Book: The Greatest Invention: A History Of The World In Nine Mysterious Scripts

Author: Silvia Ferrara

Publisher: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Price: $29

The year is 1900 BCE. In the inhospitable desert of the Sinai Peninsula, the Egyptians have set up an outpost for mining turquoise. Here they work alongside labourers from the Nile Delta who speak a Northwest Semitic dialect called Canaanite. Hathor, the goddess of turquoise, protects them all, irrespective of the tongue they speak, and on rocks and statuettes that line the path to her temple, these workers carve some forty signs. The inscriptions make use of Egyptian hieroglyphs to record the Canaanite dialect, forcing phonetic adaptation. Among them, we find glyphs depicting the head of an ox, a house, and a stick: alp, bayt, and giml, giving us the ‘Abgad’ sequence of letters, which later “learns to speak hundreds of languages” across the world. Despite its popularity, Silvia Ferrara reminds us the alphabet is only one of many writing systems invented through time.

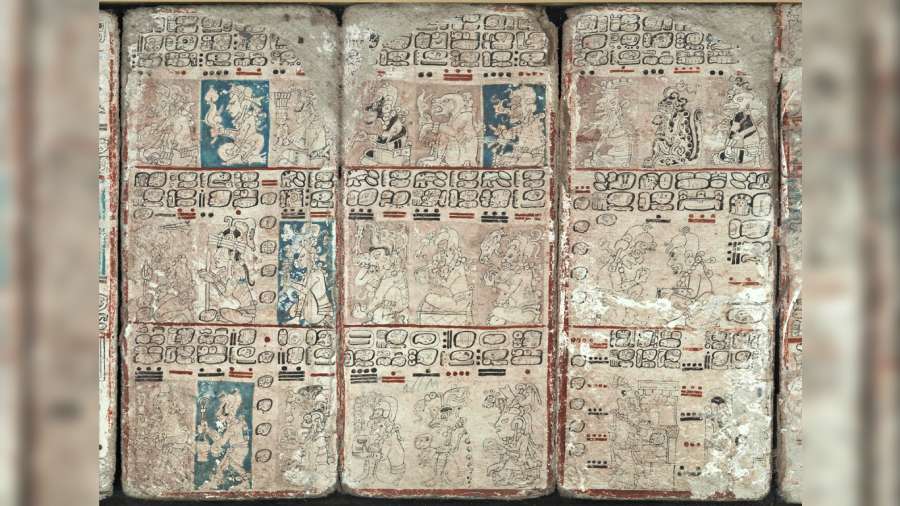

The Greatest Invention reads like a guided tour across space, time, research, and theory as Ferrara weaves together astonishing stories of human ingenuity — both of the magical ‘invention’ of scripts and of their deciphering. The stories of inventions are divided into two arcs: the first set on islands (Crete, Cyprus, and Rapa Nui or Easter Island), and the second associated with cities and empires (Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica). Ferrara conjures up a variegated collage of drawings, icons, letters, and syllables, interspersed with rigorous arguments (such as why Egyptian hieroglyphs challenge the established notion that cuneiforms are the first script invented by humans).

From Rongorongo, the syllabic script of Rapa Nui, to the 3200-yearold turtle-shell inscriptions from Anyang in northeast-central China, they reflect varying levels of success in decoding. She brings to life with equal verve figures like Fu Hao (d. 1200 BCE), the writing-pioneer, queen and advisor to Wu Ding of the Shang dynasty, and more recent eccentrics in the field of linguistics like Yuri Knorozov (1922-1999), who helped decipher the Mayan script, or Alice Kober (1906-1950), who recorded breakthroughs in reading the Mycenaean Linear B in her Lucky Strike cartons.

A third arc tells the story of “solitary inventors”, like the abbess Hildegard of Bingen, who in the twelfth century CE had invented a script with twenty-three signs to record secrets revealed to her in fantastic visions (caused by migraine according to Oliver Sacks); or the apparently illiterate Sequoyah (1770-1843), who invented a script for the Cherokee language, inspired by the ‘talking leaves’ of the EuropeanAmerican settlers. These narratives are framed by a rich conceptual apparatus. Without being pedantic, Ferrara, a scholar of archaeology and writing systems, suggests definitions of key concepts like that of syllables, icons, and lines, provoking introspection. And, based on her own research and experience, she offers an accessible and rigorous entry point into the ethical and methodological concerns of her field.

I do have two-and-a-half gripes with the book. In the postscript, Ferrara mentions that her style is experimental — written as if she were speaking to her audience about the things she has studied throughout her career. This works for the most part, allowing her to explore different tones such as suspense, the comic, reportage and, occasionally, philosophical, but it does not make for a uniformly easy read. At times, I had to spend time disentangling metaphors intended to represent and simplify complex arguments; for example, the use of a Moviola projection to explain the evolution of Mesopotamian cuneiform, before arriving at the concept, which itself can be difficult (albeit rewarding) to grasp. Perhaps these work better in the original Italian.

Secondly, while the book has its fair share of pop culture references, I found some tangential allusions to luminaries of the Western tradition somewhat burdensome. (Why does it have to be “a vague, Proustian memory” of learning about cuneiform in school, rather than a regular memory?) Not to be flippant: references that feel unnecessary and signpost a particular cultural topography can potentially alienate readers who are not as taken with the same tradition. And finally, it is a bit disappointing to find the singular masculine pronoun describing a hypothetical inventor (“working his clay, taking his stylus in his hand”).

That said, The Greatest Invention is a remarkable work that does more than narrate a history of the world: it leaves the reader with questions about writing, images, and languages, which will, hopefully, keep nagging at us as we engage with everyday practices and with our pasts. Expertly balancing historical accounts, myths, academic and philosophical insights, Ferrara undertakes the challenge of presenting the uninitiated with both a panoramic view of the field and contemporary open-ended debates without compromising on nuance.