What makes Nandana Sen tick? She has straddled different worlds: from being a publisher she made an extraordinary leap and became a movie star and filmmaker. She’s has written children’s books and she’s just translated her mother’s poetry from Bengali to English. In between, she’s also deeply involved in children’s rights and a charity that’s raising money to look after children who’ve become Covid orphans.

The brilliant and talented daughter of economics Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and celebrated Bengali poet and writer Nabaneeta Dev Sen, she could conceivably have coasted through life. But that’s never been her way. Even during her Calcutta school days, she was always a stand-out student and insisted on taking the road less travelled by studying advanced Bengali and Sanskrit. Both languages came in handy when she became her mother’s translator.

Covid-19 has kept Sen grounded at home in New York and she hasn’t travelled to India for the last two years – the longest she’s ever stayed away. But she filled much of the time by working on the complex task of translating her mother’s poetry and turning it into an anthology titled Acrobat. The two had hoped to collaborate on the project but her mother died of cancer soon after she had chosen the art for the volume’s cover – “Mother and Child” by Rabindranath Tagore who had been a friend of the family.

The book, containing 91 of her mother’s poems curated from six decades of writing, turned out to be an extremely challenging task, not least because of the memories that many of the works brought back of her mother who had died in November 2019. “There was an emotional challenge —I missed her excruciatingly with each poem. In her absence, every single one felt, somehow, like a message from Ma. I could almost hear her speaking to me,” she says feelingly.

Besides that, of course, was the fact that translating poetry can be far more arduous and complicated than turning the prose of one language into another. The rhyming obviously must be preserved in a totally different language. Says Nandana: “I also wanted to be faithful to her rhyming scheme, because Ma used it very deliberately to create meanings, to underscore emotions, to build surprises. She used rhyming and rhythm in a brilliant way.”

If that wasn’t enough, there was the complication of how the poem looks on the page. Says Nandana: “I also tried to keep the way the poems look on the page. Because that’s one of the ways poetry creates meaning.” For instance, when Nabaneeta wrote in iambic pentameter (a line made up of 10 syllables in a particular pattern – an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable), “I translated that iambic pentameter... There were all these ways in which I wanted to be true to the original, in form and content. But the most important thing is to reveal the soul bared in each poem, being faithful to its emotional truth.”

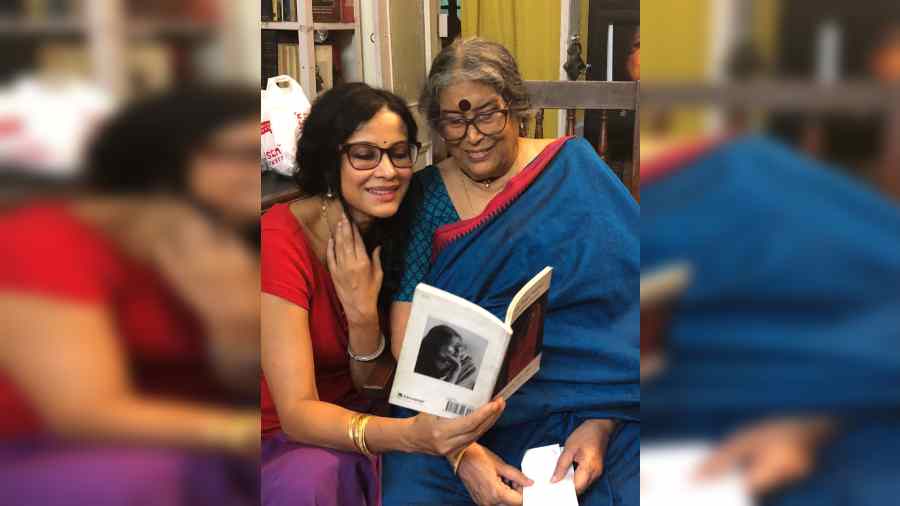

Poetry allowed Ma the freedom to write out her heart with no restraint, says Nandana. The Telegraph picture

Over 100 books to her credit

Although Nabaneeta had more than 100 books to her credit – her prose works far outnumbered her poetry collections – she always identified first and foremost as a poet. Astonishingly, despite the volume of her work, Acrobat is Nabaneeta’s first book published for an international audience. (Nabaneeta wrote in Bangla because she was deeply worried that younger generations were losing their connection to their regional heritages and languages, not just due to the dominance of Hindi popular culture but also to the proliferation of Indian writing in English).

Nabaneeta had published her first book of poetry when she was just 18 to acclaim but when she married there was a long hiatus while she focused on her family and carrying out pioneering research on the oral origins of epic poetry. But when her marriage fell apart and she returned to India with her two young daughters, she published her second book of poems (after a gap of 13 years). Nabaneeta “had left it as this kind of impossibly glamorous person, a brilliant student, she was going off to Harvard, she was engaged to someone who was destined to be a superstar. So she came back as a young mother with a marriage that had fallen apart, on the brink of a divorce, the city that had been so sad that she had left didn't quite know how to accept her because no one even in her very liberal literary circle had actually met a divorcee. So she wrote about that in a way only someone as skilled and raw as a poet could write,” says Nandana. Essentially, poetry allowed her the freedom “to write out her heart with no restraint,” she adds.

Nandana’s always made frequent trips to India but Covid-19 kept her away for two years – the longest break ever. Unfortunately, when she finally got to Calcutta in January Omicron was already raging across the country and many of her planned events had to be cancelled. Nevertheless, an online event for Acrobat organised by the Kolkata Literary Festival got an online audience of 10,000 on the first night. “That was an outcome we could not have achieved had we launched the book in person, as originally planned,” she says.

Nandana recalls one of the earlier times when she and her mother sat down to translate a few poems before a lecture at Harvard-Radcliffe. The Telegraph picture

Safe Tomorrow

She also made it to the remotest parts of the Sunderbans, for what’s called the Safe Tomorrow project in partnership with Save the Children for youngsters orphaned by Covid-19 and also Cyclone Yaas that struck when the pandemic was raging. Her efforts have been more than successful and they’ve raised Rs 50 lakh more than the targeted Rs 72 lakh. As a result, the charity has now lifted its sights and aims to support 315 children rather than the 200 originally planned. “My days were spent getting the funds and resources together, from around the world, to protect these children orphaned by Covid, while my nights were spent actually coordinating work on the ground and being in conversation with the Save the Children team in India.”

Translating her mother’s poems has, in some ways, been a lifetime’s work and not the efforts of the last one or two years. Nandana recalls one of the earlier times when she and her mother sat down to translate a few poems before a lecture at Harvard-Radcliffe. Her mother was teaching in the US at the time and Nandana a freshman studying literature at Harvard. It was well-known that Nabaneeta was a celebrated poet so, says Nandana: “We quickly translated a few of her poems so she would have the poetry to share.":

It could almost be said that, for Nandana, poetry runs in the blood. On her mother’s side, almost everyone was a distinguished poet. Both her grandfather and grandmother were poets though her grandfather died when Nandana was still quite young. Her grandmother, remarkably, began editing a magazine when she was only 10 and her mother was published both in English and Bengali when she was just seven. Says Nandana: “In our family poetry was such a strong language of communication. We would write poems to each other rather than letters; create birthday rhymes rather than birthday cards. When I left home for college, my mother would often send me lines of poetry to cheer me up or just to share with me what she was writing.” Nandana adds: “We all started writing poetry very young. It’s like a congenital condition. A genetic compulsion we have in the family!”

Nandana’s mother’s family home was the ultimate literary household with piles and piles of books; on the bed, on the floor. The Telegraph picture

Books and books everywhere

Certainly, Nandana’s mother’s family home was the ultimate literary household with books strewn everywhere. Says Nandana: “We’re totally colonised by books. It’s an old house with lots of rooms but we would get driven out of each room because eventually it would get so full of books that you would have to go to another room to find some space. She adds: “There were piles and piles of books; on the bed, on the floor. Everywhere. It was that kind of house.”

For Nandana, Calcutta has always been home and Bengali her first language. That’s despite the fact that her early childhood was spent both in the UK and the US and she later returned to university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She says: “But in between, I think I became the person that I am. Because of my time in Calcutta.” About language, she adds: “I think that has to do with being a Bengali. I think we are so jealous of our language and so proud of it.” But that didn’t stop her learning Spanish in Calcutta, “Because I so fell in love with Pablo Neruda (the poet).”

Acting, as Nandana tells it, just happened by the purest chance. Yes, she had made short films even when working as an editor at publisher Houghton Mifflin. And, after that, she studied filmmaking at the University of Southern California, she was cast by leading director Goutam Ghose in a film, “quite by accident”. She initially turned down his offer of being the leading lady and asked if she could be his assistant instead. He clinched the deal by saying she could be his assistant if she would also be his leading lady.

Movie career in vertical take-off

The film was selected for Cannes and suddenly her movie career went into vertical take-off mode. “Suddenly, I had agents in London. in New York, and quite a lot of work in India.”

Nandana insists this was a frighteningly new experience. “In our family we had always taken our intelligence, our bookishness and being articulate for granted – the fact we could discuss anything under the sun for hours. As an actor, it was eye-opening to be doing work that wasn't about arguing a case. You just had to feel it —in your gut, not in your head. You had to delve deep inside you and connect with your truest emotions.”

Her movie career inevitably moved down an unusual path. One of her movies was about a suicide bomber in New York and another about apartheid and gay rights in South Africa.

In recent years, she has turned away from film and returned to the world of words. The result has been the translation of her mother’s poetry (published by Juggernaut Books) and six children’s books. Sen and her husband John Makinson, former chairman of publishing company Penguin Random House, adopted a four-year-old girl in 2018.

So, is she firstly an actor, writer or an activist? Says Nandana: “One thing that we've learned as a family is not to be intimidated by the need to balance multiple identities, and indeed multiple worlds.”