At the young age of 20 when author Sarbpreet Singh left for the United States, he had no inclination towards his faith. However, over the course of the years, with maturity came a longing for home and the desire to know his roots. Extensive and in-depth reading and research, which involved teaching himself the Braj Bhasha, while managing the reigns of a billion-dollar company as senior vice president, Singh was drawn to the history of his faith and the atrocities of 1984. Since then, he has strived to express himself through his art that has included a long poem, Kultar’s Mime, narrating the stories of children who survived the pogrom of 1984 unleashed on Sikhs, which was later transformed into a play by him and his daughter, that ran in multiple cities around the world. Soon there was a best-selling book The Camel Merchant of Philadelphia and the stellar collection of short stories Night of the Restless Spirits that documented various slices of life during the ill-fated pogrom. A stray conversation with a young American in a gurdwara led to a podcast written and narrated by him called The Story of The Sikhs that is now heard in over 90 countries.

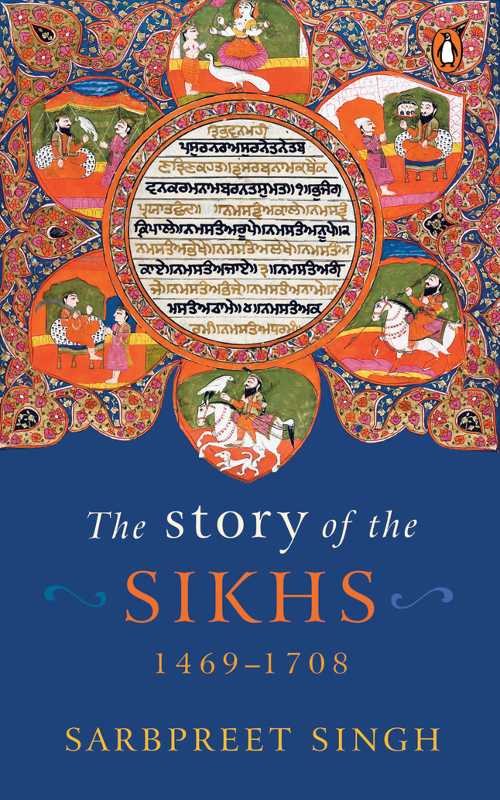

• It was only a matter of time before Singh realised the richly researched content that was available in the form of his podcast scripts that he could collate into a book and thus was born his latest offering, The Story of the Sikhs 1469 —1708 (Penguin India; Rs 999) narrating the tale of the Sikh gurus in beautiful and simple prose, inundated with his translated poetry in between.

“I couldn’t read Gurmukhi so I had to rely on the English language versions of Sikh history. My initial understanding came from a Scotsman, J.D. Cunningham, who wrote one of the first history of the Sikhs,” reflected Singh on a call with The Telegraph on the beginning of his journey with the Sikh faith. He also refers to Diana Eck’s The Pluralism Project that led him to meet some wonderful people and the eventual idea of a globally acclaimed podcast. Bhai Santokh Singh and his 14-volume literature on the Sikh gurus written in verse form in Braj formed the crux of this book that contains poems translated by the author himself. “His work wasn’t history from a historian’s point of view. It was pure rhetoric, poetry in its most beautiful form.”

• The driving force behind the book was the access of knowledge in a palatable form for the next generation. “Even within the Sikh world, there is a lot of knowledge about Guru Nanak and people know a fair bit about Guru Govind Singh as well, especially for his military exploits. Then people know a little about Guru Arjun and his sacrifice. How he was executed on Jehangir’s orders. The other gurus are not so well known, even among Sikhs. That was when I stumbled upon more text in Braj but mostly ballads and poetry,” he added.

The extensive effort put into research about the gurus to create the first two seasons of the podcast made for the perfect base material for the first draft of the book we now have in our hands. Singh claims to not be a historian and says that the book is more a work of literature than a book of history. “I have very much approached it as a storyteller,” he says, speaking extensively about the delightful and engaging historical work of William Dalrymple. Citing him as an inspiration for his writing style, the other driving force happened to be the dream of telling a story. “This story is mostly for young Sikhs who are searching for their roots like I was many years ago and for non-Sikhs who are looking to engage with faith,” he added.

• Western historians and even some Indian historians have dichotomised the Sikh gurus, in particular, Guru Gobind Singh and Guru Nanak. He refers to Guru Nanak’s image in popular art as an old bearded man with benevolent eyes and a hand raised in benediction and what we learn about him as a man of peace who fought for social justice. Whereas Guru Gobind Singh is seen as a young and dynamic warrior with a black beard and bearing arms fighting for peace. “However, history discounts the commonalities of their experiences and what gets lost in this dichotomy is the startling unity of thought,” he says.

• The author is clear about the impossibility of writing a religious text by separating it from their politics. “The Sikh gurus were not ascetics. They didn’t live in the forest and they were men of society. Guru Nanak settled in Kartarpur and became a farmer after his wanderings. Being connected to society, being a man of family, having children, worrying about what was going on around you, preventing discrimination of any kind, be it caste, gender, race, made them who they were. I would call them ‘men of the world’”, says Singh. While men before him had opposed caste discrimination, Guru Nanak devised institutions that enabled the dismantling of such system –– the langar, for instance, which compels people to sit on the same floor and share the same meal not knowing the caste of your companions. “His langar was perhaps a political act in the same way as Guru Arjun’s decision to not pay Jehangir’s fine or Guru Hargovind’s raising of an army and actively fighting the Mughals, was. They fought for righteousness” he affirms.

• A conversation with Sarbpreet Singh is always engaging, educative and enlightening and this time was no different. Reading through his meticulously researched and wonderfully imagined lives of the Sikh gurus validated the popularity of his podcast –– two projects born from sincerity of thought and action. For a generation increasingly disillusioned by the idea of religion to the point of denouncing it due to active communal manipulation in the name of political clout, this book comes at a time when re-enforcing of faith is of utmost value, making it to our ‘must-read’ shelves.