Book: Pure Evil: The bad men of Bollywood

Author : Balaji Vittal

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 399

In a conversation with the author, Raymond Chandler, in 1958, Ian Fleming, the famed creator of the British secret service agent, James Bond, remarked that he found it “extremely difficult to write about villains… a really good solid villain is a very difficult person to build up, I think”.

Yet, Fleming created some of the most memorable villains — Bond’s recurring nemesis, Blofeld, Auric Goldfinger, Hugo Drax, Le Chiffre, Rosa Klebb...

Like Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty or Satyajit Ray’s Maganlal Meghraj, the best villains are as brainy as — if not smarter than — their hunters.

Hindi cinema, too, has been fascinated with villains — from the dacoits of the Chambal ravines and foreigners chewing on cigars and speaking in heavily-accented Hindi to landlords, smugglers, gangsters, terrorists, white-collar criminals, scheming relatives and evil women. Even a film like 83, on the triumph in the cricket World Cup under Kapil Dev, couldn’t resist the temptation of portraying the mighty West Indian pace bowlers as snarling, baying-for-blood players.

This story of villainy in Hindi films is what the author, Balaji Vittal, seeks to explore in his book, Pure Evil: The Bad Men of Bollywood. Vittal, the co-author of three books, including a national award-winning biography of the composer, R.D. Burman, has, in his first solo effort as a writer, detailed the various kinds of Hindi film baddies over the decades.

In the process, Vittal has penned much more than a book on villainy. Pure Evil is also a reflection of the socio-economic transformation that India went through from the decades preceding Independence and over the 70 and odd years since.

The author has divided his book into seven sections, each delving into the type of villains that dominated Hindi films through this sweep of time. The colonizers and foreign villains are, for instance, clubbed under “Mera Bharat Mahaan”; gangsters, smugglers and terrorists are written about in “Don ko pakadna mushkil hai”; dacoits and ruthless moneylenders and land-usurpers are bunched together in “Baaghi”.

There is also a section on the “anti-hero” called “Tum log mujhe dhoond rahe ho”, which starts with the character of a conman with a good motive played by Ashok Kumar in the 1943 blockbuster, Kismet, a film that became the template for future potboilers.

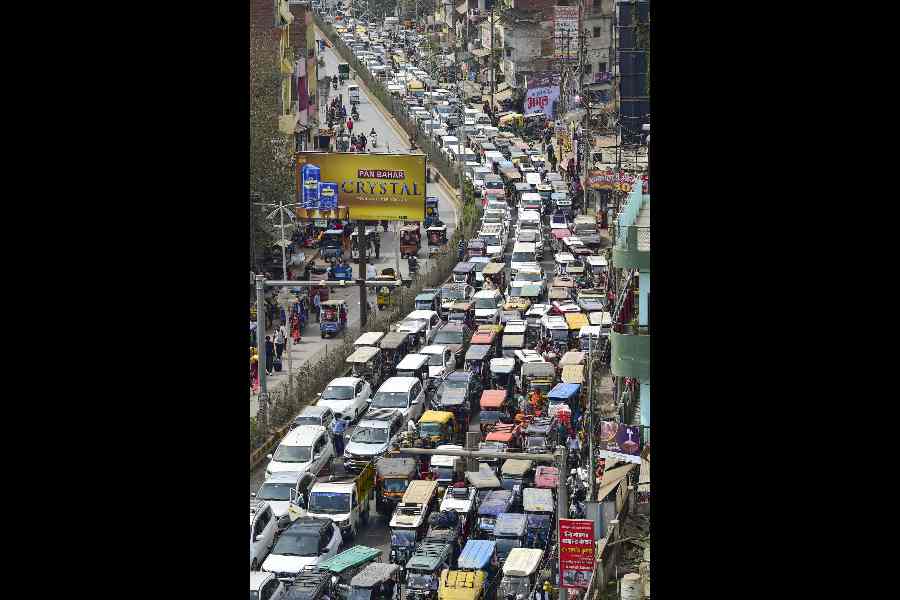

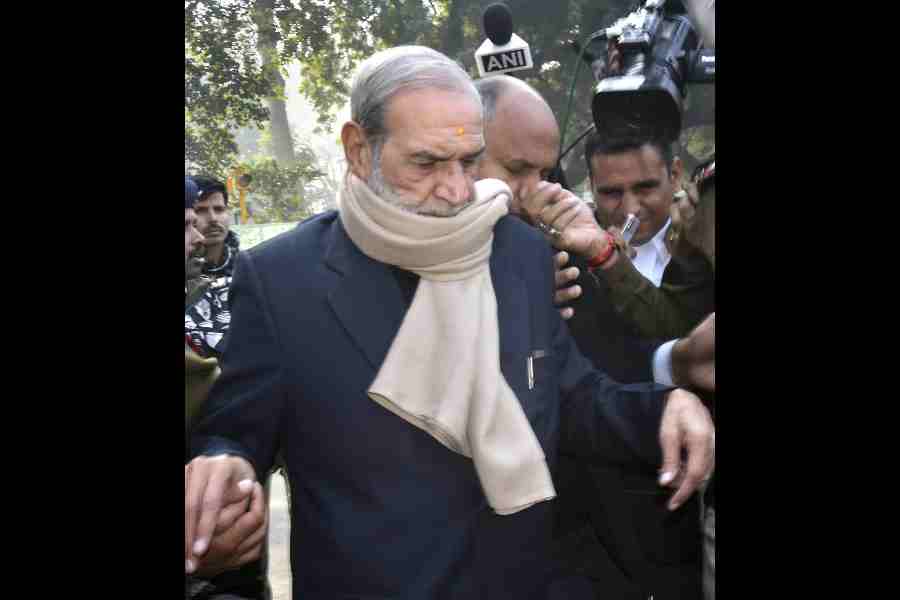

Politicians, too, started becoming the face of evil as society increasingly got disillusioned after the initial heady years of hope and aspiration following 1947. The author tracks this through various chapters, listing the films that deal with the nexus that forms between people’s representatives and unscrupulous government officials, builders, businessmen and so on.

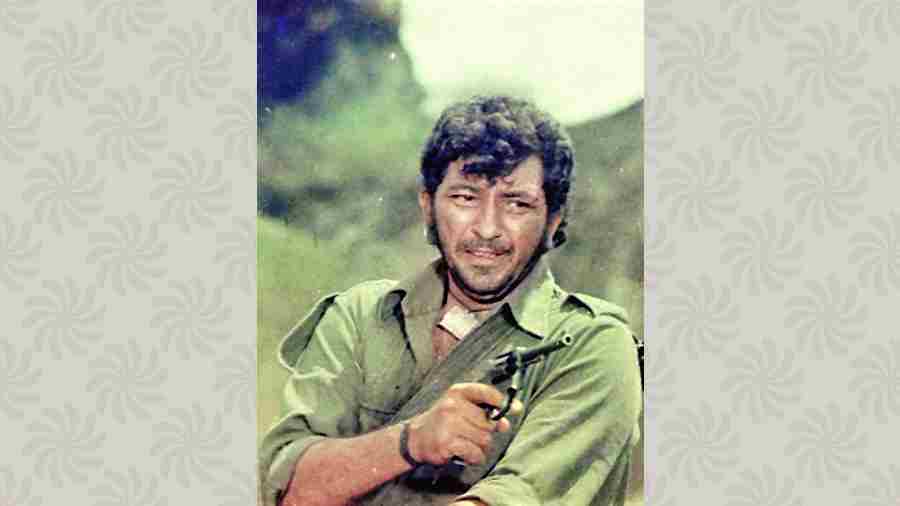

Through his work, Vittal also pays tribute to the actors — the likes of Pran, Prem Chopra, Danny, Ranjeet, Ajit, Madan Puri and K.N. Singh — who played these villains, but often got overshadowed by the hero, the good guy.

Of course, there were exceptions: Amjad Khan’s Gabbar Singh (Sholay, 1975), Amrish Puri’s Mogambo (Mr India, 1987), Kiran Kumar’s Lotiya Pathan in the 1988 hit, Tezaab (although Vittal believes the character got “discounted” in the “Ek Do Teen countdown”), Kulbhushan Kharbanda’s Blofeld-inspired Shakaal (Shaan, 1980) and Nana Patekar’s Anna Seth in Parinda (1989) went on to achieve cult status in the world of film villainy.

If one expected a book like this to be fast-paced, like some of the films it mentions, it is not. There are several layers to every chapter which one has to navigate in order to grasp the big picture that the author seeks to portray.

The lay reader, though, may find mining through the deluge of information a tad bit tedious. The author, while discussing a villainous genre, flits from one film to another to a third and a fourth, a style that sometimes gets a bit overwhelming. What one misses is — as Fleming said — the fleshing-out of a character with stories woven around it. Such a tactic would possibly have made Pure Evil an easier read.

The book could also have done with better fact-checking. In his chapter on foreign villains, for example, the author writes that the film, Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey, was adapted into Manini Chatterjee’s book, Do & Die: The Chittagong Uprising 1930-34, when, in fact, it was the other way around. Chatterjee’s work was published in 1999, a good 11 years before the film’s release. Similarly, the 2001 Amitabh Bachchan-Manoj Bajpayee starrer, Aks, was not so much inspired by Face/Off (1997) as it was by Fallen (1998).

Another quibble is the lack of an index. For a work of this nature, an index would have helped with cross-referencing. For connoisseurs of Hindi film history, though, Pure Evil is a treasure trove of information, anecdotes, and nuggets of trivia spanning about 90 years of movies. How, for instance, was the 1949 film, Apna Desh, a possible first in Hindi cinema? How did a production executive in producer-director Nasir Husain’s unit come to be “immortalised” in the annals of villainy? Which film in which Smita Patil plays a character with negative shades was partly inspired by Clint Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me (1971)?

Ian Fleming found it difficult to write about villains. Vittal has attempted to write the history of villainy in Hindi films, an equally arduous task, which, in spite of its shortcomings, has portrayed the changing mores of India’s society through the passage of time