Since the lockdown in Kashmir on August 5 last year (relaxed in several, agonising phases over seven months and more), Sumona Chakravarty has been putting out a series of Facebook posts with the hashtag 30daysofCurfew.

In the posts, the 33-year-old Calcuttan tries to imagine what it would be like living under curfew in her own city. She tells The Telegraph, “When the Kashmir curfew happened, I started to wonder what are we even doing. We are not protesting, we are not taking to the streets. We seem to be complicit.”

Chakravarty, who has studied art and design for social change and social justice, and has a master’s in design from Harvard, adds, “From that frustration, on the 20th day of the curfew in Kashmir, I tried to imagine how I would have felt if

I was put in such a situation. And then I decided to convert my thoughts into something expressive.” She calls it a “cultural conversation”.

Sumona Chakravarty’s imaginings Courtesy, Sumona Chakravarty’s Facebook page

As the thoughts multiplied, Chakravarty moved them from her mind to social media. As 30-day challenges were the flavour of the season, she bestowed on her posts the hashtag 30daysofCurfew.

Every post is made up of a sketch and a caption. The principal characters are Chakravarty herself and her immediate family. The side cast includes neighbours, soldiers, Ramesh the grocer, the government official, the cop issuing curfew passes.

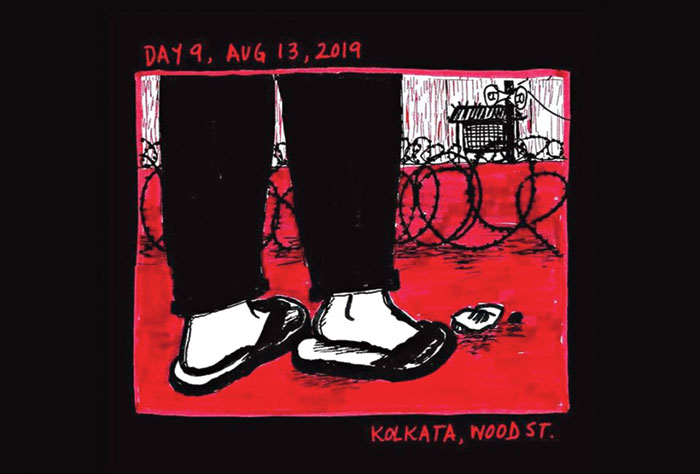

The datelines are familiar — Short Street, Wood Street. Familiar signages and landmarks loom. But what Chakravarty in effect does is de-familiarise the intimately known. One of the posts shows a desolate Park Street. She also intersperses the landscape with elements typically associated with embattled zones — checkpoints and barbed wires. The wire, in fact, curls through the cityscape, snaking its way in post after post.

Chakravarty’s sketches are simple. The only colours used are black and red. Depending on the situation, sometimes the red overpowers, sometimes the black and sometimes it is a play of white.

The post from Day 6 shows the city skyline. The caption reads: “We spent the day unfreezing leftover food, rationing for seven days... I spent a lot of time hanging over the balcony, trying to discern my parents’ home in the distant skyline. Felt like a bandh day, and despite the dull blue sky, I couldn’t shake off the feeling that we were bracing for a cyclone.”

Post from Day 9: “Overnight a new level of military infrastructure was set up — loudspeakers, bulletproof surveillance booths, cameras and rows after rows of razor barricades. As we walked up and down our street faceless men barked out warnings. We were afraid to ask what had happened.” And then the August 15 post: “A soldier stepped forward, looming over me, face hidden behind his armour. ‘Happy Independence Day. Please take a pamphlet to know about the benefits being provided to you by our Government’. I reached out grabbed it, and shut the door as fast as I could.”

A lot of the initial posts have something in the nature of a P.S. running through them. It reads: Failing to imagine what it would be to live under #30daysofCurfew in Kolkata, India. Chakravarty says, “Honestly, it is very difficult to imagine myself in such a situation. I have never experienced violence in any form. That is what privilege is and that is how protected we are.”

Although Chakravarty’s initial trigger was the Kashmir lockdown, Kashmir is only the context of this series. There is no mention of Kashmir in any post and it tends to blur in the mind of the reader, till it is replaced by empathy mingled with a sense of foreboding. In one post she writes about the New Bengal Plan, under which five lakh new government jobs are on offer. Chakravarty writes about the long line for registrations and the promise at the end of it: “Employees and their families would be exempt from the curfew, have their landlines restored, and most importantly get money in their bank within a month...”

Some might argue that Chakravarty’s position of privilege restricts her imaginings, but it does not come in the way of her empathy. Her posts lay bare not only the worst she can imagine of the city and its people, but also the worst lurking within her own self. In one of the posts she describes a situation when the domestic help, Zeena Didi, approaches her and her husband for help. She writes: “Later, I realised I could have asked her to come and stay with us, but there was a deep dividing line between us, that I failed to cross.”

Post Day 32, Chakravarty shifts gear from the imagined present to the imagined future. The post from December 29, 2020, depicts her father being interrogated about his birthplace, occupation, religion. A new hashtag joins the post, humkagaznahidikhayenge. She tells me, “In the first 30 days, I wanted to make a distant reality closer and more immediate. But after the CAA and NRC,

I wanted to show a possible future we might be facing more urgently.”

The Kashmir lockdown is over for now; to date Chakravarty has reached Day 514, but she wants to continue the momentum and keep posting once in a while. She says, “The idea was to use these 30 days as a hook, create a dialogue and get people to start talking. I shall keep posting often, just to remind people it is still happening. It is never over.”