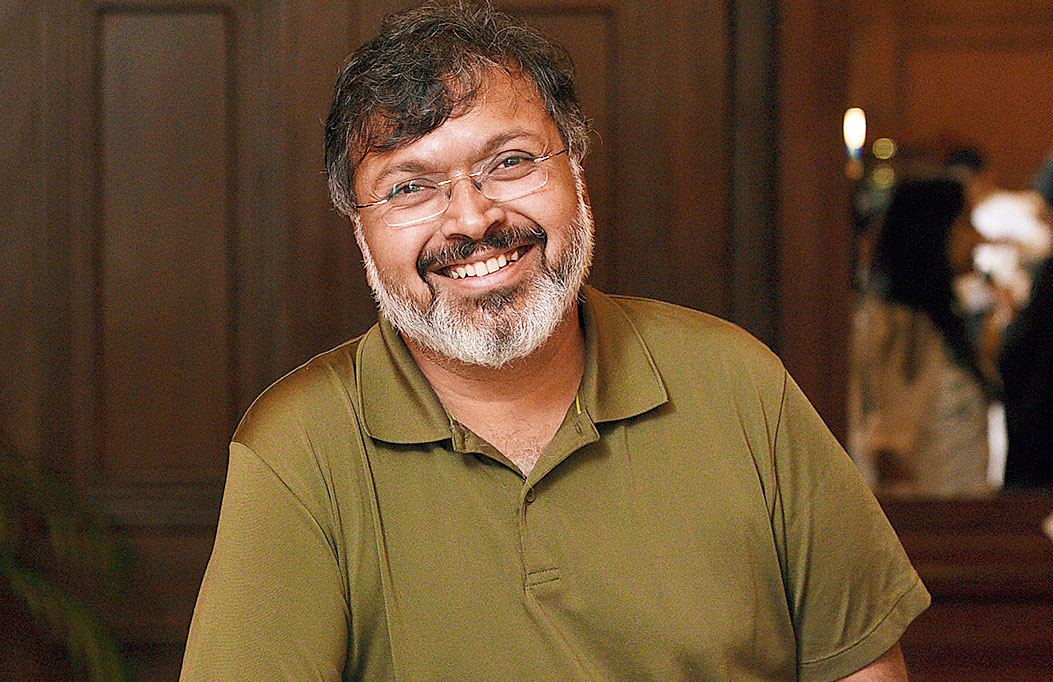

Mythologist, author, illustrator, orator and trained medical professional — Devdutt Pattanaik wears many hats, all of which came to the fore as we chatted with him on the sidelines of his talk on ‘Teacher as the Guru’, presented by Millennium Mams’, at Taj Bengal recently. Excerpts from the t2 chat...

What took you so long to talk about Krishna, given that you have already extensively discussed the Mahabharata and the Ramayana? Is this an accidental arrangement or a deliberate arrangement, according to your favourites?

You see, Ramayana ke baad Mahabharat was a no-brainer. Krishna is a complicated story. I didn’t feel that I was ready for it. I was not able to catch the spirit of the book. I had the stories, I had the data, but that’s not enough to turn it into a book. A book is much more than a collection of facts, you need something more. And I was not able to get it, and it was becoming very forced. I said I’d wait until I’d cracked it.

What is that feeling?

Read it, no! (Laughs) It’s basically trying to connect the romantic Krishna with the statesman Krishna. Historians will say that they’re two different characters, because we can’t believe that a person can be two things at once, you know. Why can’t a person be both romantic and a statesman at the same time but in different spaces?

How is this book different from My Gita?

My Gita is basically a discourse on Vedic thought. It is contextualised by the Mahabharata, but the ideas are far greater than it, although the context does play a very important role. There is no romance in the Gita, and with the exception of one or two abstract verses, there is no rasleela, there is no bhakti in the larger sense. It’s a very simple, earthy, fragmented thought on bhakti. It’s bhakti more in terms of submission to a larger thing. It’s not affectionate, it’s not about madhurya bhava. That comes much later, and also folk poetry, from where the character of Krishna comes to us. None of this is there in the Gita. It’s a very Vedic text with Vedic language.

Was your characterisation of Krishna affected at all by the later texts, such as Gita Govinda, the poems of Vidyapati, the songs of Meera Bai?

It was. It’s very interesting — the later part of Krishna’s life was written by very Brahmanical, elite sources, and the early part of his life was written by more folk poets. There is something more grounded and earthy about it. And the early part was written later — historically, it comes much later, around the 13th to 15th century AD. And after some time, people just forget the younger Krishna. Historically and socially, lots of things changed.

The later sources show Krishna in a very rural setting, living a carefree life. It’s like most people in India, you know... you grow up in a small town, you live in a very simple world and then you move to the big city, and you deal with the big people. Does it affect you? Do your rural roots affect you? It’s like a journey from Bharat to India.

Would you agree that Indian mythology functions in such a way that it presents multiple positive perspectives on and facets of masculinity, and gender in general, via its characters?

In a way, yes. See, all mythological characters around the world are essentially solidified, coagulated concepts. So from concepts, you get characters. It’s a simple way of explaining things and it also reveals how much depth there is in a culture, by the number of characters and how much of concepts you are discussing. You do find that there is not much exploration of gender and masculinity in the Biblical traditions — or of femininity. Here, you have Radha to deal with, Yashoda, Devaki, Draupadi, Kunti, Gandhari, Satyabhama. You don’t get this richness everywhere.

What, in Indian mythology, do you think encouraged storytellers to look at these different aspects?

See, the men in these stories do not represent men and the women don’t represent women. That’s the biggest mistake people make. You can’t say Lakshmi is embodying wealth or a woman. She embodies the idea of wealth in the form of a woman. This is the problem with metaphors around the world. India is too rich in metaphors to be taken literally. It’s the end of Indian wisdom if you do. And metaphor is an indicator of how refined your thought is.

You are part of a resurgence of writers taking inspiration from Indian mythology. Unlike most other authors, however, you write non-fiction. Why?

They are fiction writers for whom mythology is the field in which they function. I am not a fiction writer. I am a commentator, a bhashya, a nibandha. Fiction, I’ve written only one — The Pregnant King. My retelling is also a way of explaining. I would have been called an akhyankar in ancient times — someone who tells stories and helps people to understand the stories, not just narrate them like a performer. It’s an ancient tradition, just told in English with text and style and in a very urban way. That’s why Indians are connecting with it rapidly. It’s something that Indians have always been familiar with. It’s never done in an English-speaking space.

You have written 47 books! How do you find the energy to keep writing, especially given that you also illustrate your own books?

I love this. So every time I write a book, I’m happy. It’s an addiction. People do different things to be happy, I write to be happy. Forty-seven is an indicator of happiness, I guess! (Laughs)

I do know that if you put all my books together in one pile, including translations, then that pile is taller than me! (Laughs out loud) I’ve been looking for a photo shoot like that.

Are there people within India whose work with mythology you love, academically?

Not many in the mythology space. There is no mythology department. I really like Purushottam Agrawal. He’s a Hindi scholar and we’ve done a book together. He validated my gaze in many ways, because he writes in Hindi and he draws from Kabir and other ‘Early Modern’ sources, as he calls them, and his lectures are very similar to mine — social contextualisation, critical appreciation, not taking extreme sides, recognising the complexities of gaze. I’m sure there are many scholars, but you see, we don’t publish our scholars as much as we should. The books of the West are much more accessible. I feel bad about this. There is also Nandita Chaudhury of Lady Irwing College, Delhi, who told me, “Devdutt, they are using Western textbooks to study Indian texts and those textbooks cannot be applied here.” We are not a documenting people, we are an oral people, even today.

Would you ever consider going into other forms?

I wouldn’t. I would support people — I’m working with Amruta Patil on a graphic novel, but I wouldn’t go into it. I illustrate in a very simple way. You should know what you’re good at and stick to that. I’m happy where I am.

Which came first, the writing or the illustrations?

Simultaneously. I’m trained in medicine. In science, you know, whenever you’re giving an answer, to get high marks you’d illustrate. I realised very early on, as a child, that I enjoyed picture books because they would talk to me both visually and cognitively. I cannot write without drawing. I really love the visual medium.

How intimately connected are your illustrations to your writing?

Very closely and very clearly. For example, if you look in Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling Of The Mahabharata, the chariots look nothing like the Amar Chitra Katha chariots we see, which no horse would be able to pull! They would be crude carts.

Then, how should a rishi look? What should a woman wear? I just want visuals to break from the Bollywood idea of costumes. Also, in an image of Krishna, traditionally Krishna’s right foot has to always point towards Radha. The left foot has to move away from Radha. I’m very consistent about this. Then, Krishna’s earrings, you’ll see that it’s fish-shaped. It’s makra kundala or matsya kundala — Capricorn. In Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of Ramayana, I wanted to show Rama going through the changes in his life. So at first he is clean-shaven, in exile he has a beard, as a king he has a moustache. So you see a shift. These things are not random. There are a lot of details, if one pays attention.

Have you been inspired by any writer in your storytelling?

I read mostly non-fiction. I like Myth (The New Critical Edition) by Laurence Coupe from the Manchester Metropolitan University. It influenced me greatly. That’s when the penny dropped. I keep emailing him and telling him, “Thank you so much for your work”, and he tells me, “When I read your work I can’t see what you’ve done with mine, it’s like another planet! I don’t even think I have influenced you.” He helped me formulate words, you know, words that I didn’t know how to express. And that I think is invaluable. I like Yuval Harare. There are many inadequacies in his book. He’s become very famous and I want to tell him (grimaces), “Can’t you see it?!” But his clarity of language and thought is fabulous.

Which non-mythology books are on your TBR list right now?

Right now, I’m editing a book which I’m very proud of and excited about, so not really reading at the moment. It’s called Ramayana v/s Mahabharata. Since everyone likes combat nowadays, I wonder who will shout down whom.

3 of Devdutt’s widely read titles

Shyam: An Illustrated Retelling of the Bhagavata Book cover

Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of Ramayana Book cover

My Gita Book cover