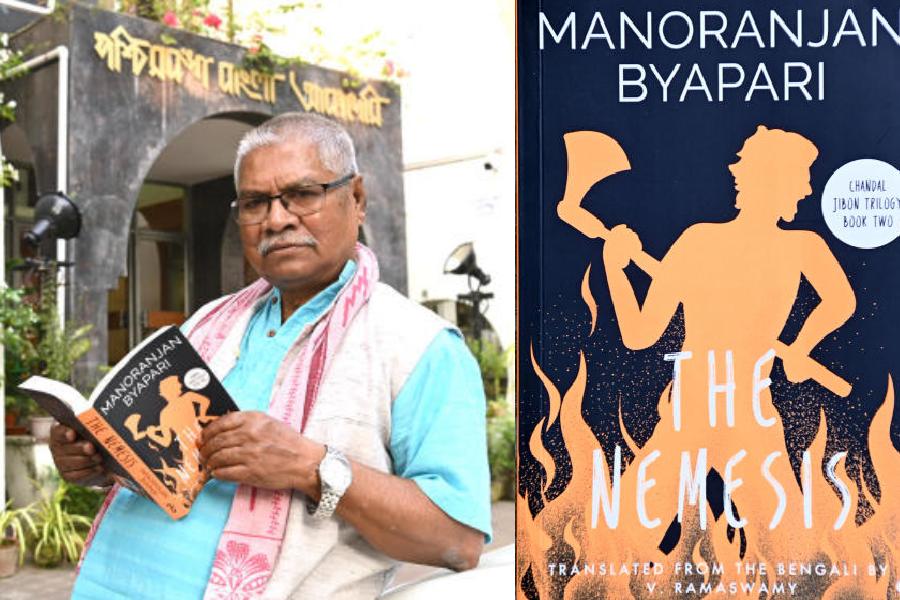

Ditching the red tapism of MLA Hostel on Kyd Street, our initial venue for the interaction, we headed straight to Paschimbanga Bangla Academy at Rabindra Sadan, where Manoranjan Byapari felt more at ease. The author and MLA, who is the chairperson of West Bengal Dalit Sahitya Academy, has been championing the cause of Dalits with his writings — essays and books, in simple and honest words.

Byapari, whose life’s trajectory is no less inspiring, writes in Bengali and each of his books gives the reader an insight into the life, hardships and everyday struggle of the marginalised section. His books also reflect the anguish of a deprived community which was palpable when we sat down to talk about his novel, The Nemesis, in one of the rooms of the academy. Part of his Chandal trilogy and an extension of his memoir Itibritte Chandal Jibon, translated into English as Interrogating my Chandal life: An Autobiography of a Dalit, which won The Hindu Prize, The Nemesis is on the JCB Prize for Literature’s shortlist. The winner will be announced on November 18. Dressed in his trademark short kurta and pants with gamcha, Byapari had a candid conversation with The Telegraph.

You are not new to JCB Prize for Literature. The Nemesis is your third book that has been on the list in the last three years. Since translation has opened literary boundaries for you and have put you in the mainstream, has it changed your writing or thought process?

These books were written much before I came into contact with JCB. I don’t write while being influenced by any prize. When Westland read my books and an agreement happened, literary awards followed. Perhaps that influence or acknowledgement that I am writing for a bigger audience will happen now when I write about my Bidhayak jibon. Winning is not important for me but everyone on the list expects to win.

The Nemesis is the second book in the Chandal Jibon trilogy. Are you already through with the last instalment?

Yes, the book has been translated and it has already been submitted.

Chandal Jibon is your first multi-series book. How is it different from writing standalone books?

The story is essentially about a person’s life but life changes every week, every month and every year. One incident is succeeded by another; one struggle is followed by another struggle and every time a new ecosystem is created, a new life is born. So all this couldn’t be contained in a single book. Hence, I had to resort to a trilogy to tell the story in detail.

When did you decide that it will be a triology?

I used to write annually for a publication and three stories came out in it and then I stopped. It ended with the character going to jail. However, the publishers could make out that the stories were not fiction but my life’s stories, so they urged me to write a memoir. I wrote Itibritte Chandal Jibon which was around 1,000-1,200 pages and it records my life till 2021. This is definitely a continuation of my memoir as it goes beyond 2021 and talks about this different life that I have lived. To write so much and considering the attention span of readers, it had to be divided into multiple books. However, Itibritte Chandal Jibon is different from Chandal Jobon trilogy. There’s more creative freedom in a novel than a biography that follows a set chronology. The novel brings into picture a lot of people who are connected to me and who came in contact with me.

Out of the three books in the trilogy which one was more challenging?

I would say all three were challenging because it’s not about three different incidents or people but one person’s story. A lot of people have written about us but they don’t really know our situation and our lives. A lot of people show jail scenes in cinema but the reality is far from what’s shown on the screen. The life that I have experienced is very different.

Your first-hand experience is what makes your writings on Dalit literature strong. How do you think you have evolved as a writer?

The subject that I deeply know and have experienced, I write about that. I don’t depend on imagination. Whatever I have seen and I am seeing, I write about that with utmost honesty. This is not my profession; there were things inside me that needed an outlet and I held the pen. I am not highly literate to be able to understand the nuances of writing but the truth is so strong that it fails fiction. People have asked me if what I have written is true, as it’s hard to believe. Once I was about to be thrown into a river, and I could write about that rush of emotions that I will be killed in a few minutes, only because I had experienced it. It’s not possible to imagine this and then write. Perhaps fiction writers can pull it off but it will not sound complete.

What was your aim when you picked up the pen?

My aim was to put forth the story of this group of people who are struggling everyday for a single meal, they are struggling to buy a piece of bread for 17 paise, which is the same price as a block of brick. And then there is the other group that is obnoxiously wealthy and wants more. Why is it that despite working hard I cannot live with decency and respect? Why is it that I cannot get medical facility being in the same country as the rich? Why I don’t have the money while others do? This is my angst and against that system.

You are the chairperson of West Bengal Dalit Sahitya Academy. How are you promoting Dalit writers and literature?

Our writings are not published and not trusted as well. So, we as a government body, publish writings of Dalit writers to promote them and bring to the public writings that otherwise cannot see the light of day. We do a four-day Dalit Sahitya Utsav and go around different districts and also give the winners a nominal prize. We will now explore Jharkhand for the same purpose. Dalit Sahitya is not Manoranjan’s sahitya but a movement and an initiative to create awareness among all.

Pictures: Rashbehari Das