Book: BEASTS OF ENGLAND

Author: Adam Biles

Published by: Picador

Price: Rs 599

This book offers a powerful allegory for these times of global crisis marked by economic inequalities, political manoeuvring, and geopolitics that paralyse all that was best conceived in the values of social welfare and egalitarianism, both

by the Right and the Left. It is a fable for our times — generations wearied by

hopelessness and inaction in the face of the mighty State. Democracy and sacred institutions seem flimsy, eventually kindling a docile temperament in individuals — a defeatism looms large.

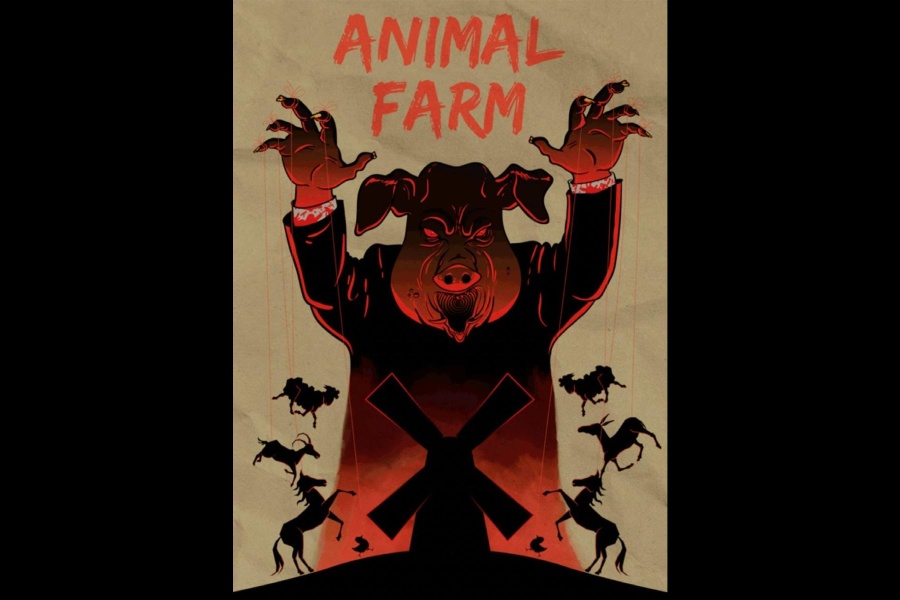

Adam Biles picks up the narration from where George Orwell left off in Animal Farm and, in entirety, complements its structural and metaphorical integrity. Biles has the daunting task of unpacking recent world events with all their dysfunction and sickness, find a suitable canvas, and paint the misery and ennui of attachment

to ideological idealism and exasperation ensuing from vanquished hopes. Events closer to him spatially and temporally are dealt with lucidly.

After the despotic years of Napoleon, the Manor Farm reeled under years of misrule and bad governance and it ended with the establishment of a “Council of Animals”, a representative body that “choozes” its First Beast through a quasi-democratic process. The farm has two ideological factions— Joanists and Animalists. Traction between the two factions resembles superficial policy difference between the liberals and the conservatives in some of today’s Western democracies; just that one sounds pleasant while the other is brazenly regressive. Both, through differing modi operandi, repress people’s (in this case, the Beasts’) right to access fruits of their labour and indoctrinate false ideas about their shrinking lives. Cosmo, the Quartermaster, performs the exact function of a pacifier and mouthpiece of the repressive State, always letting the animals perceive they are better off in comparison to their past generations. Every new regime rewrites the history of the farm, highlighting parts that are commensurate with their narrative while discarding the ones that bear the power to unsettle their falsehoods. Speeches made by the leadership are marked by high emotionality and lack of facts. On reading closely, one finds a world not different from ours, infested with post-truth, jingoism, xenophobia and socio-political unrest. The divisive power is nourished, consolidated, and worked upon by forging State-centric narratives. On the fringes of the farm, a quarry exists where they dump the cast-away history of the farm. It also exists as a safe space for the outcasts — the prosecuted, battered, abused, and exploited — a marginal place that tells the story of oppression.

Just as the annals of our political making and unmaking are riddled with movements and counter-movements, so are the happenings on the farm during

one complete year. The apparent redeemers, reformists and radicals had led the

farm into deeper abyss, leaving the farm inmates rudderless and frustrated. Biles critiques the modern ideas of progress and meliorism championed by liberal democracies. The alleged progress is a profitable enterprise for a tiny minority; for the rest, it spells a precarious existence and ever-increasing loss of freedom. In between, we also hear a cacophony of voices, each competing to offer convenient resolutions — calls for return to pure Animalism, the search for “Sugarcandy Mountain”, and blaming the present troubles on the outsiders. Each of them finds a scapegoat or a utopia, keeping the animals always occupied.

This is not a totalitarian State in a strict sense. It is a State that appropriates dissenting voices, hijacks mass movements, and betrays ideals, even as the animals — and us — emerge more hopeless than before.