In the Acknowledgements section of the novel, I Have Become the Tide, Githa Hariharan explains why she, presumably a “privileged person in terms of caste or class”, felt the need to write about “the terrible inequalities” that “ravage the lives” of so many of “our fellow citizens”. To engage with life in India today, a writer needs to take a stand on these inequalities even if she cannot ‘know’ the “lived experience” of those “historically oppressed”. The novel, therefore, is consciously political in the broadest sense. This sense animates, although more intimately, the research of P.S. Krishna, the professor in Hariharan’s story who writes a book investigating the lineage of the saint-singer known as Kannadeva — his grandfather’s caste work was skinning cows — and the authorship of the songs ascribed to him. You are not Dalit, a young woman tells Krishna at the end of one of his lectures, you cannot understand a cow-skinner’s life. Is that not another form of appropriation?

Hariharan’s insistence on this issue addresses two linked aspects of history. One comprises the sharp edges of various identities that can today question the ‘right’ of ‘others’ to stray into their territory. The other comprises an awareness of the rich literature in Indian languages from the oldest times that tells of the inhuman cruelties and apparently inescapable physical horrors heaped on the ‘oppressed’. But ultimately it is the English language that ‘delivers it to the world’ — a phrase used by Krishna’s young questioner. The recent flood of English translations of Dalit writing and Dalit writing in English complicate Hariharan’s context further.

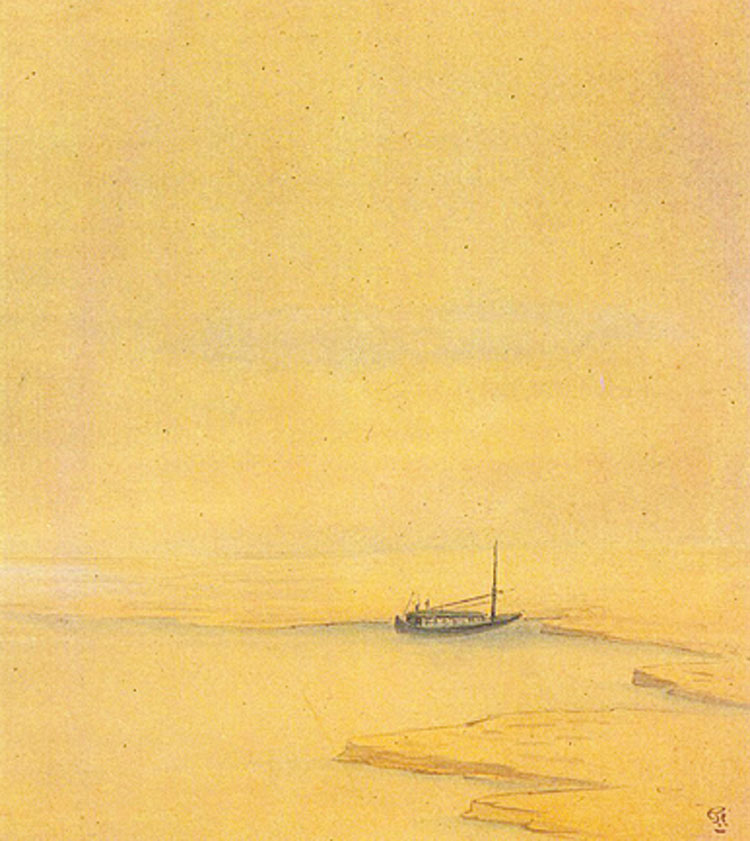

Krishna’s research forms one of the three narrative threads in the novel. Another recounts Kannadeva’s development, beginning with his father, who becomes a washerman working and singing by a restless river — the “river of a thousand faces” — after escaping from an inherited life of cattle-skinning. His new life is made possible by Anandagrama, a community modelled on the idea of an equal, casteless society on the margins of the big city. A tale of three school friends, Asha, Ravi and Satya, makes up the third strand. Separated by the demands of higher study, each tries to protect the other two from the daily humiliations they face in their colleges as members of the scheduled castes. It is Krishna’s book on Kannadeva that ties the stories together, as do the songs through the ages that resonate with a love of the earth as well as an irredeemable despair. Hariharan is quite marvellous in her rendering of Kannadeva’s songs and contemporary Dalit poetry, and her quick, vivid prose suggests the flow of water that is central to the theme.

But the easy flow also makes the novel a bit too pat. Krishna is too close to M.M. Kalburgi, as Kannadeva is probably to Basava. Is it Rohith Vemula who is invoked in Satya’s fate or Chuni Kotal? It is as though, in spite of the author’s best intentions, harsh, unmusical complications slip out of our grasp. Perhaps Srikumar and Muthuraja, killers in two ages, are the best developed as characters, apart from Krishna. Since the dynamics of oppression remain unchanging in the novel, it is difficult to respond to the hope at the end except wishfully.

I Have Become The Tide; By Githa Hariharan, Simon & Schuster, Rs 499