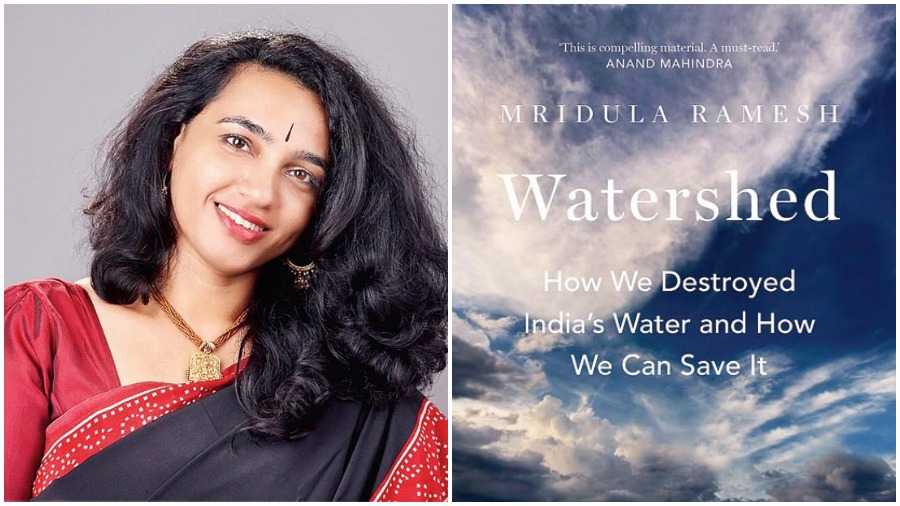

Mridula Ramesh ran out of water in her home in Madurai and that singular incident gave rise to a chain of actions that has now led us to a definitive book on the water crisis in India –– Watershed: How We Destroyed India’s Water and How We Can Save It (Hachette India; Rs 699). Her now zero-waste home is a symbol of possibilities for a world that stands on the precipice of crisis. The Cornell University graduate and a post-graduate teacher of climate change at Great Lakes Management Institute, Ramesh leads her own Sundaram Climate Institute working extensively with waste and water management. A burst of positivity, Ramesh takes ownership of the problems we face and provides cohesive solutions for the same. With immense faith in individual responsibility, she said during a recent conversation with The Telegraph: “Conscious customers are going to drive real change in every industry that we speak of.” Investing heavily in start-ups that are working towards a conscious future with conservation at their helm, her work is largely based upon data. Here are excerpts from our riveting conversation.

Tell us about the inception of this book.

After that incident, normally one would just move past the situation, right? But this time I had just had a child and I had time off. That got me thinking and trying to put the pieces together why anyone wasn’t talking about this subject. The answer to that question –– why isn’t anyone talking about this –– and what can we do about it, led to the first book, The Climate Solution: India’s Climate-Change Crisis and What We Can Do About It. After the first book, as I started getting more and more plugged into conversations around climate change I realised that most people when they talk of climate change, talk about carbon. One has to get their carbon emissions down and I totally agree, that’s very important. But the climate itself talks in the language of water. You see that in the rising crescendo of storms and floods. Water needs to be a part of the conversation. So this book is a direct result of that.

Since you mentioned your first book, what was your reaction to the wonderful critical reception that it received?

I am very grateful and my English teacher from school wrote to me saying that she is proud of me. But jokes aside, most of the conversation has been through letters I have received from readers from all walks of life. They said that they go back to the book every day. If they want to fix something, they refer to it.

The role of an individual in climate change is often debated with the argument leaning towards policy-level changes for any marked difference. Where do you stand on this scale?

That’s a great question but the real question here is who makes policy? In my previous book there is a small section, written like a play in three parts, which indirectly spoke of policy and said that it won’t make a difference. I got a lot of pushback for it. So this time, in my institute I spoke to 900-plus people asking if they would vote on water or waste. I’m not going to sit in an ivory tower and opine that people care about this. I actually asked people from all walks of life –– auto drivers, domestic help, shopkeepers –– a wide spectrum of people, in the middle of a drought. And the short answer, which I’ve put in my book is: ‘No’! There is this data collected from just one city but there is also rich data coming in from across India by other water surveys and there are lessons in policy-making across the decades in India.

And if politicians find that those policies don’t get them re-elected, they’re not going to make it again. So it’s easy to say let’s push it on policy.

Will good policy make a difference? Of course, it will. I am a pragmatist and I understand the likelihood of that happening. And that’s why I say decentralised policy will make a difference. It’d be wonderful if America could wake up one day, find enlightenment and put a carbon tax or a carbon dividend. It’s been 40 years since everything came out and emissions have only gone up. We chose to become independent when we ran out of water and every story in this book and the previous one is of real people. That sort of resonates with the way India operated before. It was de-centralized with communities taking ownership saying it’s our responsibility. The climate is menacing and it’s got talons, but we’ve got armours too. So if we’ve just thrown away or destroyed our armour, that’s on us and that’s something that only the communities can fix. So, yes, policy can be a wonderful and powerful tool but I won’t hold my breath for it to happen.

What are the lessons that urban-dwellers have to learn from this community-building that we can adapt into our ecosystem to better ourselves?

That is something that is happening in Jakkur lake in Bangalore. There is an NGO that decided to take it up and work with the municipal body, taking up the maintenance of the lake. The idea is to make the tank the centre of the community again. One has to find ways to make the tank a catalyst. One has to create places for people to congregate, take a walk and enjoy the air. One of our associates even thought of Wi-Fi-enabled selfie spots to attract the youngsters. Boating, playgrounds, good food stores, performance spaces –– they all make for a fantastic experience.

Could you tell us a little about the kind of work that happens in your Sundaram Climate Institute?

We are a tiny institute with a fierce belief in data. Waste and water are our two pillars. We believe that global warming has already crossed certain thresholds and India needs to adapt. We look at waste management, which is surprisingly an easy thing to do. One of the things we look at is solutions by making things easier for you. But we also look at attitudes. We have two flagship studies and one of them has been going on for three-plus years. It involves talking to over 2,000 households and finding out their lived reality of water. One can’t just say India has a crisis, it’s not a monochromatic crisis. For the rich, water is peripheral. In the middle, the water crisis is one of uncertainty which only gets worse as you go down the socioeconomic ladder –– it’s heartbreaking. The kinds of compromises that we’ve found that our respondents have had to make is just sickening. One of the second aspects is the study of tanks. One of the things we found is, as long as you have a tank, or a lake nearby, you’re far better off. So many people buy water. And I think 40 per cent in our survey, across the income spectrum, buy water. We try to say, let’s understand the reality and then let’s try and figure out what will work in this very real set. So no, no rose-tinted glasses!