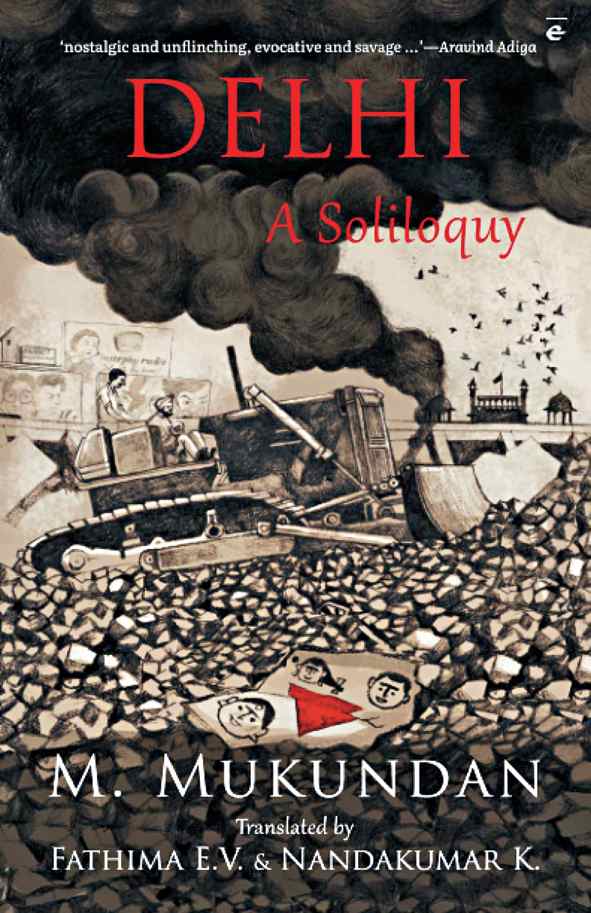

Author M. Mukundan’s translated work Delhi: a Soliloquy (Westland) won the prestigious JCB Prize for Literature a fortnight back. The prestigious award that was constituted in 2018 involves a winning amount of Rs 25 lakhs with an additional Rs 10 lakhs for the translator if the winning novel happens to be a translation. With Mukundan, the two winning translators for Delhi: A Soliloquy were Fathima E.V. and Nandakumar K.,who worked on this book that was originally written in Malayalam. The jury for this award in 2021 included Sara Rai, Annapurna Garimella, Shahnaz Habib, Prem Panicker, and Amit Varma.

Narrating the tale of Sahadevan, a young man of Malayali origin who makes Delhi his home in the 1960s, this book is an intimate and fiery look at a city and a country on the brink of war and its debilitating effects on the citizens. A culturally rich and intimate text, Mukundan’s book was unanimously voted for by the judges, opening up further conversations on the need for translations and their importance in today’s times. JCB Prize for Literature has always paid equal attention to works of literature written in English as well as translations. We spoke to the winner and the director of the festival, Mita Kapur, on winning the prize and conducting a national award of great repute in the middle of a pandemic. Excerpts...

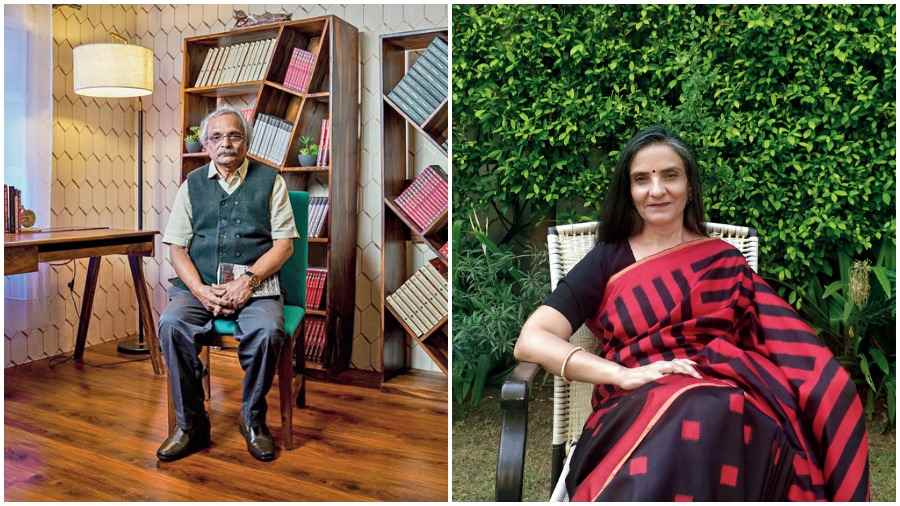

M. Mukundan, winner, JCB Prize 2021

How does it feel to have won one of the largest literary awards in the country — The JCB Prize 2021 — right now?

All writers long for the JCB Prize and only one is lucky to have it. I am delighted I am the chosen one. Winning this award has raised my status from a regional writer to a national writer. It is a nice feeling. My readers in Kerala are also very happy about it. This is a precious moment in my writing career, which I will always cherish.

Having written over decades, do you feel that translations are finally getting their due importance?

In Malayalam literature, we have always had excellent writers, but not enough good translators. So most writers found it impossible to transcend the borders of language and reach out to wider readership yonder. There’s now a shift in this scenario. Excellent translators are coming to the rescue of writers and, through their wonderful translations, helping them to take their works to the vast English-speaking readership. As for their part, big publishers like Westland who published my award-winning novel, are willing to bring out translations.

Having won so many accolades, do you think your emotional equation with awards has evolved over the years?

When I receive even a small award I feel elated. I believe that all awards, irrespective of their size, enlarge my readership. A literary prize is an invitation to the readers to read the award-winning author’s works.

Looking back, what would you consider three literary milestones in your career?

The writing of two novels — On the Banks of the Mayyazhi River and Delhi Gathakal (Delhi: a Soliloquy ) — is for sure the first milestone. I started writing in the Sixties. Since then a large number of readers follow me, making me one of the bestselling authors in Kerala. Their number has never dwindled. I consider this as another achievement. And the third one is no doubt winning the JCB Prize.

What would be your words of advice for young writers keen on writing in one of the many Indian languages?

Just because you write in an Indian language, don’t feel that you are inferior to those writing in English. Indian language fiction is getting noticed beyond the borders of our languages. Write well, get your works rendered in English, and win the JCB Literature Prize! Then you can fly. This is my modest advice to young writers of Indian languages.

Are you working on something currently? What can we expect next?

Right now I’m working on a novel on euthanasia. It is not legally allowed in India. But in fiction, everything is allowed. Novelists frame their constitution. I hope India will give legal sanction to the practice of euthanasia, thus putting an end to the sufferings of many. With this novel, I would like to launch a campaign for allowing mercy killing in our country.

Mita Kapur, Literacy Director, JCB Prize

Tell us about the experience of being a literary award director in a pandemic?

The pandemic made us realign a lot of our plans. It was a test in resilience and the decision to continue working, sticking to the Prize calendar made us think on our feet, pay attention to each detail. It threw up new opportunities and we seized them. Books are what people turned to for comfort, escape to find hope — the JCB Prize only continued to further that faith.

JCB Prize’s focus on translations is commendable — tell us your thoughts behind the same.

The Prize does give a lot of importance to ensure that more and more stories from all corners of the country reach as many readers and for that translations make a huge contribution. Each year, the number of entries of translations from different languages, many more states are increasing and that is a sure enough signal that stories in different languages are becoming increasingly accessible for consumption.

Tell us about the process of curating the longlist for the award. What are the few things that are kept on high priority?

The jury for each year reads, re-reads, discusses and debates all the qualifying entries that are sent in by publishers. The jury meets and decides what they are looking for — the common denominator is simply excellence in storytelling.

What did you feel was different about the JCB Prize this year in terms of submissions received? Any recent trends that you have observed?

We did see an increase in the number of submissions and from publishers placed in different corners of India, which was rather heartening to see. Authors have experimented with genre and robust voices. Overall, it’s been a time for growth and expansion in all senses.

How do you arrive at the jury panel every year?

All I can say is that they need to be voracious readers.

What are a few long-term goals for JCB Prize for Literature?

There has been a steady incline in the perception of what the JCB Prize has set out to do. Words like inclusivity, representativeness are not used as jargon here — the Prize walks the talk. The Prize is moving towards creating new and larger readership, knowing and understanding what India loves to read, pushing for more languages to come forward in translations. A treasure of stories is waiting to be discovered from all regions of India and the Prize intends to unearth them.

What are you reading and absolutely loving this year?

Completely immersed in Nosedive by Harold McGee and Elif Shafak’s The Island of Missing Tree