The power of immense powerlessness

The Thirty Third - Thirty Fourth Cup

January 7, 2011

The tea simmered and slowly turned red while John watched on, carefully. He stood in the kitchen contemplating the purpose of our gathering, but didn’t say much at all. He was holding back his words until the tea was ready. John wanted to begin this memorial properly. He wore a heavy turquoise necklace to acknowledge the occasion, which reminded me of jewellery from Afghanistan. Soon we joined Carli in the living room with three cups of hot nun chai.

Carli mentioned that John was born in India, and, as if reading direct from the pages of a novel, he started to describe his early life. “It all started in Shimla, in my mother’s womb.” He spoke of those first few months and his birth in a “modern” hospital in Calcutta as though he actually remembered it. “See this birthmark,” John pointed to something that resembled a ragged, overgrown, empty piercing on his left earlobe. “My mother commissioned a portrait of a Tibetan couple just before I was born. But for some reason the artist forgot to paint their jewellery — and instead they say the jewellery found a way to manifest itself in my ear.”

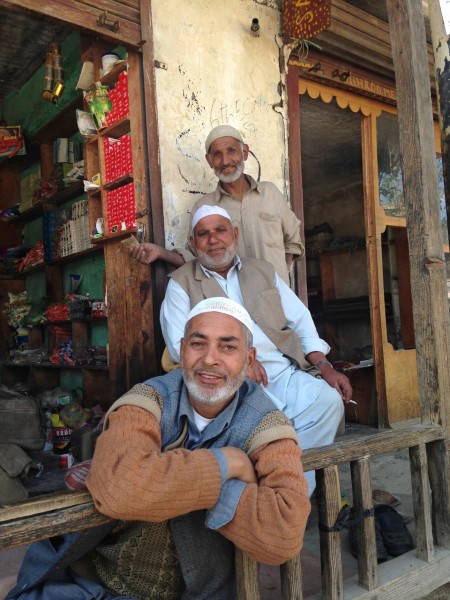

John spoke nostalgically about his childhood in British India before Partition. John’s Russian mother had a special costume made for him by a local Muslim tailor, which he would wear when dancing for his father’s guests. During Partition this tailor decided to go to Pakistan and suddenly left their locality. One day John heard his father telling someone else their family’s tailor had died — his throat had been slit. John remembers being made to dance in the costume the tailor made, “I remember dancing, the rage and anger I felt almost exploding with every move.” I asked John if he remembered who he was angry at. “It was simply the injustice of it. Hindu or Muslim, I didn’t know or care who killed him. I just knew he was gone. Injustice is a powerful thing. Whether it’s a child at school who has been wrongly accused of stealing a pen or someone’s premature death — like those in Kashmir — injustice usually lies at the heart of anger.”

Injustice and anger brought our conversation to stone-throwing in Kashmir. Carli raised her arm back as if throwing a stone in the middle of the living room. She imagined the feeling of release it could bring. It seemed like a moment of power in the face of immense powerlessness. “How did you first end up in Kashmir?” asked Carli.

Sankarshan Thakur

“Yes,” John continued, “What was it about the place that captured you? Why are you still talking about it?” In one way, Kashmir embodies a childhood fantasy that still pulsates with life. The mountains, the rivers, the wooden homes — it’s a landscape filled with the warmth of people, and chickens running at your front door. Green trees in summer and snow in winter. Fresh, cold drinkable water flowing from a mountain source. Cosy clothes and delicious food. But it is a fairy tale that has been tragically betrayed, burnt and bloodied. That is something difficult to walk away from. Perhaps John was right — maybe it was the injustice of it all that held me there. Perhaps that is what keeps many people there, struggling with hope and anger.

“Unnatural” and “absurd” were words John used to describe the partition of South Asia. “What would Gandhi say about Kashmir today?” Carli ruminated, “What does he mean in Kashmir?” We spoke about the complexities, contradictions and compromises that gave shape to Gandhi’s life. There is much more to Gandhi than the popular image of non-violent civil disobedience that dominates in the West. He was, first and foremost, a political strategist. And one with questionable beliefs on caste, gender and celibacy. His refusal of modernity was politically motivated. But it was Gandhi’s revelatory remark that Kashmir would prove to be the true test of India’s secularism which seemed most pertinent today.

Sankarshan Thakur

Via India and Sarajevo

The Eighty Second Cup

May 1, 2012

Varsha is an artist who grew up in Gujarat and has lived in Bangkok since 1995. As co-organiser of the Thailand-based Womanifesto, feminism and the role of women in the arts have been important components in her work over the years. When we met, in what Varsha described as an old local’s café in Bangkok, she placed a book on the table between us — Speaking Peace: Women’s Voices from Kashmir. It contained black and white photographs of Kashmiri women, their families and their stories. There was one portrait of a woman whose eyes reflected back the story of violence that had engulfed her home, the shape of her mouth torn by war. Varsha began our conversation by reminding me that women always bear the brunt of war.

I had prepared the nun chai earlier on a gas burner at a small food-cart on the corner of one of Bangkok’s busy city lanes. When I poured the nun chai for Varsha, more than an hour after it had come off the gas, it was still steaming hot. As she tasted the nun chai, Varsha spoke immediately of her memories of Kashmir. “I visited Kashmir once in the 1970s, when I was a school girl. At that age I knew nothing about the real political situation, but now I can see that since the time of Partition there has always been trouble. I remember the snow, our cold rosy cheeks and a sheep we saw slaughtered by the side of a road.”

Hindu or Muslim, I didn’t know or care who killed him. I just knew he was gone. Injustice is a powerful thing... usually lies at the heart of anger

“I also knew a Kashmiri trader who would visit our home in Gujarat every winter selling Kashmiri shawls and embroidered saris.” Varsha said he was probably the only Kashmiri trader in Gujarat at that time, and he always travelled with his son who, as Varsha recalls, was about eight or nine years old. “Last year, in 2011, I went home to Gujarat during the winter. Imagine, after decades, I came across that same boy, who was now a man continuing his father’s trade. He called me ‘baby’, just like his father did all those years ago.” Varsha asked how life was back home, “He simply shook his head and said, ‘That is no way to live a life.’”

What Varsha knew of Kashmir reminded her of Sarajevo. She had gone there some years ago for an artist residency. One day Varsha’s friend said she wanted to take her for a walk. “She didn’t tell me where we were going, but eventually we arrived at a sidewalk. It was a normal looking sidewalk, to my eyes at least, until she told me this is the place where her father fell to the bullet of a sniper. This was the first time she had returned here since his death.” Varsha assumed that Kashmir must also be filled with such memories.

Varsha was friends with a group of female Iranian writers. She described their courage and the depth of the political and social obstacles they face from religious police who intervene in daily life and the government’s strict censorship. Then, quite suddenly a song that played loudly on the café’s crackling speaker system broke our conversation. I tried to keep speaking through the noise, only to realise everyone in the café was standing. Varsha gently explained, “This is the national anthem, we have to stand.” She smiled, “We have our own kind of religious police here too. We’ll talk about it later.” Varsha and I stood there silently looking at each other’s faces for the duration of Thailand’s national anthem. I soon learnt it was played every day at 6am and 6pm across the entire country and for the duration of the anthem everyone had to stand.

Excerpted from Cups of nun chai by Alana Hunt; published by Yaarbal Books