Ms Violet Stoneham rides home from school in a hand-drawn rickshaw, after teaching Twelfth Night to a class of disinterested students. Home is in a narrow lane of decrepit houses that have seen better times, like the grey-haired Ms Stoneham.

Born in British India — to an Anglo-Indian father who worked, typically, in the railways — Stoneham’s childhood was spent frolicking, with her siblings, in spacious government bungalows. After Independence, most of her family and friends migrated to Australia, Canada, England. But Ms Stoneham decided to stay behind, hoping to integrate with the Indians and continue life as before.

Unfortunately, life was no longer the same. Younger teachers, new cultural values gradually replaced the old order. Writer-director Aparna Sen’s film, 36 Chowringhee Lane, made 40 years ago, captures the tragedy of those who did not “go back home”.

Photographed evocatively by Ashok Mehta, Sen’s directorial debut is a poignant tale of an ageing Anglo-Indian teacher whose life revolved around Shakespeare (even her cat is named Sir Toby after a spirited character from Twelfth Night), tuitions, Christmas carols and tea cakes. Played out by Jennifer Kendal to nuanced perfection, Stoneham’s story is set in Calcutta, 30 years after the British left. A new principal in the school, where she has been earnestly teaching the intricacies of iambic pentameter, demotes her to the lower classes to teach English grammar. It hurts, but Ms Stoneham takes it in her stride and continues with her humdrum, routine life, without revealing the pain within.

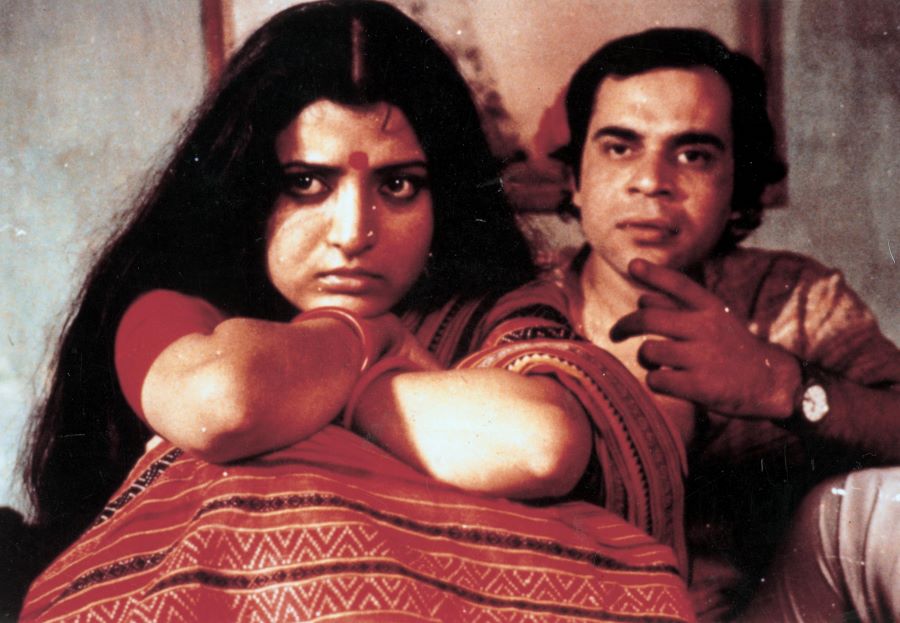

A scene from the film File picture

This routine includes visiting the grave of her fiancé who died in the World War and her brother Eddy, who lives in a home for the aged, mentally frozen in the past. “Kenny went away,”

Eddy recalls, sadly. “They all went away,” sighs his sister. “They can’t retire me so early,” Eddy continues, grumbling. “I will complain to the king.” To which Ms Stoneham reminds her brother, gently, “There is no king. The British Raj is over.” On the road outside, a protest procession is making its way, screaming slogans as it goes by.

Ms Stoneham’s niece, ditched at the altar by an Indian musician, married one of her community overnight, and migrated to Australia. “Come live with us,” she writes, repeatedly, to her aunt. But Ms Stoneham refrains from joining her as other Anglo Indians who have re-located don’t have happy stories to tell.

So, Ms Stoneham seeks joy in the altered circumstances, giving her all to her students, even letting one of them, Nandita, and her upwardly mobile boyfriend use her home to write a novel.

Alas, when she realises she means nothing to them, that they have cleverly exploited her emotions to use her flat for romantic rendezvous, her stoic back breaks down. All alone on a wide, beautiful road, constructed in British times, she shares her Christmas cake with another loner, a stray dog. The film ends with her reciting lines from Shakespeare, her ultimate solace: “Pray, do not mock me,/I am a very foolish fond old man.

Extremely moving, Ms Stoneham’s plight projects the dilemma of those who didn’t migrate after India became a free nation. A plight that never made it to the headlines, but was quietly borne by countless Ms Stonehams. What inspired Aparna Sen to write their story?

Going back to those times, Sen recounts, “It all started when I was filming as an actor in Bombay, for a regular formula film. We were waiting either for the lighting to be completed or for some actor to arrive, I forget which. Waiting in my makeup room, I started wondering if I was going to be acting in the kind of cinema I did not believe in, for the rest of my career. The very thought was so depressing that I decided to do something else, there and then. I decided to write a short story. Pondering on the subject, I suddenly remembered the old Anglo-Indian teachers in our school. Most of them were very kind and affectionate. As I wrote, to my astonishment, my story started turning into a screenplay. That is how 36 Chowringhee Lane was born.”

Sen recalls meeting one particular teacher before starting her film. “She lived all alone in her apartment. All her nephews and nieces had left India by then. When she fractured

her elbow, it was the neighbours who looked after her. I remember her being very bitter about the school and not attending her farewell function.”

Sen’s multi-award-winning film, whose art director was the veteran Bansi Chandragupta, had a predominance of soft, pastel shades. “I wanted it to resemble a rose that had been kept pressed between the pages of a book for a long time,” she explains.

A rose, which has not lost its fragrance even now. And, as migrant workers today find themselves left, high and dry, between their home and job-providing cities, Ms Stoneham’s dilemma acquires a renewed relevance. To go or not to go is a difficult question, whatever the circumstances.