Sawai Man Singh II, the maharaja of Jaipur and his third wife Maharani Gayatri Devi – or Jai and Ayesha, as their friends called them, were the ultimate Golden Couple of the Age of Maharajas. In the 1930s, Jai spent the summers in Europe, playing polo, consorting with the most dazzlingly beautiful women and leading a life of extraordinary excess. In London, he moved in the most exalted circles, stopping for tea with the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and calling on King George V. At balls he was spotted ‘draped in countless necklaces composed of outsize rubies, emeralds, sapphires and diamonds’. Excerpt:

The elitist nature of polo gave Jai a perfect entrée into the world of British high society with its slothful opulence, loose morals and fashionable depravity. The exotic bejewelled maharaja who cut a dashing figure on the polo field became a much sought after prize.

Between matches Jai (or Sawai Man Singh II, the maharaja of Jaipur) could be found dining at Veeraswamy’s – the favourite restaurant of Eastern potentates, calling on King George at Buckingham Palace, or having afternoon tea with the Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald at 10 Downing Street in the company of Kashmir’s ruler Hari Singh. In June 1935, he was spotted at the Court Ball at St James’s Palace dressed in gold brocade and ‘draped in countless necklaces composed of outsize rubies, emeralds, sapphires and diamonds. What could be seen of his turban was red and white, but it was hidden by waterfalls of diamonds,’ Tatler magazine reported. In the same week he attended a party hosted by Vijaysinhji, the Maharaja of Rajpipla, at the Savoy, which was ‘notable for the number of pretty women present’ and still going strong at 4 a.m. The following month, an elephant greeted guests at an ‘Indo-Chinese’ themed party hosted by the American-born German baroness Vivienne Woolley-Hart. Jai was photographed dancing with one of Cecil Beaton’s favourite models, the debutante socialite Bridget Poulett.

The endless rounds of parties, pink champagne and polo matches that lasted the length of the English summer offered Jai a break from the unending intrigues and stifling atmosphere of sycophancy in the attar-scented palaces of Jaipur. Leading figures of the polo-playing and horse-owning elite included Louis (Dickie) Mountbatten, who had fallen in love with the game when he visited India in 1921, and who became among Jai’s closest friends. Jai was also a frequent visitor at the home of Dickie’s older brother George Milford Haven and his wife, Nada. The smarter of the two Mountbattens – he had been a maths and engineering genius since childhood – George is also remembered for his vast collection of pornography. Lovingly bound into volumes emblazoned with the family crest, the collection specialized in images of incestuous orgies, Marquis de Sade–style sadism and bestiality. The volumes, together with an array of artificial sex organs, were thoughtfully left to the British Museum. Russian-born Nada was a lesbian whose longest relationship was with the mother of the socialite Gloria Vanderbilt. She was also close to Edwina and their extensive travels together to obscure parts of the world fuelled rumours of Lady Mountbatten’s bisexuality. Jai, the Mountbattens and the Milford Havens became part of what was known as the ‘Palace Gang’.

In the spring of 1935, the Palace Gang welcomed a new member. Virginia Cherrill was the daughter of an Illinois rancher, whose life would change forever when Charlie Chaplin noticed her on a beach in California. Having never acted before, she starred opposite the silent-era star as the blind flower girl in the 1931 classic City Lights. The film critic James Agee would later describe the final scene – in which Virginia encounters Chaplin’s Tramp at her flower stand – as ‘the greatest single piece of acting ever committed to celluloid’. Suddenly the previously unknown twenty-one-year-old was the most talked about actress in Hollywood.

After a brief marriage to a Chicago lawyer, she met the suave actor Cary Grant at a film premiere. He soon became her second husband. Grant declared Virginia to be ‘the most beautiful woman I had ever seen’ and told his friend Douglas Fairbanks that she was the ‘best lover he’d ever had’. Their marriage, however, proved short-lived. After just seven months he tried to throttle her, leaving her ‘bruised and croaking like a bullfrog’. Cary Grant then staged a fake suicide attempt. His jealousy coupled with sexual insecurity was at the root of the couple’s marital problems, Virginia told her mother.

After the very public failure of her marriage, Virginia moved to England where she was an instant hit on the party scene. When a gossip columnist drew up a list of England’s ten most eligible bachelors, the unifying link was that all but one were regularly seen in Virginia’s company. London of the mid-1930s was a world of ‘rigid etiquette, discreet affairs, and the observation of class boundaries across the limits of which only a favoured few might be permitted to leap’, observes Virginia’s biographer Miranda Seymour. For the city’s smart set, ‘life’s goal was entertainment supported by shrewdly conserved private fortunes’.

One of Virginia’s first introductions to the local social scene was a reception given by the Milford Havens and attended by Jai, Bhaiya (the Maharaja of Cooch-Behar), and Vijaysinhji of Rajpipla. At what point Virginia replaced Joan as the primary object of Jai’s affection is not clear but by the end of 1935, her photograph occupied the place of honour on his desk and he wrote her a letter begging that she come to Jaipur for Christmas. He signed off with the words, ‘Longing to be with you, Jai.’

Competing for Virginia’s affections was Bhaiya, who also wrote her heartfelt appeals to visit his state. Just nineteen years of age, rotund and bespectacled, Bhaiya was no match for the handsome and athletic Jai. He was completing his first year at Trinity College in Cambridge and had yet to be invested as the Maharaja of Cooch Behar. Jai was four years his senior, the ruler of one of India’s richest and most romantic states, a champion polo player and a consummate Casanova. ‘Jai was handsome, so amusing, so fearless: there wasn’t anything at which he didn’t excel. He treated Bhaiya like a younger brother, but that didn’t help. Bhaiya wanted to be Jai. And, of course, he wasn’t,’ said Virginia.

In the end, Virginia rebuffed both Jai’s and Bhaiya’s invitations and spent part of the winter performing in a provincial theatre play called Uneasily to Bed, which flopped so badly that it closed after one month. Stung by her refusal to visit India, Bhaiya wrote her a letter in which he stated that from the first light touch of her hand upon his he had felt that they were destined to be friends. ‘And we were friends,’ Virginia insisted. ‘Only Jai and I were all wrapped up in one another, from the very moment we met. I didn’t have much time to think about Bhaiya.’

Virginia would later recall that she fell for Jai almost as soon as they met and she knew that the feeling was mutual. ‘I think the first time Jai slept with me, he knew the truth. I adored him, no question, but he wasn’t Cary. And the divorce papers weren’t even finalized.’

The couple spent much of the summer of 1935 together. When in London they would dine at the Savoy or at Ciro’s, a branch of the famous Paris restaurant, then wander through the streets of Mayfair and Piccadilly until after dawn. Their travels took them from Le Touquet to Paris, from Biarritz to Budapest. Though she described the summer as one of the happiest of her life, their personal lives were complicated. She was still married to Grant while Jai had two wives and was about to propose to Ayesha (Gayatri Devi of Jaipur). It’s doubtful that he revealed either of these facts to Virginia. Yet this did not stop him from asking her to marry him.

Instead of following Ayesha’s lead and immediately saying yes, Virginia decided to consult Bhaiya, who seized the opportunity to enlighten her on realities of life in India and more importantly on some facts about Jai he had been withholding from her, namely, the existence of First and Second Her Highnesses. He also explained the system of purdah that awaited the wife of a maharaja. ‘I didn’t even know what the word meant until Bhaiya spelled it all out,’ she conceded. ‘I thought purdah was something you ate.

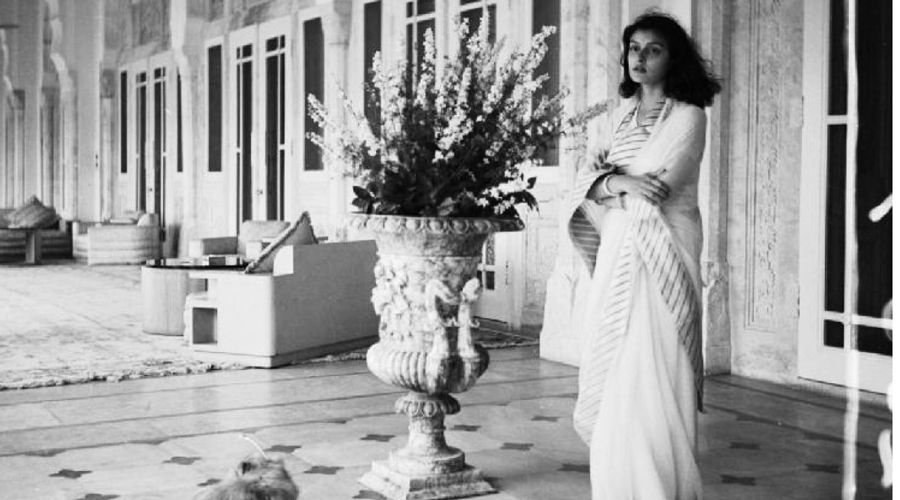

Gayatri Devi, described in Vogue as one of the most beautiful women in the world, at the Rambagh Palace. Cecil Beaton Photographs / Wikimedia Commons

Bhaiya tried to further sabotage the romance by telling his mother, Indira, that the relationship between Jai and his ‘American golddigger’ was not serious. He also warned Virginia about the pitfalls of marrying Jai. ‘You see, Jai’s life is laid out for him and he must stick to the schedule, yet it would be inhuman not to be natural, even though very occasionally,’ he wrote in an oblique reference to Jai’s propensity for having affairs. He concluded his letter by stating that Virginia should reconcile herself to becoming just another of Jai’s pleasant memories. ‘He is too nice a gentleman to forget.’ Three years later Bhaiya would caution Ayesha using almost exactly the same wording and logic. Her refusal to believe him suggests she too was ignorant of his affairs with women like Joan and Virginia, or was very good at pretending such things were the exception rather than the rule.

Bhaiya’s sniping paid off. When Jai returned to England in May 1936, Virginia’s social diary was full of engagements and her most regular escort was George Child Villiers, nicknamed ‘Grandy’. He was the Earl of Jersey and belonged to one of England’s most illustrious families. He had just publicly announced his separation from Pat, his Australian-born wife of ten years, and spent most of May and June escorting Virginia and her mother around his family estates and introducing them to his relatives. Virginia described Grandy as ‘a cold fish. The absolute opposite of Jai. You can’t imagine two men more different. By the first week of July she had resumed her affair with Jai and the two of them were once again almost inseparable.

This time Virginia decided she needed to see Jai on his home turf. A group of friends were planning a visit to India in December and she was determined to go with them ‘to case the joint’. When Grandy found out she was going to Jaipur, he added himself to the party. Grandy’s presence hardly perturbed Jai. When they arrived by steamer in Bombay, Jai’s personal bearer greeted Virginia and announced he would conduct her wherever she wanted to go and protect her. Jai lavished her with jewellery – bracelets, toe rings and anklets – until she was ‘laden down like a dancing girl’. He arranged for beautiful silk saris to be made for her and then one evening took her to Amber Fort where he regaled her with stories of hidden treasures that a ruler was allowed to touch only once in his lifetime. To Virginia, being in Jaipur was like something out of an Oriental fairytale. ‘When we arrived, there were elephants to carry us up to the front of the palace, and flaming torches and fireworks, and guards in the most beautiful uniforms, with turquoise and gold turbans standing to attention all along the facade.’ Gazing at the pink city of Jaipur from the ramparts above Amber she found it strange that all the people of the state should be ruled by just one person.

While most members of her group were satisfied with the daily round of sightseeing, shopping and eating, Virginia grew increasingly frustrated at not meeting Jai’s wives or children. Finally, after stubbornly resisting for two weeks, Jai gave in and took her to the zenana quarters at the Rambagh Palace. There to greet her was Second Her Highness. Virginia took an instant liking to Jo, whom she described as ‘a darling, so pretty and such fun!’ First Her Highness by contrast was ‘pretty tiring . . . Always stuffing herself full of medicines and grumbling about her health.’ One of Jo’s first questions to Virginia was whether she was going to come and live in the zenana after marrying Jai.

The two women developed a close relationship, so close in fact that rumours flew within the corridors of the Rambagh Palace that they were having an affair. That doesn’t seem likely as there is no evidence to substantiate the rumours, but they continued to exchange confidences through letters for years. Virginia offered Jo tips on how to satisfy her husband sexually so that he would visit her more often. A year later, Jo confided to becoming so ‘sexy’ she could ‘hardly wait for the night to come’. For her part, Virginia confessed that she wished she had never left Cary Grant.

Jo not only liked Virginia, she saw her as a passport to escape the tradition-bound confines of the zenana. If Virginia became Jai’s third wife, the three of them could travel together and have fun. Jo couldn’t understand why, if Virginia loved Jai enough to sleep with him, she wouldn’t marry him. But as Virginia later revealed, she couldn’t cope with the gossip swirling around her affair. She hated the caste system, the tradition of keeping women behind purdah and the cruelty inflicted on animals. ‘And the way everything had to be shot! Pure butchery! Tigers, elephants, leopards: It was awful, awful.’

Despite her disenchantment with the realities of life in Jaipur, she elected to stay on after Grandy and the rest of the party returned to England. Photographs contained in an album Miranda Seymour found at the back of a drawer in Virginia’s home reveal that the couple travelled together through Karachi, up the Euphrates to Basra, then across to Palestine, Athens and finally Vienna, where they parted ways. When she arrived back in England, she wrote to Jo saying that she wouldn’t marry Jai but wanted the relationship to continue in its present form. Jo wrote back voicing her approval and declared that the two people she loved most in the world were Virginia and Jai. ‘I am ready to do anything for you, even give up my life if that is necessary.’

If Grandy knew about Virginia and Jai’s sojourn, he clearly didn’t care. His first question to her when they met in March 1937 was whether she was going to marry her Indian lover. When she replied no, he handed her a diamond engagement ring. The fact that Virginia didn’t love Grandy – something that she would constantly remind him of – had little effect on their marriage plans. The impending coronation of King George VI following the abdication of his brother Edward VIII was a welcome distraction, because it meant that Jo would soon be arriving to join her husband on what was only her second overseas trip.

Excerpted with permission from Juggernaut

Book: The House of Jaipur: The Inside Story of India’s Most Glamorous Royal Family

Author: John Zubrzycki

Publisher: Juggernaut

Price: Rs 599