Book: Politics Of Hate: Religious Majoritarianism In South Asia

Edited by: Farahnaz Ispahani

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: ₹599

Farahnaz Ispahani has compiled a collection of essays that provide a comprehensive, critical and timely analysis of the rise of religious majoritarianism in South Asia. This book brings together scholars and experts in the field of politics and religious studies to examine the ways in which religious identity is used by politicians to consolidate power and manipulate public opinion in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

The essays examine historical, cultural, political and economic factors that have contributed to the growth of religious majoritarianism, charting common threads and themes. They also highlight the role of political leaders, the media, and civil society in promoting majoritarianism.

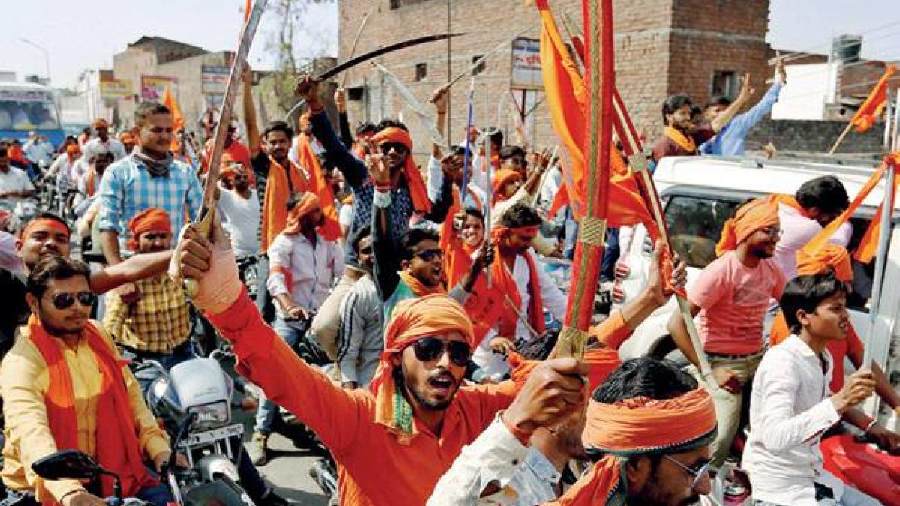

The authors identify the ways in which minority communities have been marginalised, discriminated against, and subjected to violence. They also discuss the challenges faced by these communities in organising and advocating for their rights. It is hard to ignore how Muslim communities have largely borne the brunt of this hate.

The irony of South Asian realpolitik, wherein all majoritarian governments, regardless of their demographic constitution, are in essence the same, lies exposed. Manoeuvring the politics of majoritarianism, we get a walk through the religious history of the region and the different phases of migration and displacement over the last few centuries that have impacted the languages, cultures, and shared practices in the region.

Religion and politics are conflated everywhere; the army’s role as the backbone of such governments becomes paramount in fomenting tensions and perpetrating civil rights transgressions. Hate sells for profit, while seemingly progressive and/or secular parties/politicians pander to the conservative religious elements, trapping nation states in the same vicious cycle. The (almost universal) phenomenon of majority groups suffering from a minority complex leads to skirmishes, bloodshed and despondency, resulting in a very angry populace.

The book explores the workings of hate, and the cyclical nature of majoritarian antagonism and minority radicalism, which develop in response to each other. The flow and the content of the essays, however, leave you wanting more — the text, while taking the reader through varied histories and rationales for hate politics, misses making a larger analytical point. The book would also have benefited from a more detailed analysis of the ways in which gender and sexuality intersect with majoritarianism in South Asia. While some of the essays briefly touch upon these issues, a more in-depth exploration of the ways in which such politics affects women and LGBTQ+ communities would have been a valuable addition to the book.

Despite these limitations, Politics of Hate is an important and insightful analysis of a pressing issue facing the region and should interest those who want to understand the challenges facing South Asia today.