Book: Scorching Love: Letters from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to his son, Devadas

Editor: Gopalkrishna Gandhi and Tridip Suhrud

Publisher: Oxford

Price: 1,495

One evening, shortly before Gandhi’s assassination, Devadas took Gandhi’s secretary, Pyarelal, home for dinner. This prompted Gandhi to ask his son, “Do you ever think of inviting me?” Gandhi’s quip illustrates his rejection of kinship preference, a key norm that dominates and disfigures Indian society. For decades, Gandhi had ceased to distinguish between his family members and others. Scorching and loving in equal measure, he made exceptional demands of himself and his progeny who worked on public causes with no expectation of a reward or public glory. As is well known, Gandhi’s attitude shaped the turbulent relationship with his oldest son, the mercurial Harilal. Thus, it was no mean feat for Devadas to make Gandhi’s numerous concerns his own, maintain independence of thought, and carve out a life on his own terms.

Scorching Love tells the story of Gandhi’s youngest son, Devadas, as reflected in Gandhi’s letters, some of which are being translated from Gujarati and published for the first time. Following an introduction, the volume is divided into parts that roughly correspond to a decade each. Each part is accompanied by a prefatory essay that contextualises the material.

The fourth surviving child of Mohandas and Kastur Gandhi, Devadas was born in Durban in 1900. During Devadas’s childhood in South Africa, an increasingly busy Gandhi provided an idiosyncratic and haphazard homeschooling. In later years, Devadas’s desire for higher education remained unfulfilled. In India, Devadas worked in a school founded by Gandhi in Champaran, taught Hindi in erstwhile Madras and both spinning and Hindi at Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi. In the early 1920s, he helped publish Motilal Nehru’s newspaper, The Independent, from Allahabad.

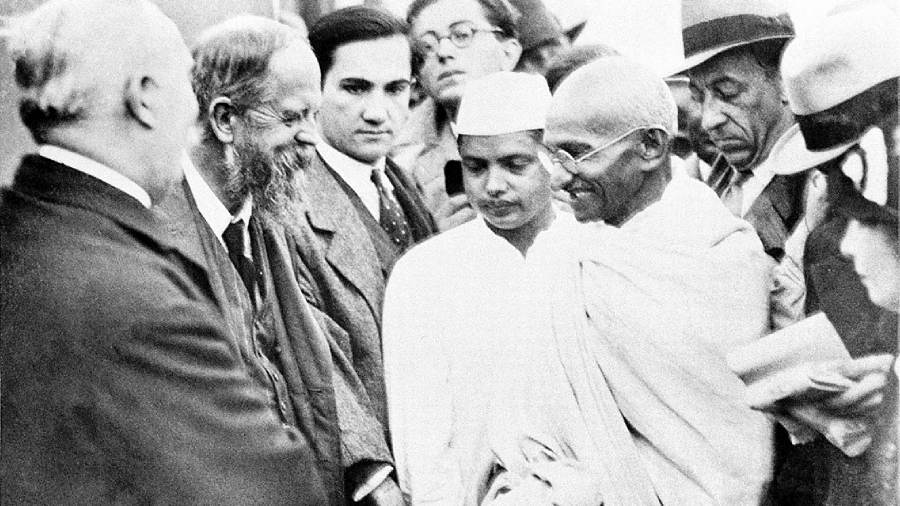

A curious blend of personal and political news, Gandhi’s missives contain advice laced with affection, love and praise as well as chastisement and scorching criticism. The letters also afford us glimpses of the many lives that are entwined with that of Gandhi. Apart from telling us about Devadas’s activities, the letters track his maturation into an independent-minded adult. Perhaps for the first time, Scorching Love assembles clear evidence of the crucial supporting role that the soft-spoken Devadas played on numerous occasions of momentous political import. If he was Gandhi’s trusted emissary to Aurobindo and Ambedkar, Devadas also provided a vital account of the happenings at Chauri Chaura and a first-hand assessment of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and the Khudai Khidmatgar. Devadas’s independent-minded analysis prodded Gandhi to revise his views on Bhagat Singh and also brought about a greater mutual understanding between Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru at a time of sharp differences in 1939.

Devadas was a loyal son, even obedient at times. But unlike some of Gandhi’s acolytes, he was not blinded by devotion. He strived against Gandhi’s views on modern medicine and was critical of Gandhi’s infatuation with Saraladevi Chaudhurani in the 1920s and bhramacharya practices in later years. Devadas was also a righteous Benjamin in accusing Gandhi of the neglect of Kasturba’s welfare. Decades in the limelight had inured Gandhi to public and private criticism, but this charge stung him. Gandhi demanded that Devadas withdraw his allegation and went on to mount a vigorous defence of himself against a range of charges from the son. Evidently Devadas could also be sharp, if not scorching.

In 1933, Devadas married Lakshmi, the daughter of C. Rajagopalachari. The marriage transformed the tenor of Devadas’s life: he took up a position at The Hindustan Times in Delhi and went on to edit the paper. As Gandhi remarked, “Marriage and Delhi have done him good.” But all along, Devadas was plagued by poor health and Gandhi chastised him for a lack of discipline in diet and exercise. In this regard, the son was not a chip of the old block.

The value of the letters presented is enhanced by the intimate knowledge of the first editor who is the youngest son of Devadas and Lakshmi and a Gandhi scholar of first water. His filigreed understanding of Gandhi’s life and the Gujarati language is matched by that of his co-editor and is visible in the deft and illuminating Introduction and the prefatory essays. However, one wishes that in lieu of some of the discursive details of Gandhi’s activities we were told more about Devadas’s life. The volume sorely lacks a substantial description of Devadas the editor, and his life between 1948 and an untimely death in 1957. One also wishes that some of the minor blemishes in editing were avoided and that the publishers had chosen a larger font that would have made for comfortable reading.

The novelty of the material and the scholarship of the editors combine to make Scorching Love a valuable addition to the vast corpus of literature on Gandhi. It addresses a long-standing gap in our understanding of the life of Gandhi’s “youngest son and valued comrade”.