“Sisters, you should encourage your husbands and brothers and sons and not worry them with your objections. If you want them to be true men, send them to the army with your blessings. Don’t be anxious about what may happen to them on the battlefield. Your piety will watch over them there. And if they fall, console yourselves with the thought that they have fallen in the discharge of their duty and that they will be yours in your next generation.” As Santanu Das points out in his magisterial India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs, “The future ‘Mahatma’ here sounds more like the finger-pointing Lord Kitchener of recruiting posters rather than a votary of the anti-war Wilfred Owen.” Das goes on to add, “Few people refashioned their masculinity as spectacularly as Gandhi, parading his vulnerable body before the world, but here [in the speech excerpted above] he harps on ‘manhood’, ‘true men’, ‘brave men’, ‘manly’ and ‘warriors’ as he invokes the Kshatriya warrior ethos.” The year was 1918 and Gandhi was on a campaign to recruit soldiers for what was then labelled the “Great” war, a war in which almost a million and a half Indian soldiers “volunteered” not, as Gandhi and the British Empire would have us believe, in the cause of izzat and duty but in order to fill their bellies and escape the vicious cycle of poverty and debt that had engulfed so many — especially in the province of Punjab, which ended up supplying almost 50 per cent of all Indian soldiers in the First World War.

In a sense, the invocation of Gandhi’s role in the war effort is unrepresentative of the many stories that are scattered throughout this richly textured book, for the overwhelming majority of the women and men whose songs, letters, drawings, photographs, memoirs, and so on, form the material backbone of India, Empire, and First World War Culture are largely forgotten today, their exploits living on — if at all — in unremembered corners of neglected archives or fading family memories. Yet, in another sense, Das’s analysis of the apparent paradox of Gandhi’s role in the First World War is wholly representative in the way in which it demonstrates just how difficult it is to create neat narratives and come to clear conclusions about any historically significant, and therefore necessarily “messy” (a word much-favoured by Das), event.

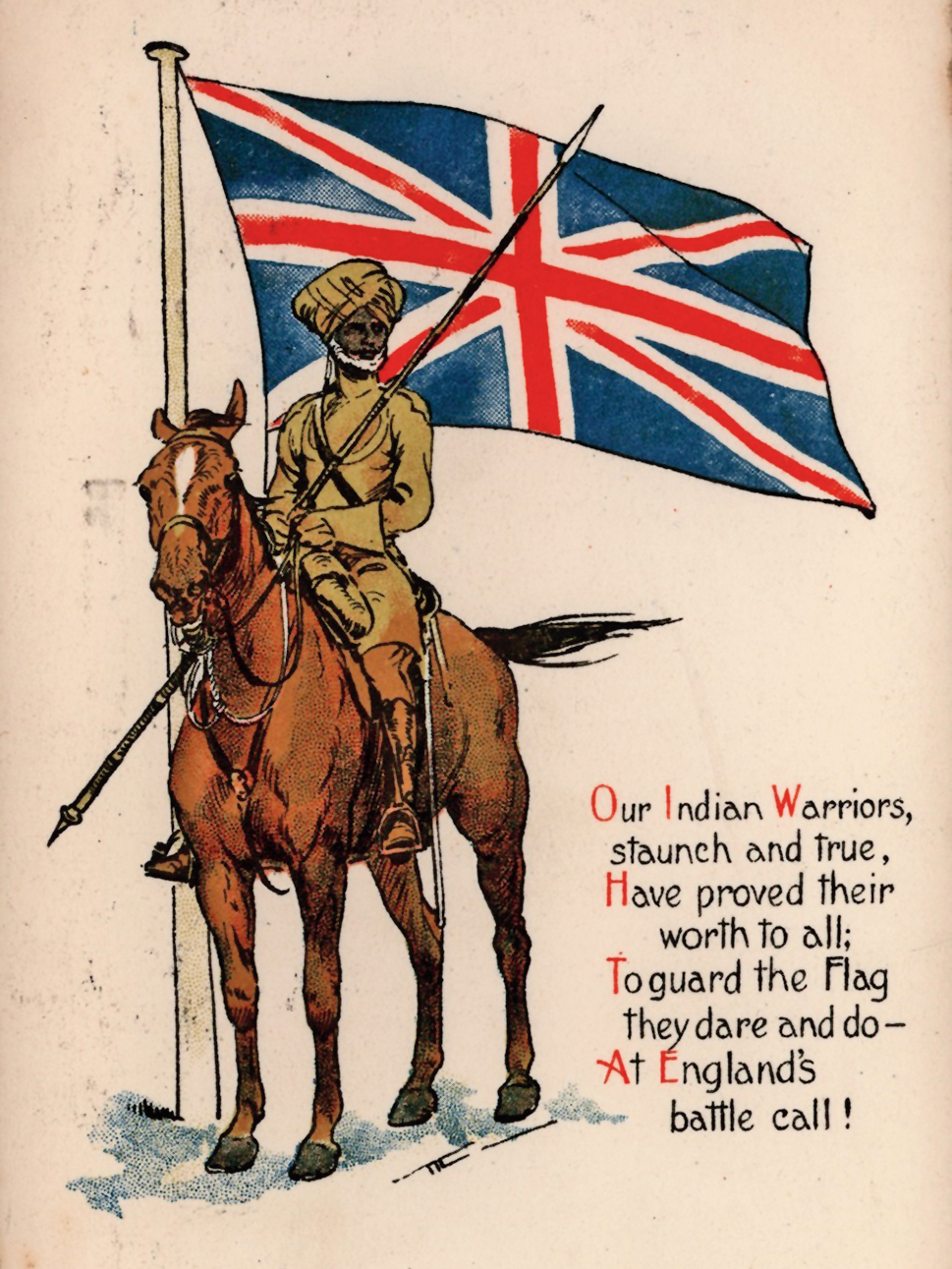

Divided into four parts — “The Restless Home Front”, “Race and Representation”, “The Sepoy Heart”, and “Literary and Intellectual Cultures” — with 10 chapters covering diverse aspects of the culture of the First World War, ranging from the representation of the Indian soldier’s body in Western visual culture to post-War attempts to construct an inclusive “human” future by the likes of Aurobindo, Iqbal, and Tagore, this is a work that is crammed full of literary, visual and aural artefacts, most of which will be unfamiliar to the common reader, and even perhaps to the specialist student of the First World War.

More than the sheer staggering variety and bewildering richness of the material assembled by Das is the acuity and nuance he brings to his examination of individual objects, which then enables him to make larger arguments about the way in which the First World War operated in and through the bodies, minds, and hearts, of those who took part in it, as well as those who observed from the sidelines. Consider, for example, his analysis of a photograph taken in September 1914 by the French photographer, Jean Segaud, of two Indian soldiers having baths by the tracks at a railway station in France. Beginning with the statement, “It is a photograph which has not made up its mind whether it belongs to ethnology, war, or art”, Das goes on to show not only how the image undercuts the convention of the boldly “martial” Sikh (for the turbaned man in the picture “looks somewhat uncomfortable — brows knitted, arms stiffened, toe curled — as the European camera… gazes at his body”; but also how the photograph neatly illustrates why “Visual theory and cultural history can be uneasy bedfellows”.

Which is to say that India, Empire, and First World War Culture is as much about method as it is about the marshalling of facts and evidence to tell a story. Das demonstrates how it is well-nigh impossible to separate the events of history (whether personal, social, or political) from the uses to which they are put — for a variety of complex, and often contradictory, reasons. The difference between the instrumental and the ethical uses of the Indian experience of the First World War is dealt with at some length in the concluding chapter, “Afterword: The Colour and Contours of War Memory”, which cautions both against the celebration of the “multicultural” nature of the War (especially in Britain) as well as the tendency to sanitize its bloody and devastating aftermath, especially for individual families (and, sometimes, whole communities). It also draws attention to the paradoxes inherent in the many buildings and structures commemorating the War, not least of which is the All India War Memorial in New Delhi, familiar today as India Gate, a monument that “has been so seamlessly assimilated into the post-independence history of the country that few even know about its First World War origins.”

India, Empire, and First World War Culture repays re-reading not just for the rich tapestry it weaves of the times and lives of the unremembered, largely unhonoured, mostly impecunious, and usually neglected ordinary Indian men who fought in the First World War, but also for the salutary lessons it draws about the pitfalls of jingoism and uncritical celebration of an event that killed, maimed, interrupted, and devastated so many millions of families across the globe. As hyper-nationalism and calls for ethnic “purity” take on increasing shrillness Santanu Das’s engaged, passionate, and rational call to look on history as “something altogether more palpable, intractable, and incorrigibly plural” can only take on greater urgency in these complicated, confusing and conflicted times.

India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs By Santanu Das, Cambridge, $27.99