Hong Kong, 1993. The newspaper habit never really leaves us Indians. And so it was that the South China Morning Post announcement of a book signing at its Star Ferry bookstore by Jan Morris was a sign to drop all other touristy activity, including a steep tram ride to The Peak, to meet this author extraordinaire. Who, as an intrepid journalist, known in those early years as James Morris, was privy to the scaling of the world’s highest peak, Mount Everest, scooped the story to The Times in guarded language, and the result was a historic exclusive that teamed in well with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. That was then. A heady historic moment captured on camera with a slim, young man of 26, shaking hands with the conqueror of Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing next to him.

Many avatars followed. From soldier to wartime journalist, to rich chronicler of Empire — the seminal Pax Britannica trilogy, the 40 books, amongst them on varied places like Venice, Oxford, Spain, Wales, Manhattan — where she trawled the depths of their souls through her tractable-travel spin; and along the way married her companion Elizabeth for life, fathering five children and then, most boldly penned and discussed in Conundrum, her gender change. The quality of writing and of her living appeared to have got even better after this.

And so, there we were, at Star Pier, facing the gargantuan persona of Jan Morris. A large woman in her physique, and larger than life in her prodigious writings. Awed, naturally, gawking at this stately figure with a mop of snowy white curls, but quickly put at ease with her warm, if powerful presence. The book in focus was Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire and if one was looking for a part-historic and semi-travelogue tome, it was not to be. It was irreverent, steeped no doubt in her deep understanding of British hegemony, bringing out the chaos, the “brazen embodiment of free enterprise”, its palpable aura of money, all the while focusing on the Chinese adaptability to western culture, with foreigners and Chinese sharing the uppermost ranks of business and finance, the contrasts between westernised appearance and oriental reality, with the “clatter of mah-jong” being a more common sound than the ping of electronic games.

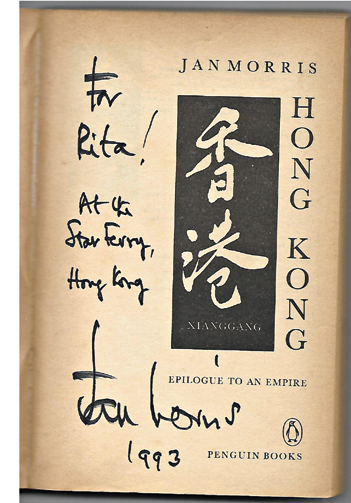

Hand written note by Jan Morris for Rita Bhimani Sourced by the correspondent

A blurb on the book talked about how, by “combining firsthand reportage with exemplary research, Morris takes us from Hong Kong’s clamorous back alleys to the luxurious Happy Valley racecourse, where taipans place their bets between sips of champagne and bird’s nest soup. Morris chronicles the exploits of opium traders and pirates, colonists and financiers, and shows how their descendants view the prospect of reunification with the Chinese mainland. What emerges is an epic tableau, vastly informed and pungently evocative.”

One was yet to get into the book, which on later reading showed the serendipitous early days of Hong Kong as a “small, hilly treeless granite island... shaped like a multi-clawed and corrugated crab”, the “remote and inconsequential territory”, to “what the West has provided, originally through the medium of the British empire, later by the agency of international finance, a city-state in its own image, overlaying the resilient and homely Chinese style with an aesthetic far more aggressive.”

But at the Star Ferry, I could not get Wales out of my immediate focus — and Morris’ Welshness is what she savoured — so there I was trying to tease out rare bits, Welsh musicality, regurgitating how she kept the music on in the house up and running even when she would leave home; and did she know Tony Lewis, the once England cricket captain, whom we had met many times on our cricketing travels and who was promoting his native Wales as the Tourist Board chairman and his musical proclivities. An approving resounding yes from her about Tony and a quietly tucked in invite to visit her and Elizabeth, when next in the north of Wales, Llanystumdwy, which is somewhat of a cultural hub. Language could sort itself out if we ever made it there.

And when asked why there had never been a travelogue on Calcutta, the humorous eyes twinkled and a diplomatically hinted phrase in effect said there would be world enough and time. For someone obsessed with Empire, a robust historiographer, we could only hope that for a person then in her mid-sixties, it would materialise.

Jan Morris did say, though, that she would be making time to get back to her Hong Kong world returning to Chinese rule in 1997, “towards a more modern and liberal condition”, perhaps, and she had booked herself a hotel room in advance that was being offered at Hong Kong dollars 1997.

Sadly, having had no cell phones of today’s ilk, there are no pictures to show for it. Only memories. And an inscribed book. By an extraordinary historian, novelist, author of an imagined city-state Hav, a biography of the British naval reformer John Arbuthnot Fisher, with whom she would have liked an affair, a writer who made travel tomes less mapped of territory and more people and personality inclusive, and whose posthumous work with its working title ‘Allegorizings’ promises to reveal many personal reflections.

The author is a public relations veteran