For mere mortals like us, it was always great fun visiting a record store. Music under one roof. You could feel, if not hear, the emotions sheathed delicately within the artwork of each album cover. Love, devotion, surrender. Every visit is a new experience. Just like the change of seasons. Always a new surprise. But, how would it be, you might ask, for the star performers themselves?

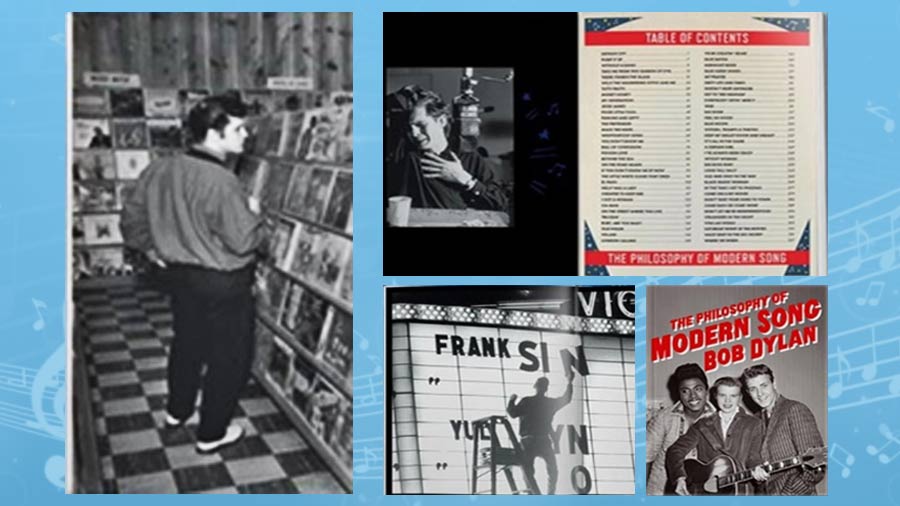

There's Elvis Presley staring at a rack of records. The black and white freeze-frame, upfront in Bob Dylan's new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, has the King looking at a tempting display of records. He seems to have stopped in his tracks, his face at a gentle tilt. Follow his gaze and it's a howling Little Richard he's looking at. Or is he? Nearby are a couple of Harry Belafonte discs. Maybe, he got to humming Jamaica Farewell. Or maybe not. For, a row below, out of his line of vision, is an Elvis record, his own album of songs. He noticed, right? What was he thinking? We'll never know.

It's what a song makes you feel about your own life that's important, writes Dylan early on in this effusive exposition of the Great American Songbook in the form of a 66-song diary that is at once affectionate, incisive and meticulous in the myriad ways he dives into the heart and soul of each number, most of them spanning the ’50s and ’60s. In the process, he is revealing a bit of himself too. Among the artistes and music groups whose songs make the Dylan cut, some lovingly hallowed by their own myths, are Little Richard, Elvis Costello, Perry Como, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Pete Townsend (WHO), Jackson Browne, Bing Cosby, The Temptations, Ray Charles, Carl Perkins, Jimmy Reed, Nina Simone, The Allman Brothers, The Eagles, Johnny Cash, Judy Garland, Nina Simone, the Grateful Dead and of course Elvis. Dylan is doffing his hat to the genius each one of them exudes, the earliest pick dating to 1924, the most recent 2003. He is helping us do that again, having done so earlier with Theme Time Radio Hour, a series of 101 broadcasts of musings and music.

The research for that radio programme helped him begin work on this book back in 2010. Here, the stories behind the songs are generously embellished with photographs, magazine covers and movie stills. It is quite a romp this coffee table labour of love, smaller in size than the regular outsized ones of the genre but surprisingly heavy. The headlines for each chapter are in bold, the font a bit loud and italicised for heft, giving the whole spread a carnivalesque feel. Not surprising since all that the little Zimmerman ever wanted to do was run away with the visiting circus party back in the day in Hibbing, Minnesota.

Brevity is the soul of wit. So said the Bard who came before him. And our present day laureate adopts that maxim as he proceeds to unspool the songs he loves one by one, layer by layer. And while doing so, he is dishing out little gems _ of insights laden with profundities like only he can: “Music, like all art, including the art of romance, tells us time and again that one plus one, in the best circumstances, equals three.” Or factoids that are plain hilarious: “The Fugs get their name from a Norman Mailer novel called ‘The Naked and the Dead’. When ‘The Naked and the Dead’ came out in 1948, censorship rules at the time forced Mailer to substitute the word fug for f***.” The Fugs chose the name they did, opting for the “safer route so the records could be purchased in a record store and not in a back alley.”

Dylan’s book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, on a Times Square display. Instagram: @bobdylan

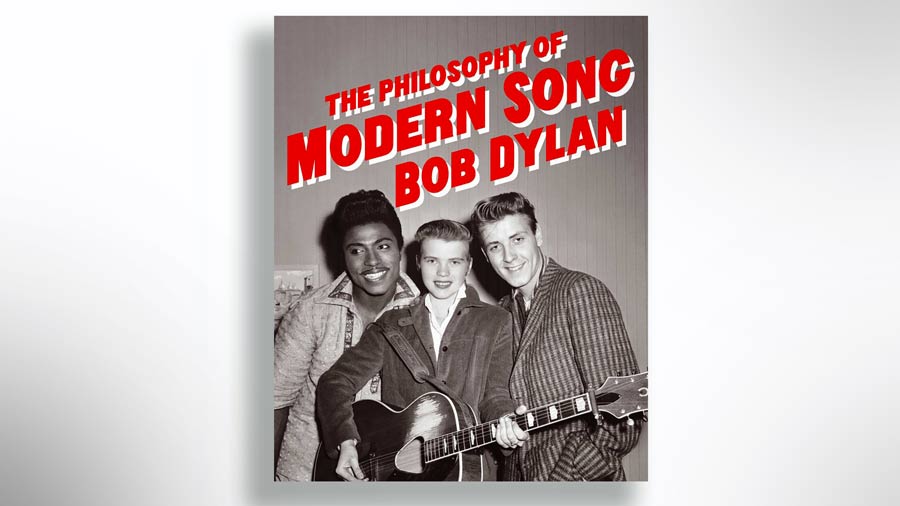

While peeling off Tutti Frutti, Dylan reveals how Little Richard, always the master of the double entendre, was really singing about this gay fellow and the two gals Sue and Daisy who are both transvestites. Who would have known? Only Pat Boone, he believes. The rest sang it without ever figuring out the triumvirate’s backstories. Little Richard, therefore, was a preacher and his song, Tutti Frutti (1955), was sounding the alarm, notes Dylan in an appraisal that is deeply personal. For Little Richard was his guiding light when he was a boy, Dylan had revealed in an elegy at the time of his passing; the “original spirit” that moved Dylan to do everything he would do. Here, Little Richard is on the cover, alongside Eddy Cochran and Alis Lesley who, back in the day, was referred to as the “female Presley”.

Detroit City (Bobby Bare, 1963) is a song we can all identify with. Having moved to a big city to make a life, you realise soon enough that life hasn’t turned out as you hoped. You yearn for home knowing it’s the one place you will be welcomed back for what you are and not what you failed to be. Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me (Billy Joe Shaver, 1973) is the riddle that offers the much-needed counterpoint. Keep moving. It’s better to let the train keep rolling on. Well of course. That’s why musicians tour. Dylan’s is called The Never Ending Tour. “You give pleasure to the people and you keep your grief to yourself.”

Two Elvis songs find mention. Money Honey (1956) offers an opportunity for Dylan to dwell on, well, money vis-à-vis art. He is having fun. “Art is a disagreement. Money is an agreement. …. The only reason money is worth anything is because we agree it is,” he says, citing Venezuela which declared in 2017 that it doesn’t have enough money to pay for its money. “But you know what, Venezuela’s still here. Because, ultimately, money doesn’t matter. Nor do the things it can buy. Because no matter how many chairs you have, you only have one ass.”

The other Elvis track Dylan lets the needle fall on is Viva Las Vegas (1964), the ode to the gambler in the city that turns midnight into morning. It was here at the Hilton that Elvis played and sang night after night even as his health and performance deteriorated. The book is dedicated to the song’s co-writer Doc Pomus, who gave up the music world’s uncertain ways, but was dragged back in by the likes of B.B. King and Dr John. None of them is around. “Elvis, BB and Dr John are all gone,” Dylan deadpans. “Meanwhile, Hilton now owns thirty-one hotels in Las Vegas. The house always wins. Viva Las Vegas.”

Revelations, warnings, stories, music industry gossip and nuggets of history, Dylan’s Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster), his first book of new writing since 2004’s Chronicles: Volume One and since winning the Literature Nobel in 2016, is replete with all and more. It also draws a few conclusions. With Dylan, the self-professed song and dance man, these are sweeping. Naturally. Hence, Grateful Dead is essentially a dance band playing for an audience that is also part of the band. Let’s not forget (can we ever?) Dylan has toured with the Dead. So you better believe him when he explains why Dead is unsurpassable, citing the presence of the jazz classical bassist, Phil Lesh, and the Elvin Jones-influenced Bill Kreutzmann. Lesh is described as one of the most skilled bassists in subtlety and invention, who combined with Kreutzmann, helms a rhythm section that is hard to beat. Then there’s Bob Weir, whom he calls an unorthodox rhythm player banking on strange, augmented chords that somehow match Jerry Garcia’s guitar. With elements of traditional rock and roll and American folk music, the Dead, with three main singers, two drummers and triple harmonies, is difficult to compete with. “A post-modern jazz musical rock and roll dynamo.”

The Philosophy of Modern Song is also an audio book starring the likes of Jeff Bridges, Helen Mirren, Sissy Spacek and others who join Bob Dylan in the reading. Instagram: @bobdylan

On Bobby Darin, whose Mack The Knife (1959) is described as a murderous ballad from The Three Penny Opera, Dylan is sympathetic. Darin was in the Frank Sinatra mould but not quite. The world could only stand one Frank, he says. “Nobody could follow that road. Not Tony, not Dean, and certainly not Bobby Darin.” About Strangers in the Night (1966), Dylan reveals Sinatra hated it. Even though that was the song which toppled the Billboard Hot 100 charts in 1966, unseating some of the iconic representatives of the British invasion, like Paperback Writer (The Beatles) and Paint it Black (Rolling Stones). There is a twist in the tale when it comes to the writer of the song, which had gone through at least two sets of lyrics with many staking claim to its authorship. Dylan presents the entire story, without vouching for its veracity. In short, it’s about this Armenian pianist and composer, a Beiruti immigrant who was living in New York at the time, courtesy Iran’s Shah Rehza Pahlavi. Other claimants include a Croatian singer and a French composer. Tying up these various strands is the Avo Xo, a Dominican cigar, over two million of which are sold every year now. Go figure.

So, what makes a good song? Dylan offers clues. A big part is editing, distilling down to essentials. Look for the artistry in what is unsaid. Don’t fall for the trap of easy rhymes, like revolution/evolution/air pollution, he adds, but clarifies that only in the hands of a John Lennon can a “post-modern campfire song [Give Peace A Chance]” come to life with dogma descriptions such as ‘bag-ism, shag-ism’. Yet, if there was anyone who could pull off so-called moon/June songs with aplomb, it would be Frank Sinatra. He could break people’s hearts with his renditions even though putting melody to personal diary entries doesn’t quite guarantee a hit song. Dylan would know, having reprised a bunch of Sinatra classics in his own album Shadows in the Night (2015).

Dylan is also taking a swipe at those who often try to read lyrics deadpan to squirm at their apparent lack of profundity, highlighting how melody is crucial for the words to open up and bestow in them meaning and purpose. Like in, say, Peter Green’s Black Magic Woman (1970), first featured in the Santana album Abraxas, the words don’t exactly leap out of the page _ “In two of the three six-line verses, one of the lines is repeated four times.” Yet, in the hands of Carlos Santana’s guitar played to Latin polyrhythms, the song instantly becomes what it is meant to be: the irresistible seduction of this out-of-body femme-fatale or unseemly creature with dark powers.

Part of the joy of reading Philosophy of Modern Song is Dylan’s writing. Alternating between smooth and jagged, it reminds us of the musical meter of his 2020 studio album Rough and Rowdy Ways. Most sentences are short and pithy. But when they are long, they’re playful, alive, heart-melting. “He dips down to a low baritone and then goes up into that high tenor… he hits a high note as pure and as clean as a mountain stream,” he says about Johnny Paycheck’s rendition of Old Violin (1986). At times though Dylan ends up repeating himself, but it matters little since it is another song, another story and another time he’s describing. The book is one long, very long, song. The chapters are the verses. They are of uneven length, meant to be read in varying tempo, holding forth on music pertaining to a time that has long gone. Yet it is music, and therefore, timeless.

What does the Philosophy of Modern Song mean to someone growing up outside of America, say in the sub-continent that wears, albeit lightly, its own mashup of musical history? The palette of songs that Dylan uses to paint this mural in tribute is not all made of familiar colour and sound _ there are several in his selection that I didn’t know of. Thankfully though, all the songs he covers are floating about in the streaming universe waiting to be clicked on. And played. As I did. We can all listen to them if we choose to and relive some of the stories and events as they are said to have happened. Dylan is opening new doors, leading us up the garden path to a nursery of rhyme, song and slices of history. It is for us to tune in. Maybe even sing out loud.

‘The thing about being on the road is that you’re not bogged down by anything’. Artwork (not in book) by Bob Dylan. Instagram: @bobdylan