“His Majesty Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar Padshah commanded,” so records Bayazid Bayat in 1587, “that any servants of court who had a taste for history should write.” His favourite aunt, Gulbadan, responded to the emperor’s exhortation and wrote a vivid memoir “of women on horseback, of women journeying and living in tents, and sharing the struggles and victories of their men”. Abul Fazl composed the monumental two-volume chronicle of Akbar’s reign, the Akbarnama, illuminated with brilliant miniatures painted by forty-nine artists, both Hindu and Muslim. Ira Mukhoty has a taste for history, and she can write. Her riveting narrative of Akbar’s life and times draws on the best historical scholarship while being accessible to a general readership. Reading both Abul Fazl’s eulogies and Badauni’s deprecations with a critical eye, she has produced a first-rate twenty-first century biography of a sixteenth-century monarch.

The emperor’s life extraordinaire unfolds chronologically in six phases. Mukhoty deftly sketches the Timurid heritage, Humayun’s courtship of Hamida Banu, memories of the moment of Akbar’s birth, an uncertain childhood as a refugee prince, and a grand circumcision ceremony in Kabul. Humayun’s tragic tumble down his library stairs in Delhi led to the hasty installation of the thirteen-year-old Akbar in 1556 as Padshah in Kalanaur, some 500 miles away by the river, Ravi. The foibles of youth during the early years of regency under Bairam Khan gave little indication of the emperor’s future greatness.

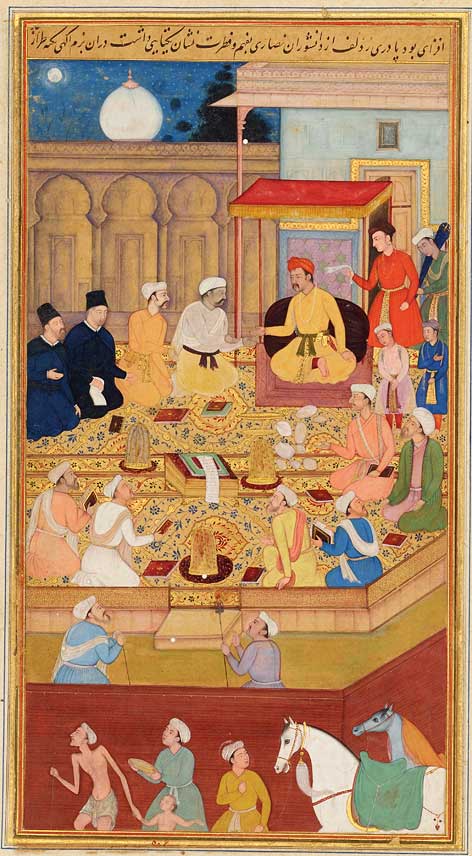

Akbar truly came into his own during the decade of the 1560s. His marriage to Harkha Bai of the Kachhwaha clan of Amer signaled the beginning of his alliance-building with Rajputs and drawing many of them into the mansabdari nobility. He abolished the discriminatory jizya tax. In 1562, he inducted the musical genius, Tansen Kalavant Gwaliyari, into his court. That same year, he commissioned the illustration of the Hamzanama. His tasvir khana, led initially by Mir Sayyid Ali and then Abd al-Samad, trained over a hundred Hindustani artists, among them many Hindus from Gujarat. The fifteen-year-long project eventually produced twelve volumes with 1,400 paintings in which “Persian delicacy and flat linear forms jostle with Hindustani vigor and exuberant color”. A polyphony of languages, ranging from Turki to Persian and Brajbhasha, animated Akbar’s court.

Akbar: The Great Mughal — The Definitive Biography by Ira Mukhoty, Aleph, Rs 799 Amazon

The 1570s witnessed some of Akbar’s key military expeditions. The conquest of Gujarat in 1572 gave the Mughal empire direct access to the vast trade of the Indian Ocean. Akbar astutely appointed Raja Todar Mal, the first diwan of the subah of Gujarat. Akbar’s voyage with his naval fleet down the Ganga in 1574 was the prelude to the defeat of the Afghans in Bengal by a Mughal force led by Munim Khan. But the turbulence in Bengal was not quelled until Raja Man Singh became subahdar in the 1590s. In 1575, the women of the royal household boarded the Salimi and the Ilahi in Surat to embark on an imperial haj.

It was after the 1573 victory in Gujarat that the prefix, Fatehpur, was added to the name of Sikri. This red sandstone capital built by Akbar reached the zenith of its intellectual and cultural efflorescence in the early 1580s. In its maktab khana, a team of talented linguists and writers began translating the Mahabharat from Sanskrit to Persian in 1582. The Razmnama (Book of War) was then transcribed in stunning calligraphy and illustrated with 168 paintings. Akbar engaged in discourses with theologians belonging to all known religious faiths and especially enjoyed the company of Jains and Jesuits. Literature, the fine arts, music and cuisine made Akbar’s capital a magical city. “Once all the lamps and candles were lit, the palaces and courtyards of Fatehpur Sikri would be ablaze with flickering light;” writes Mukhoty, “some of the candlesticks and wax candles were so tall that a ladder was needed to snuff them out.” One morning in the spring of 1583, Akbar rode out to rescue a young widow, a daughter of Udai Singh, who was being forced to commit sati. Four years later, he issued an order sanctioning widow remarriage. His solicitude for the welfare and well-being of women of all generations was an abiding commitment throughout his life. The birth of daughters was celebrated as joyfully in his court as the birth of sons.

“This city is second to none,” Monserrate had written of Lahore in 1582, “either in Asia or in Europe, with regard to size, population and wealth.” Akbar’s Lahore years from 1586 to 1598 added to the city’s lustre. The first Persian rendering of the Ramayan and its production as an illuminated manuscript was undertaken here. The death of Tansen in Lahore in 1589 seemed to Akbar to be “the annihilation of melody” but he ensured that the best musicians and dancers of the city gave him a joyous sendoff. The Mughal empire through its export of textiles had by now become a magnet for the inflow of vast quantities of silver. The quality of Akbari coins was “far superior” to those being manufactured in England under Elizabeth I. The 1590s saw the consolidation of Mughal suzerainty in Kashmir, Sind and the north-west frontier. The death of Birbal in the Yusufzai disaster of 1586 had shaken Akbar to his core, but now the borderlands seemed quiet. The Deccan campaigns had mixed results, but Man Singh ensured that the prosperity of the Bengal subah was beneficial to the empire as a whole.

Akbar’s final years brought him a lot of personal grief. Salim’s recalcitrance and rebellions from 1597 onwards, the assassination of Abul Fazl in 1602, the passing away of Gulbadan in 1603 and, finally, the death of his revered mother, Hamida Banu, in 1604, were body blows to the emperor. “A long aching lamentation” from the women’s quarters announced the death of Akbar on the night of October 26, 1605.

A man of many qualities and achievements, Akbar’s most profound legacy was his philosophy of ‘sulh kul’ or peace for all. He had envisioned, as Mukhoty puts it, “a horizon lit up by the light from many different faiths”. This timely book makes us ponder: will India plunge into darkness or rekindle that divine light?