When Oscar Wilde wrote, “[n]othing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul,” he may as well have been talking about food. ‘Soul food’ in its most authentic form is a cuisine traditionally prepared and eaten by the black American community in the southern part of the United States of America. The expression, ‘soul food’, originated in the mid-1960s, when ‘soul’ was commonly used to describe black American culture. At its core, soul food is hearty, delicious, basic cooking and recipes passed down through generations, with its roots in the US’s rural south.

But food that nourishes the soul has found expression in various forms, from oral traditions to even the oldest surviving manuscripts. From a 13th-century Scandinavian cookbook called the Libellus de arte coquinaria — it begins with a recipe for making walnut oil — to the Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine by none other than Alexandre Dumas — few know that he was a dedicated cook — the literary value of the cookbook, or a compilation of recipes, keeps gaining recognition. Dumas, for instance, brought scholarship, taste and humour to the alchemy of kitchen and table. In the Grand Dictionnaire, he makes a salad dressing right in the salad bowl — one hard-boiled egg yolk each for two people, mashed with oil and mixed with crushed tuna, chervil and macerated anchovies and tossed. “On the tossed salad I sprinkle a pinch of paprika, which is the Hungarian red pepper. And there you have the salad that so fascinated poor Ronconi.” In Elizabeth David’s Secrets de la bonne table, on the other hand, the beauty and economy of the dishes lie in the humble ingredients, the kind one would expect to find in a garden, a provincial market or a tiny farm.

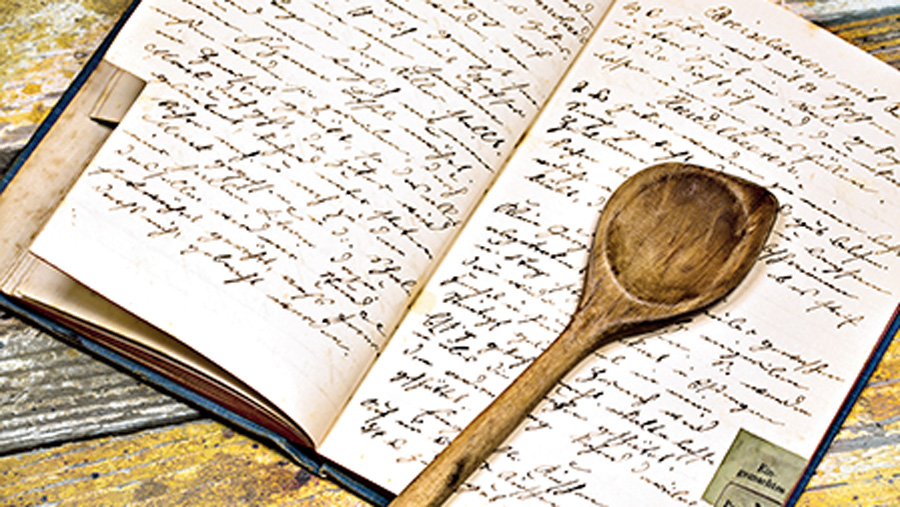

But a chief impulse behind the recording of recipes is memory. This is not just because it is important to remember how to replicate something in the kitchen that was ‘done right’, but also for the emotional and familial histories the recipes bear. The women who witnessed the Bengal famine were obsessed with reducing wastage in the kitchen; they were also concerned with creating food that nourished the soul. Their recipes were works of genius: efficient, precise, thrifty. Food was neither fetishized in their recipe books, nor a morsel allowed to go to waste. Entire dishes were made of vegetable skins, stalks and seeds — and they were delicious.

Therein, perhaps, lies the importance of the ubiquitous thakuma’r/dida’r ranna’r khata — it bears witness to the stupendous literary and historical value of the cookbook, whether they are memoirs of hunger, love, or both. Food, after all, is humankind’s most visceral way of communicating and enriching a lexicon of joy, longing, friendship, desire, rituals, olive branches, memory and love — every element inextricably linked to the human soul. June, the month that commemorates soul food, would be a good time to remember that.