The Khoshbag cemetery is located on the west bank of the Bhagirathi river, about a mile upstream from Murshidabad, the erstwhile capital of undivided Bengal. A perpetual pall of gloom hangs over the place whose name means garden of happiness and where sleep two nawabs of Bengal and their relations.

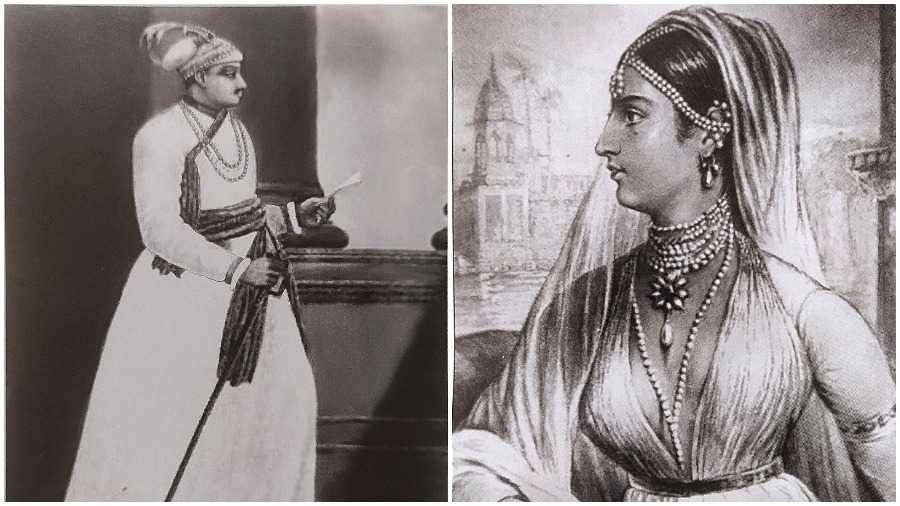

The modest mausoleum at the centre of the compound shelters the grave of Alivardi Khan, who was nawab from 1740 to 1756. Close to him lies buried his grandson Siraj ud-Daula, the nawab who ruled for 15 months (1756-1757). Siraj is remembered as the last independent ruler of the subah of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha and India’s first freedom fighter. He was the one Robert Clive routed at Plassey and opened Hindustan up for occupation by the British.

The grave adjacent to Siraj’s belongs to his wife Lutf-un-nisa or Lutfa. The grave beside hers is Heera’s, also known as Aleya Begum — another wife of Siraj’s. Not much is known of Heera except that she was the sister of Mohanlal, Siraj’s trusted friend and official.

In the Battle of Plassey, Mohanlal fought valiantly. An ace cavalryman, believed to be of Kashmiri origin, he was grievously injured on the battlefield. Says Amit De, professor of history at Calcutta University, “There are no records about what happened to him and Aleya after that.”

This hiatus in history intrigued Amit’s father, the late Amalendu De, a historian and former head of The Asiatic Society, Calcutta. Says Amit, “Until his death in 2014, my father continued his research.”

De Sr frequently travelled to Murshidabad, and different parts of Bangladesh. De Sr’s daughter, Tapti De, also a historian, remembers him interviewing members of the Lala Dey family.

De Sr’s book Sirajer Putra O Bangshadharder Sandhaney (In Search of Siraj’s Son and Descendants) was published in 2012. According to it, the Lala Dey family actually descended from Siraj and Aleya’s son. De Sr wrote in the fore-word to his book, “My research revealed that Aleya gave birth to Siraj’s only son. Their marriage was solemnised following Islamic rituals by Nawab Alivardi.”

Shyamal Dey, who is a fifth-generation descendant of Siraj, has researched and codified the family lineage in the document Heera’s Legacy Sourced by The Telegraph

After Siraj’s defeat in the Battle of Plassey on June 23, 1757, Mohanlal, rode away with the boy to Mymensingh, now in Bangladesh. Later, he convinced a zamindar to adopt the boy and escaped to north Bengal in disguise. De Sr writes that Siraj’s only male descendant was renamed Jugal Kishore Ray Chaudhury.

Lala Ajay Kumar Dey, who lives in Delhi and is the CEO of Global Concierge India, says, “Our family lineage was a closely guarded secret. We knew we were somehow related to Mohanlal. Prof. De helped us join the dots.”

Ajay, a sixth-generation descendant of Siraj, came to know of the family secret from his grandfather Lala Bijoy Kumar Dey. “This happened in Shillong when I was nine.” He says, “The British, along with Mir Jafar, had laid a trap to catch Mohanlal; they kept Aleya in a safe house and expected Mohanlal to come to rescue her. But when Mohanlal did not come, she was tortured and hanged to death.”

Bijoy Kumar, an advocate, moved from Sylhet to Shillong in 1927. One of Ajay’s cousins is writer Bijoya Sawian, who grew up in Shillong in her maternal grandmother’s home in a “secular, all-embracing atmosphere where indigenous Khasi culture is firmly entrenched”.

Says Bijoya, “When I was growing up, my father talked about Sylhet with great affection. Mohanlal was often mentioned as a great nobleman and soldier, friend and confidante of Siraj and an ancestor.”

Lala Shyamal Dey, who works in Abu Dhabi, is a fifth-generation descendant of Siraj. He has himself researched the family lineage; his “Heera’s Legacy” is a comprehensive document. According to it, Jugal Kishore was adopted in 1758 by Mymensingh’s zamindar Krishna Gopal Ray Chaudhury, following Hindu rituals. Some years later the zamindar died. His widows wanted to deprive Jugal Kishore of his rights. They started threatening him, saying they would reveal his birth history to British officials and Mir Jafar’s spies. That is when Jugal Kishore left Mymensingh and went to Sylhet.

Years later, shortly before his death in 1811, Jugal Kishore revealed his secret to his son Pran Krishna and asked him to bury his body instead of cremating it. Later, Pran Krishna’s son Sourindra Kishore changed his name to Lala Prasanna Kumar Dey to escape the prying eyes of the British.

Atiar Dey, a barrister based in London, is a seventh-generation descendant of Siraj. He says, “I think at some point in life each of us would like to know who we are and where we come from.”

After the publication of De Sr’s book, Lala Shyamal Dey, along with his siblings and other members of the extended family, travelled to Murshidabad to pay their respects to their ancestors. He says, “As part of a general exercise outside India, a family member’s DNA was tested and it was found to have affinity with those who have origins in the Arabian Peninsula; if tested, all family members should have remnants of the DNA.” Siraj ud-Daula’s paternal grandfather was a mercenary of Arab origin in the Mughal court, he explained.

Bijoya recently finished writing a book about her ancestry. In the book, which is yet to be published, she writes about the Siraj connection. The family feels relieved that after so many years they might now be able to claim their illustrious heritage and help rewrite India’s colonial past.