Book: Mansions of the Moon

Author: Shyam Selvadurai

Publication: Penguin

Price: Rs 599

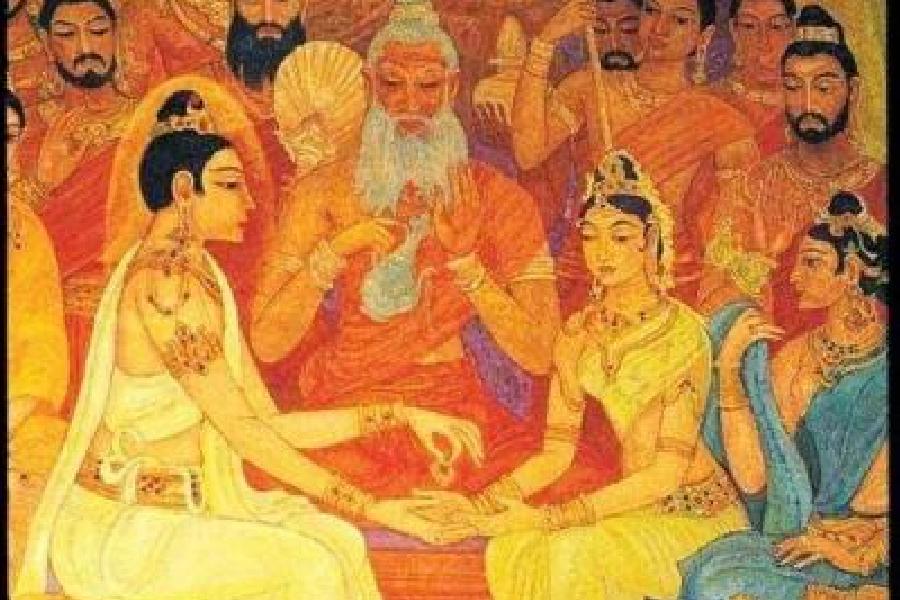

Inscribing an ancient legend in a contemporary form, Shyam Selvadurai’s new novel ‘realistically’ tells the story of Yasodhara, the wife of the Buddha. Nicknamed Ushas after the Goddess of Dawn and married to her first cousin, Surya/Siddhartha, at the age of sixteen, the novel chronicles Yasodhara’s journey down the river of life, covering her childhood, marriage, motherhood and, finally, her life as a bhikkhuni. While the novel form lends interiority to Yasodhara’s thoughts and feelings, the Buddhist concept of existence, ‘dukkha’, anchors the interior tale to the themes of impermanence and loss. Undoubtedly, Selvadurai is not the first to retell Yasodhara’s story, but his blending of the ancient with the modern in a realist form offers a fresh perspective on a well-known theme.

Canonically, Yasodhara is remembered as Rahula’s mother who held an iconic presence in the great renunciation scene, where Siddhartha renounced his wife and son, and who later became a bhikkhuni. Interestingly, in the medieval Sinhala tradition, these fleeting and fragmentary glimpses coalesced into a ‘story’, possibly to give coherence to Yasodhara’s exceptional devotion. However, in the secular traditions of 18th and 19th centuries, Yasodhara’s lament gained importance and was popularised as a folk poem, “Yasodharavata”, which generations of Sri Lankans heard and transmitted. Hence, Selvadurai’s intent in recreating Yasodhara’s life actively engages with the canonical and the Sinhala folk receptions of the Buddha’s wife.

In the Introduction, Selvadurai emphasises that Yasodhara’s life best illustrates the Buddhist tenets of transience and change. However, since the tale is framed within the larger story of the Buddha’s renunciation, there is an inherent — perhaps a structural — difficulty in interiorising Yasodhara’s narrative of losses, of “abandonment by those we love”, as it can potentially overshadow the enlightened and compassionate biography of the Buddha. Because neither Siddhartha nor the Buddha are oppressors, the patriarchal imperatives underlying the recreation of Yasodhara’s lamentation pose a novelistic challenge. How can one cut this Gordian Knot? Selvadurai offers some innovative ways out of this impasse. He chooses not to tell an individualist tale, but a densely peopled story. In sync with the style of social realism, Mansions of the Moon offers a tapestry of human relationships, of emotions and desires, along with intrigues of statecraft and diplomacy. Moreover, its epic canvas accommodates numerous characters, including Yasodhara, Siddhartha, Rahula and Ananda.

Within this realist mode, the theme of transience and change is revealed through metaphors and symbols. The river is the most important metaphor as it represents the ebb and flow of human life, and Yasodhara’s interior self is apprehended through it. For most parts of the novel, she is a bend in the river who desperately tries to hold back the currents which swiftly flow by. However, in the last section, in keeping with the story, she abandons her attempts and learns to “truly be a seedpot, carried along by a river current.” Since this is Yasodhara’s phase of awakening, the tenor of the novel changes. The interior form is diminished in favour of a remote style suitable for recording external events and for recounting sermons that the wandering bhikkhunis preach to each other while on their way to Vesali. The novel foregrounds Yasodhara’s role in convincing the Buddha to let women join the sangha. The Buddha finally agrees and the novel ends with Yasodhara’s realisation that she’s “becoming less seedpot and more river.” Yasodhara wins, but not as the girl, wife, or mother who resisted the changing tides.

Selvadurai’s innovations are interesting, but is his realist style consistent and is he successful in integrating Yasodhara’s changing tale of desire and release within the demands of the legend? Readers will have to decide.