and not once is it out of place.

One of his scholars, now at the zoology department of the West Bengal State University, has been a great influence on my career and me. While I was still a postgraduate student, he not only engaged me in stimulating intellectual discussions but also drew such a compelling imagery of the Sundarbans that I ended up pursuing academic research in the region and have worked there ever since. Even without meeting Gadgil then, I imbibed his wisdom and have tried to put it in practice. I am sure there are scores of others whom Gadgil has deeply influenced. His memoir will continue to inspire the environmentally inclined for generations to come.