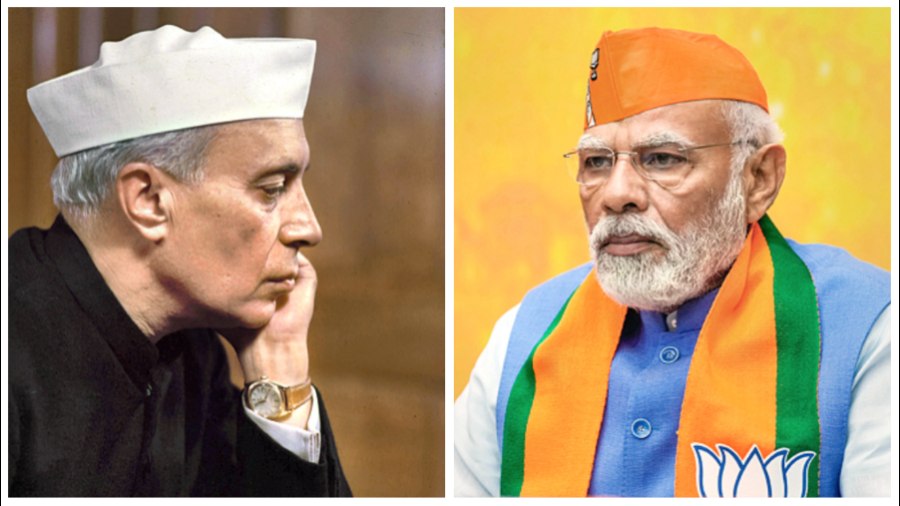

Book: India’s Economy From Nehru To Modi: A Brief History

Author: Pulapre Balakrishnan

Publisher: Permanent Black/Ashoka University

Price: ₹895

Pulapre Balakrishnan presents a balanced assessment of India’s economic policies and performances since Independence. He analyses the Nehruvian era from 1947 to 1964, followed by what he calls the “watershed years” from 1965 to 1990. Then he covers the period of economic reforms from 1991 to 2013 and, finally, the Narendra Modi years from 2014 onwards. Balakrishnan asserts that the founding fathers, especially Jawaharlal Nehru, envisioned India’s Independence as leading to an expansion of freedoms for its citizens, both positive as well as negative freedoms. He draws on Isaiah Berlin’s famous distinction between the two concepts. Negative freedom implies the restraint shown by the State in not interfering in a citizen’s life. Positive freedom, on the other hand, allows the citizen to choose the things he/ she wants to do in life. This idea is drawn from Amartya Sen’s concept of development as an expansion of positive freedoms. Balakrishnan’s interpretation of India’s economic history of the last 75 years takes place through this lens of freedom. He concludes that despite many far-reaching changes in the economy, the nation has experienced adequate human development. This ‘Senian’ reading of India’s recent history is rather rare in the literature on the subject.

The author comes to some significant conclusions based on data as well as inferences drawn from political events. The Nehruvian era of planning ought to be viewed in the context of the times. There was very little room for anything else in a world of weak, local capital and a desperately poor agriculture sector. Balakrishnan makes an important distinction, claiming that Nehru was more concerned with large investments mobilised in the capital goods sector of the economy than with the idea of a public sector making those investments. Over and above the well-documented criticisms of economic planning in India, the author points out that Nehru could have invested decisively in basic education in a country with very low literacy rates. He chose not to. However, he did invest in secondary and higher technical education by allowing the creation of the IITs and the IIMs. During the 1970s, Indira Gandhi took India’s polity and economy leftwards with a spate of nationalisations and the declaration of the Emergency. In the turbulent decade of political and economic uncertainties, private investors froze and held back expenditure in capital formation. The Indira Gandhi of the 1980s during her second stint in power was a different political creature altogether, being very corporate-friendly. This trend was carried on by her son till the end of the decade. A gradual injection of liberalisation with a strong dose of technological enablement allowed investments to return and growth to inch up quickly.

Then came the famous economic reforms triggered by political compulsions and economic crises. The policy changes accelerated private investments and, gradually, India’s economic growth rate began to climb. However, despite these changes in policies, the lack of adequate public investments in developing human capabilities, changing the structure of Indian agriculture and creating business-friendly physical infrastructure continued to put a burden on the nation’s economic development in the 21st century.

The Modi era brought a new type of politics — the aim of building a new India which put political and cultural issues ahead of crucial economic ones. Political ideology came to the fore, once again, as in the first decade of Indira Gandhi. Only this time, it was quite right-of-centre than left. The shock-and-awe policies of Modi, such as demonetisation, have frozen Indian investors. That, and the massive shock of the pandemic, left the economy in turbulence. Growth has slowed down, poverty and inequality have been rising, the informal sector has been left in the lurch, and public investments are not increasing enough — these have left the economy on the edge. There has also been a sharp increase in foreign direct investment leading to a larger foreign presence in the economy.

Balakrishnan is of the opinion that the Modi government continues to be enamoured of the Washington Consensus of the1980s and 1990s, long after it had gone out of fashion in the developed countries. Hence, independent of current requirements, the policymakers have been overly concerned with fiscal consolidation and inflation targeting. The inevitable conclusion emerges: much has changed successfully, but some things fundamental have not, and they continue to heavily weigh down India’s economic development.

This final assessment is not new at all. But reading Balakrishnan’s book, one gets the feeling that those who control the economy — policymakers, the political class and big capital — have done remarkably well in 75 years. They achieved what they wanted to in terms of material wealth and freedoms. But does anyone really care about the remaining 80 percent of India?