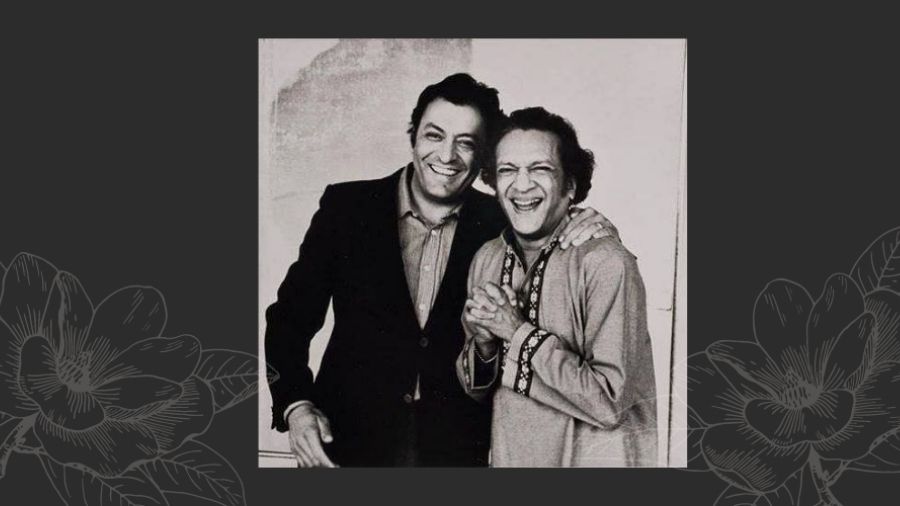

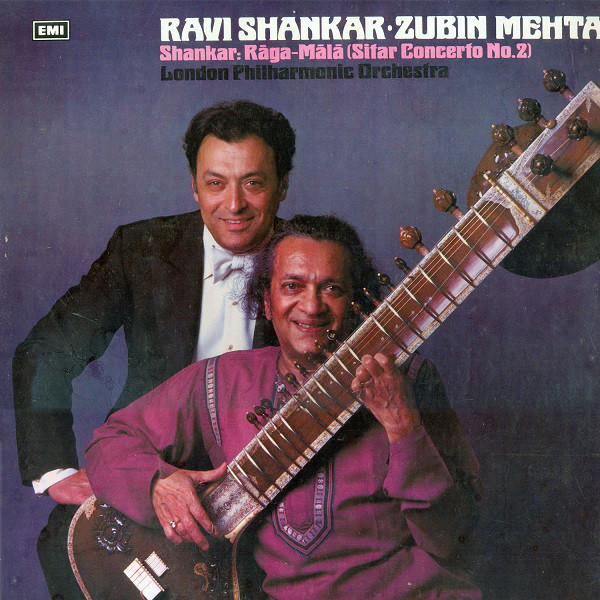

This year marks 40 years of a cultural milestone, the coming together of two Indian maestros subscribing to two very different schools of music. Zubin Mehta’s collaboration with Ravi Shankar for Raga Mala, the sitar exponent’s concerto, premiered in 1981. It was a celebration, classical and otherwise. That was also the year the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra made Mehta its Music Director for Life. Later in 2019, they performed a hauntingly beautiful rendition of Mahler’s second symphony to commemorate his 50-year association with the Israeli Philharmonic.

Mehta, who turns 85 in April this year, spoke to me from a hotel in Munich discussing Mala and Mahler, Satyajit Ray and Bombay, and why he misses talking in Gujarati. Excerpts:

Jaimin: Good afternoon Maestro, I’m a huge admirer, making sure to watch your performances instead of only listening to them for the elegance of your baton.

Zubin Mehta: Thank you.

I tell people I was born in the city of Zubin Mehta and raised in the city of Satyajit Ray.

Well (Laughs). I’m sorry that I never met Mr Ray. When I came to Calcutta with the New York Philharmonic in 1984. We played in a big stadium.

Was it the Netaji Indoor Stadium?

Yes. And because it’s a stadium with a lot of people, I didn’t play very long serious pieces -- because in stadiums, the concentration of the public is not that much. So I did short pieces and he was very critical of me. And I’m sorry, I wanted to meet him and explain to him. But unfortunately, it didn’t happen. I’m a great admirer of him.

Do you have a favourite Ray film?

Oh, his first one -- I loved especially.

Pather Panchali?

Yes, and ‘The Room’ another one was called.

The Music Room… Jalsaghar?

Zubin Mehta: Yes. Beautiful. Let’s start.

Many conductors have tried to explain their role and contribution to a performance. I want your take. What does an orchestra conductor do with a baton, standing on a podium, playing no musical instrument? Are the musicians supposed to always keep their eyes glued to you?

Well, most musicians do have their eyes somehow glued to the conductor but of course they are reading the music too, so they can’t be completely glued but the rhythm, the beat of the conductor is very important for the musicians. Of course the conductor’s work during the rehearsal is extremely important because he analyses the piece for them and he tells them the message of the composer. A Beethoven Symphony, for instance, is usually in sonata form. So they have to know where the exposition is and when the exposition goes into the development and then the development turns back into the recapitulation. One has to alert musicians to this form. Form is very important in classical music, whether it’s Beethoven or Mahler.

How are Zubin Mehta’s interpretations of Beethoven compositions different from others?

Everybody has interpretations. We all have to know the message of the composer… The message first starts with the tempo and then the phrasing and then the balancing of different parts of the orchestra. Every full stop and comma of the composer is observed. We play every note that the composer has written without skipping anything. And as I told you, the main work is all in the rehearsals.

I saw a video where a horn player is peeved when the percussionist comes in sooner than expected. And you realise the horn player thought, wrongly, that it was intentional. So you calmly speak to the percussionist and pacify him.

It was an honest mistake, nobody does these things purposely (laughs).

What makes a conductor great or really good at what he’s supposed to do?

His knowledge of what he is interpreting. You know, musical periods change around every 50 years to make it a round figure. We had Bach in the 18th century and then came his children. His sons were also great composers but they changed the style and the style became classical, which was then adopted by Haydn and Mozart. That changed again. Then the great Beethoven came and not only changed that classical period but laid the foundation stones for the romantic period. From the Baroque of Bach came the classical of his sons and Haydn and Mozart, and then came the romantic period started by Beethoven and then went to its highest point with Wagner. Then it all collapsed with the collapse of tonality. The styles change and the conductor has to be at home with all styles.

Why did you choose Mahler’s Second Symphony as your final performance with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra?

That’s because I had been performing this piece with them for the last 50 years almost and it’s a monumental piece which was apt. It was ideal to close my 50 years with them.

According to you, where does the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra stand in comparison to orchestras like Royal Concertgebouw, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra and Berlin Philharmonic?

Let’s just say it’s one of the 10 most prolific in the world.

What are your thoughts on illustrious orchestras doing contemporary pop music and collaborating with rock bands like Metallica and Scorpions?

I have no experience with that. I don’t even hear that, so I have no opinion.

You recorded the music for the 1979 Woody Allen film Manhattan. How did that happen?

He wanted the music of George Gershwin, so we sat down together and we chose the right music for the right scenes and I recorded it with the New York Philharmonic in his presence.

Which is that one orchestra that you have not conducted but would have loved to?

Well, I’ve never conducted the Cleveland Orchestra which is really great. There’s no reason. Lorin Maazel, who was a conductor there, invited me often. But since I was in Israel and New York and Los Angeles, I had no time.

How was it working with Ravi Shankar?

Wonderful. He was like an older brother to me and I learnt a lot from him. A lot. He was an old sage of music and I worked with him on his concerto which he wrote for the New York Philharmonic. His second concerto. Because he couldn’t write our western nomenclature, I had a composer take the dictation from him. It was one of the great musical experiences of my life.

Apart from Western Classical, what other genres of music do you listen to? Well, I admire the early jazz musicians very much, like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington.

How do you listen to music?

Well, one listens when one can (laughs). Today, one can listen in so many different ways. Either in the car or a tape recorder.

I remember you once briefly mentioned Freddie Mercury, another Parsi musician.

Unfortunately, I never met him. I watched a lot of his tapes and he’s a great performer. Although I’m not at home with his kind of music, he’s a very great performer.

How have you been spending your time post your retirement and during the pandemic lockdown?

Well, even now, I am in Europe because Europe is at least having some kind of streaming performances. In America, there’s nothing at all. I’ll have three concerts in Munich, which will be streamed, and then I go to Milan and do an opera which will also be streamed. In other words, we do a lot of rehearsals but we don’t repeat the concerts because there’s no public. Hopefully, people all over the world can listen.

Is your Indian origin questioned because you've dedicated your life to Western Classical Music?

I left Bombay when I was 18 and immersed myself in the study of Western music and that has been my life since then. But thank God for people like Pandit ji (Ravi Shankar), I came back a little bit towards the Indian music. I listened to a lot of other Indian musicians too, especially in my youth. The great sarod player Ali Akbar Khan. I’m a great fan of Ali Akbar Khan and Bismillah Khan the shehnai player and Hariprasad Chaurasia the flute player. These are great musicians.

When did you know that being an orchestra conductor is your calling?

From my youth, ever since I grew up helping my father with the orchestra in Bombay. My first education and inspiration was my father.

Which place makes you feel at home the most?

Well, starting with Bombay and then of course I have been in America since the early 60s. America has been very good to me and my jobs in Los Angeles and New York. And fifty years in Israel.

What are your favourite food items and restaurants in Bombay? Do you like Parsi food?

There are not too many restaurants serving Parsi food but thank God for friends who have great cuisines at home. It’s not that I only insist on having Parsi food. The restaurants in the Taj Mahal and the Oberoi Hotel in Bombay are superb and I love eating there. But when I’m in Bombay, I usually eat in the homes of friends.

You’re a global citizen in the truest sense. How many languages are you fluent in?

Seven. The five European languages and two Indian. I’m not perfect any more in Hindustani (Hindi). As for Gujarati, I used to speak with my parents almost every day but even my closest friends, when I speak to them in Gujarati, they reply in English.

You received the Kennedy Center Honors in 2006. How important are accolades for you when it comes to getting recognition for work?

I was very honoured. As I told you, I’m very honoured how America accepted me for all these years. So the Kennedy Honor I was very pleased to accept. But I have to say that I have been honoured very many times by my country, India, also. I received the Tagore (Cultural Harmony) Award a few years ago and the Padma Vibhushan. So I’m very pleased they don’t forget me.

Why do you think India is not producing young conductors, and musicians like Lang Lang and Khatia Buniatishvili?

Well, because we have such a tradition of our own music, not many people study Western music. Although, you know, I have this school in Bombay – Mehli Mehta Foundation. We have a lot of young children studying music. Hopefully, somebody will come out one day.

Thank you so much for your time, Maestro. It was a pleasure speaking with you.

You asked wonderful questions. Bye.

(Jaimin Rajani is a singer-songwriter and documentary filmmaker