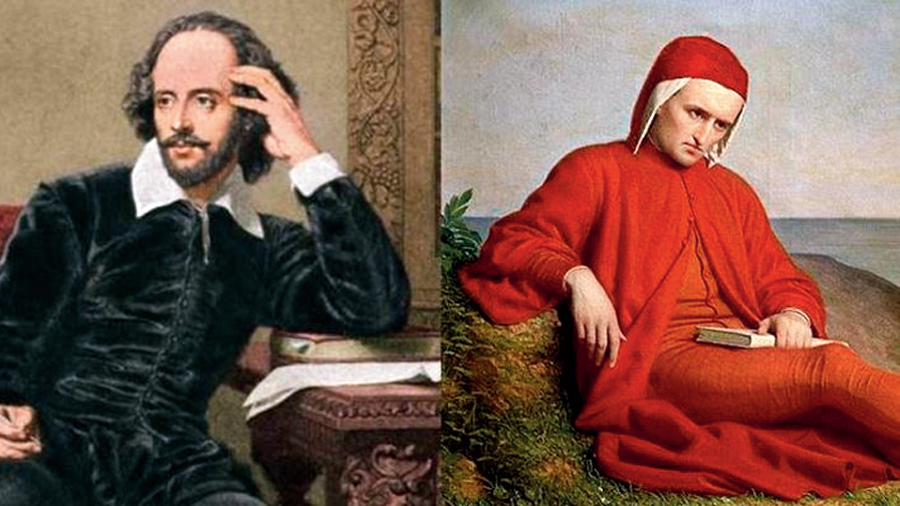

Dante Alighieri is believed to have said that the hottest place in hell is reserved for those who refuse to take sides. But he seems to have got it all wrong. All hell broke loose recently when the German journalist, Arno Widmann, picked a side. In a piece for Frankfurter Rundschau, he argued Dante was entirely beholden to French medieval troubadours, the poet-musicians who wrote verses on love. Widmann further fanned the flames of controversy by comparing Dante to William Shakespeare, claiming that the latter “in his amorality was light-years more modern than Dante”. This started a literary gale, with newspaper articles, radio shows, letters to the editor and irate tweets pouring in. Most found fault with Widmann, but some were also on his side.

While there are plenty of obvious differences between Dante and Shakespeare, ‘morality’ is not one of them. In fact, the two poets separated by nearly 250 years shared an idea of morality that surpassed religious and social connotations of the word. Shakespeare did not explain his morality as formally as Dante did — the latter explicitly stated his didactic motives in a letter to Cangrande, Lord of Verona and protector of the exiled Dante. Moreover, the Bard’s works are set firmly in this world and, unlike Dante, who pictured Hell and Earthly Paradise in paint, Shakespeare did not conjure a mystic vision, preferring an allegory to impart a moral lesson — is that not one of the purposes of tragedy?

Take, for instance, Measure for Measure and Canto XVI of Purgatorio. Rumour has it that Shakespeare read Dante’s Inferno just before he penned the play. These may not be the greatest work either poet has ever produced, but in their intellectual focus both texts have one inescapable motive: to grasp the true nature of government. In Measure for Measure, the Duke who leaves a strict deputy in charge of easy-going old Vienna, creates a quandary between morality and the letter of the law when it comes to governance. Young Claudio, who gives Juliet a child before their marriage, becomes an example of “the nature of... people” prior to any moral or religious guidance. In the end, the Duke shows how morality trumps reason when it comes to governance. This is because morality has within it a scope for redemption under the right guidance as opposed to reason, which demands retribution.

The angry soul in Canto XVI has its rational faculties intact, but is blinded spiritually by the acrid smog around it. The smog stands for moral turpitude and the soul is guided through it by Marco who says that this blindness and corruption are responsible for the chaos that Italy had descended into during Dante’s time. Interestingly, morality in Dante’s eyes is freed from the clutches of religion as he lays equal blame on Church and State when it comes to seeking totalitarian control. Dante thus argues for the rejection of both reason and religious law when it comes to governance, asking man to instead act “in accordance with moral and intellectual virtues”.

Where the two poets differ is that while Dante presses his readers to think (and to enjoy thinking), Shakespeare provides more definitive answers to the moral problems and questions he raises. Dante’s idiom may be foreign, his world view long vanished, but much of what he says about morality, politics, language and love has a bearing on our lives today, and in this he and the Bard are kindred spirits.