Book: Love and Sex in the Time of Plague: A Decameron Renaissance

Author: Guido Ruggiero

Publisher: Harvard,

Price: £39.95

At first glance, Love and Sex in the Time of Plague by Guido Ruggiero looks like a re-evaluation of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, set in 1348; yet, nowadays, any word in the title that denotes an epidemic makes us itch to read the work. One may call it a Pavlovian conditioning by this point.

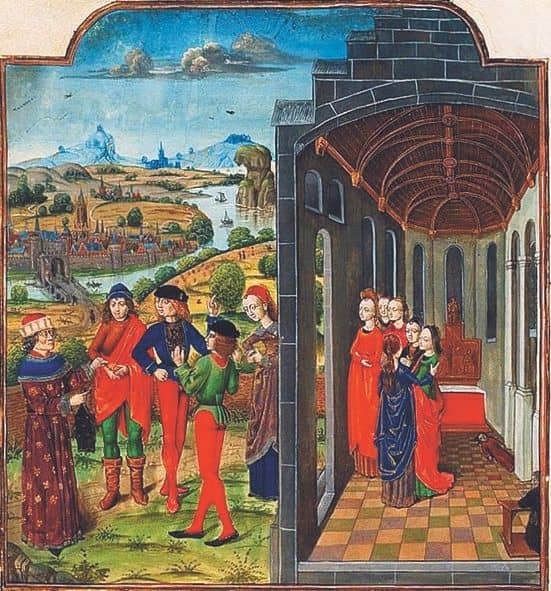

Ruggiero mentions the plague that devastated Europe only incidentally. His interpretation is more focused on Decameron, and the significance of its tales. The text goes like this: in 1348, seven women and three men escape the city of Florence to take shelter in a villa in the hills, where they have servants, gardens, and other comforts to make them forget that their city is being destroyed by the plague. To entertain themselves, each tells ten stories dealing with marriage, sex, infidelity and love, and they certainly do not waste their time discussing the current epidemic.

The text seems to suggest that both the stories and the act of their telling are outcomes of the changing world of Renaissance Italy, especially northern Italy. Ruggiero explains how the nobility was gradually losing its previously unchallenged power, and actual governance was being taken over by people who were neither royal, nor noble. The socio-religious power tussle with the clergy that sustained the rule of the nobility was also being slowly edged out. The economy was evolving into something more complex than traditional societal norms could accommodate. The new governments had new laws that restricted and controlled the nobles to some extent. The plague threw all of the above mentioned transitions in relief. The stories of Decameron were being told in the middle of this transformation.

The book is divided into five parts by theme — Laughter, Violence, Sorrow, Transcendence and Power. In each section, he cites tales from Decameron to discuss the aforementioned changes, and zeroes in on the much-contested concept of virtù to do so. Virtù was a quality men sought, and expected to acquire, that would provide them with eminence and value. Ruggiero has discussed the manifestation of virtù in his other writings as well, but here he talks about how the concepts of marriage, sex and love were evolving at the time, and how virtù was instrumental in the process. One such example he uses is the story of King Agilulf and his queen, who was misled into thinking that a servant who had snuck into her bed under the cover of darkness was the king. Agilulf learns of it, but suppresses his desire for vengeance, so that his marriage continues to be stable and his renown as a ruler remains honourable. The ability to develop and maintain this attitude is called virtù by Ruggiero in this case, but he goes on to say “the prince demonstrated his wisdom (virtù) as a ruler, and the groom survived his lovesickness thanks to his own cleverness (virtù).” Elsewhere, Ruggiero cites the tale of Ghismonda: “[s]tatus, she claimed, should not be based on the traditional standards of nobility — birth and blood given by fortune — but on newer behavioral models that turned on reason, manners, and the ability to get things done — in sum, the familiar attributes of upper-class virtù.” So just as the nobility could keep its position by demonstrating virtù — the judicious use of strategy and practical wisdom — the non-nobility could also work its way up the social ladder by amassing virtù. Ruggiero argues that this re-assigning of virtù was becoming an apparatus of said change, and that virtù became a standard for assessment for all classes, not just the nobility.

He proposes that these one hundred tales be re-read as historical documents, or at least documents that comment on their contemporary world and, in doing so, help create a particular aspect of the phenomenon we now know as the Renaissance: “how they contributed in a foundational way ultimately to the birth of a more general European renaissance and perhaps to visions of marriage, love, and sexuality that still underpin Western notions that are central to our shared culture today”. Informed readers might reflect that the changed notions marked a growth of humanity, but perhaps Ruggiero is hinting at changing roles (perhaps changing, once again, during the current crisis) and not a change in fundamental nature. Even then, the proposition and the history behind it are fascinating.

The itch we brought up in the first line is not addressed straight up either in Boccaccio or in Ruggiero. That disappoints us, for we are looking for a set of instructions that will lead us out of our current demoralized state. What we do get is a map of the constellations that can help us navigate our dark waters. Whether the reader acquires a compass of virtù, Boccaccio did not foretell; and Ruggiero, the astute historian and academic that he is, leaves it at that.