Book: Un/Common Schooling: Educational Experiments In Twentieth-Century India

Author: Janaki Nair

Publisher: Orient Blackswan

Price: ₹1,145

It is not easy to review an edited volume of uniformly excellent essays on a subject that remains crucially relevant for our present times. The volume grew out of two intersecting academic initiatives — an oral history project of practitioners and advocates of alternative education and a workshop on education and the challenges that it encountered in the post-Independence context continuing into our present. As a result of this productive intersection, the volume has the rare distinction of presenting an archive of voices as well as providing a reflection of the initiatives that were attempted in the field of alternative, supplementary and informal education.

Backed by a lucid introduction that grapples with issues of definition of alternative education and delineates its brief history in changing contexts — the colonial and the post-colonial — it persuades the reader to reflect on the challenges that we continue to face in terms of access, equity and content as far as school education and its pedagogic content is concerned. What makes the volume especially appealing and valuable is the perspective that it provides from the vantage point of both those who were at the forefront of new and uncommon pedagogic initiatives as well as those who experienced the programmes. Practitioners interacting with children, learning to negotiate social and sociological constraints, adopting real-life inputs to make education an inclusive practice come alive in this volume, making it a must-read for anyone invested in the practice of learning and sharing the same with a wider constituency.

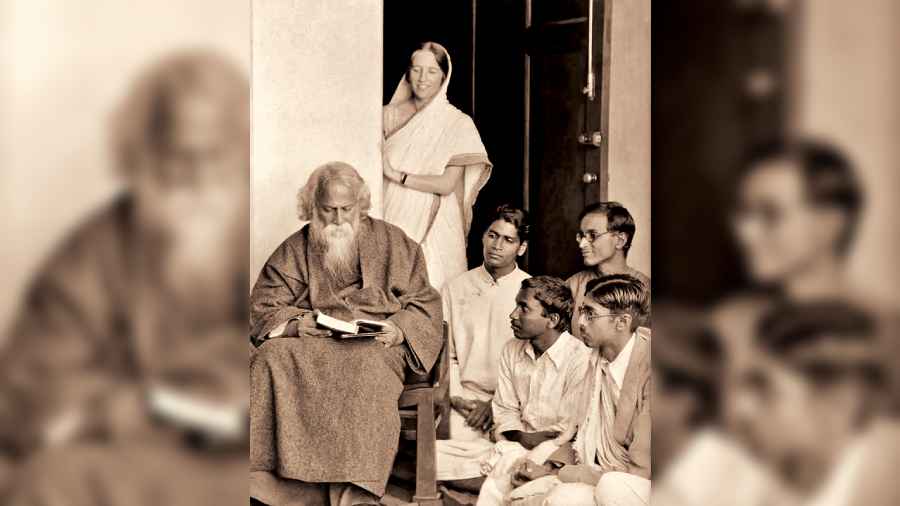

The book is divided into three parts. Parts I and III describe schools set up under different programmes and, in the process, probe the differential impact of schooling on individual lives reconstructed through a range of narratives. Part II of the book looks at historical and contemporary experiments in rural education. Rabindranath Tagore’s rural education and reconstruction programme is analysed in some detail and we have a fascinating exploration of the poet’s worldview on a holistic education that was not concerned with the production of binaries such as rural and urban but sought to go beyond them. P.K. Datta introduces the idea of embeddedness in the ways Tagore conceptualised both Visva-Bharati and Sriniketan wherein the emphasis was on action and life skills that would foster confidence and self-sufficiency. The essays that follow — the one on the Vikasana school established by M.C. Malathi and Kanavu by Shirley Joseph — speak of the same drive, vision and imagination and, sadly enough, of failure, prompting the question why individual initiatives do not resonate with the larger collective structures of power and aspiration.

What lifts the volume is its seamless integration of concepts such as the economy of care with the actual experience of thinking differently about schools, care and pedagogic content. The challenges of setting up schools in rural areas, finding children to participate in them, and overcoming parental resistance to alternative schooling make for fascinating reading. It is, in fact, difficult to single out any essay for a detailed commentary. I choose the essay on Eklayva partly because it shows up the complexities of the social context better than most and reveals important dimensions of the pedagogic debate. Arising out of the need to teach science and eventually a range of social science subjects, it achieved impressive outcomes until the 1990s. It was then that contestations over its curriculum ensued, leading to its eventual scrapping and making it available for larger numbers of government schools. The contestation brought home the vulnerability of the stakeholders in the project and the rapidly diminishing space for any critique of government decisions. On the other hand, the essay also acknowledges the lessons learnt from the experience and holds out hope for the future. The volume is a testimony to those who ceaselessly work for the larger and disempowered segments of society and to the idea that alternative education is crucial for revitalising society at the grassroots. It is inspirational in its simplicity of tone and style and profound in its documentation of individual and collective effort.