The 19th century story of the romance and consummation of Bidya and Sundar by Bharat Chandra Roy; translations of 15th century Sanskrit texts such as Jayadeva’s Ratimanjari, which has 125 verses on the art of lovemaking; Bhanudatta’s Rasamanjari, a long poem on the passion of Radha and Krishna; Naba Bibi Bilas (1825) and Naba Babu Bilas (1831), satirical books by journalist and poet Bhabanicharan Bandyopadhyay about the life and work of prostitutes and their patrons. These were some of the stories that flowered and made for brisk business at Battala in the early 19th century. Then there was Uff Mahanter E Ki Kaaj, which was about an adulterous affair between a priest and a housewife. Badmaesh Jabda written by Prankrishna Dutta welcomed the Contagious Diseases Act of 1868, introduced to prevent the spread of venereal diseases, as a gift of the British government to punish both prostitutes and their patrons. And Amar Guptakatha was written by some babu under an alias and is essentially an autobiographical narrative of illicit relationships and incest among Calcutta’s gentry.

From Butto Krishto Paul Avenue in north Calcutta’s Sovabazar area to the erstwhile Lower Chitpore Road crossing is a 10-minute walk. A stone’s throw from here is Battala, so named after a grand banyan that has been gone over a hundred years now. There is no signboard and neither will anyone point out the exact spot of the Bandha Battala or paved banyan tree. The area is now filled with decrepit letterpress printers, utensil shops and booking offices of jatra shows. But once upon a time, this used to be a publishers’ hub.

In fact, 2020, which will henceforth be remembered as the year of the coronavirus, was the bicentenary year of Battala literature.

In the early 1820s, Biswanath Deb opened a printing press not very far from Battala. People would gather at Battala, enjoy musical soirees and gossip. Apart from being the centre of town, what contributed to the spot’s popularity was its proximity to the red-light areas of Sonagachhi, Rupagacchi and Harkata Goli. Deb, who started his printing career with a book on elementary mathematics, soon branched out into erotic literature. Moneyed babus constituted the main buyers of erotic books, which included not just literature on the art of lovemaking, but also compilations of songs sung by prostitutes, scandals in contemporary society, farces and so on.

Bidyasundar had opened the floodgates of erotic literature. Archivist and musician Devajit Bandyopadhyay says, “Bharat Chandra Roy liberated poetry and musical compositions from religious trappings. Bidya and Sundar were mortals unlike the godly Radha and Krishna, so the poet had the liberty to narrate their romantic and sexual escapades in a manner that was till then unexplored in Bengali literature.” Bharat Chandra described his heroine’s beauty in minute detail, as also her hungering for Sundar. His description of the pair’s physical intimacy is lyrical, impassioned and leaves little to the imagination.

The Bengali bhadralok, no matter what his private engagements, denounced the Battala books in bhadra samaj as ‘low literature’ produced by ‘hack writers’ and peddled by ‘low-end publishers’

The first printed version of Bidyasundar came off a press owned by a British printer in Bowbazar but its success inspired many fledgling printer-entrepreneurs of Battala to print their own versions. Biswanatha Deb published an edition of Bidyasundar in 1920.

There were hawkers who sourced the choti or chap books by the hundreds in wicker baskets and sold them across the city and the hinterland. The Battala publishers also printed religious texts — Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas — biographies, almanacs and textbooks. But the irony is that for future generations, the label Battala literature came to be synonymous with cheap erotica.

The infamy stuck when educator and Anglo-Irish priest Reverend James Long raised objection to the printing of these “obscene books”, some of which he said were a “beastly equal to the worst of the French school”. As for the bhadralok, no matter what his private engagements, denounced them in bhadra samaj as “low literature” produced by “hack writers” and peddled by “low-end publishers”.

Long’s campaign forced the British administrators to pass the Obscene, Books and Pictures Act of 1856. Prominent members of Bengali society, including social reformer Keshab Chandra Sen and writer and administrator Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, formed a society to denounce obscenity and called for a ban on these books. Many Battala publishers were arrested and punished; editions were confiscated; many libraries stopped keeping these books and many people associated with these publications went underground.

The puritans might have hacked at the grand banyan, but fell it they could not. A large section of Calcutta’s gentry, led by the founder of Sovabazar Rajbari, Raja Nabakrishna Deb, came forward to protect the urban folk culture of Calcutta. “Apart from erotica based on Kama Sutra, there were books that reflected changes afoot in contemporary society,” says Bandyopadhyay, who had gone looking for the remains of the industry on Lower Chitpore Road in the late 1980s.

By then, most of the publishers had shut shop. Bandyopadhyay managed to find some editions across city libraries as well as the archives of the British Library in London. He talks about books such as Amar Guptakatha, Mahanta Elokeshi Sangbad and Badmaesh Jabda. Beyond the risque element, so many years later, they lend an insight into the different sides of Calcutta of the 19th century.

In his own book Bai Barangana Gatha, Bandyopadhyay discusses two autobiographies that came out of Battala — Sikshito Patitar Atmacharit or The Memoir of an Educated Prostitute by Manada Devi and Amar Kotha or My Story by Binodini Dasi, who was born to prostitution, started her career as a courtesan and later became a theatre actress.

In his book The Parlour and the Streets, cultural historian Sumanta Banerjee writes, “Battala publications offered a counter-culture vis-a-vis the ‘high’ literature of the educated bhadraloks, who mainly followed the hegemonistic model of a ‘standardised’ Bengali written style.”

One of the few Battala publishers to survive Long and the bhadraloks’ “civilising mission” is Diamond Library. As the publishing industry ebbed away, jatra companies set up shop in Battala.

Says Baidyanath Seal, a co-owner, “We no longer have a printing press. Now our lifeline is religious literature, books on Vaishnava kirtan. We also sell books on astrology, tantra, homeopathy and sex education.”

The Sils — not to be confused with the Seals of Diamond Library — were among the oldest Battala printers, but shifted base to College Street, the seat of “standardised” Bengali literature, some years ago. Mohan Sil, who co-owns Akshay Library on College Street, says, “My grandfather Purna Chandra founded the press over 150 years ago. We are the fifth generation.” Akshay Library makes a brisk business of the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Gita and Purohit Darpan, a manual for Hindu priests. Their bestseller, however, is Benimadhab Sil’s panjika, an exhaustive almanac.

Writer Nalini Bera, who grew up in a remote village in West Midnapore, rues the decline of Battala literary culture. He talks about his childhood in the late 1950s when he saw the elderly buy low-priced Battala books — mostly religious texts — at weekly haats or fairs. According to him, these cheaply produced books made the printed word accessible to many first-generation learners. He also mentions the nishiddho or forbidden books. “A newly married cousin secretly bought an illustrated version of Vatsayana’s Kama Sutra from the haat. We teenagers devoured it voraciously when the book wrapped in sacred red cloth was passed around surreptitiously.”

Bera believes Battala books had influenced “high” literature too. Novels such as Hemlata Ratikanta (1847) and Kaminikumar (1856) are said to have influenced Bankim’s Devi Chaudhurani. That the writer had once termed them “adi rasalo itar bhabalu pustika” — salacious books for the filthy and low-minded — is another matter. Bandyopadhyay too talks about the hypocrisy of some “elite” writers who wrote such books from the comfort of aliases.

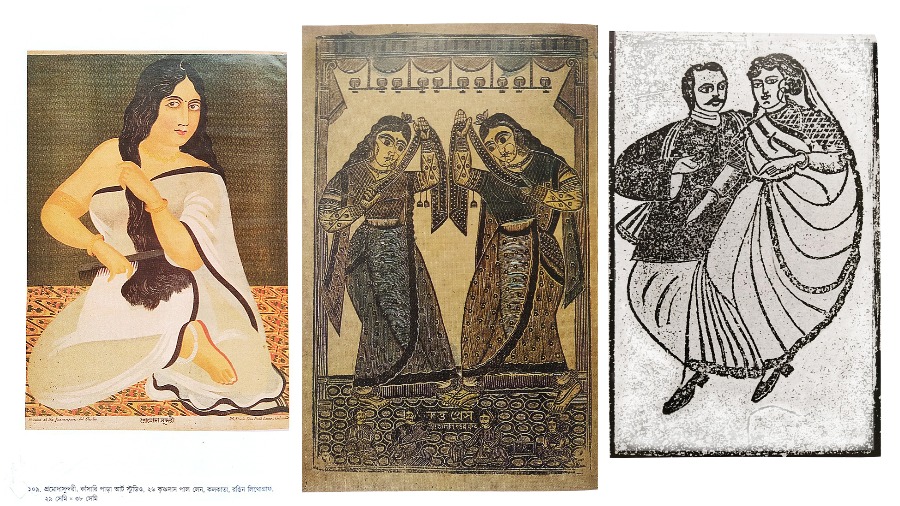

The Battala books were also documents of popular art forms such as woodcut and lithographs that were used as illustrations. Painter-researcher Ashit Paul had interviewed some of these artists in the late 1980s. According to him, most of them were self-trained and were primarily goldsmiths. “Early artistes were deeply influenced by patachitra painters of Kalighat. But there were artists like Priyagopal Das who developed a unique style of engraving, a combination of Indian miniatures and British printmaking.” In his upcoming book Kolkatar Kathkhodai, Paul analyses art works of some of the woodcut artists, such as Hiralal Karmakar, Krishnachandra Karmakar and Nrityalal Datta.

Early researchers of the Battala literary genre, Sukumar Sen, Binoy Ghosh and Nikhil Sarkar (known as Sripantha), had identified how the books had offered a united platform for publishers, writers, artists and booksellers of both Hindu and Muslim origins. The tales of Laila Majnu, Hatim Tai and 1001 Arabian Nights were illustrated with erotic woodcuts by Hindu artists. This inclusiveness gave credence to the mixed dialects of the masses that included words from Urdu, Farsi, Arabic and patois in the print media. Experts called his linguistic style dobhashi literature.

According to Sen, the sudden end of Battala publication happened at the time of the communal riots of 1946-47. Many presses were destroyed and books burnt. Some involved with the trade began shifting to College Street; most others just forsook the occupation.

Ironically, since the 1960s, academic researchers have been hot on the trail of the lost literary genre and popular art of Battala. Some College Street publishers have even started reprinting facsimile editions of Battala books kept in libraries in India and abroad.

Yesterday’s “filthy books” are today’s archival wealth.