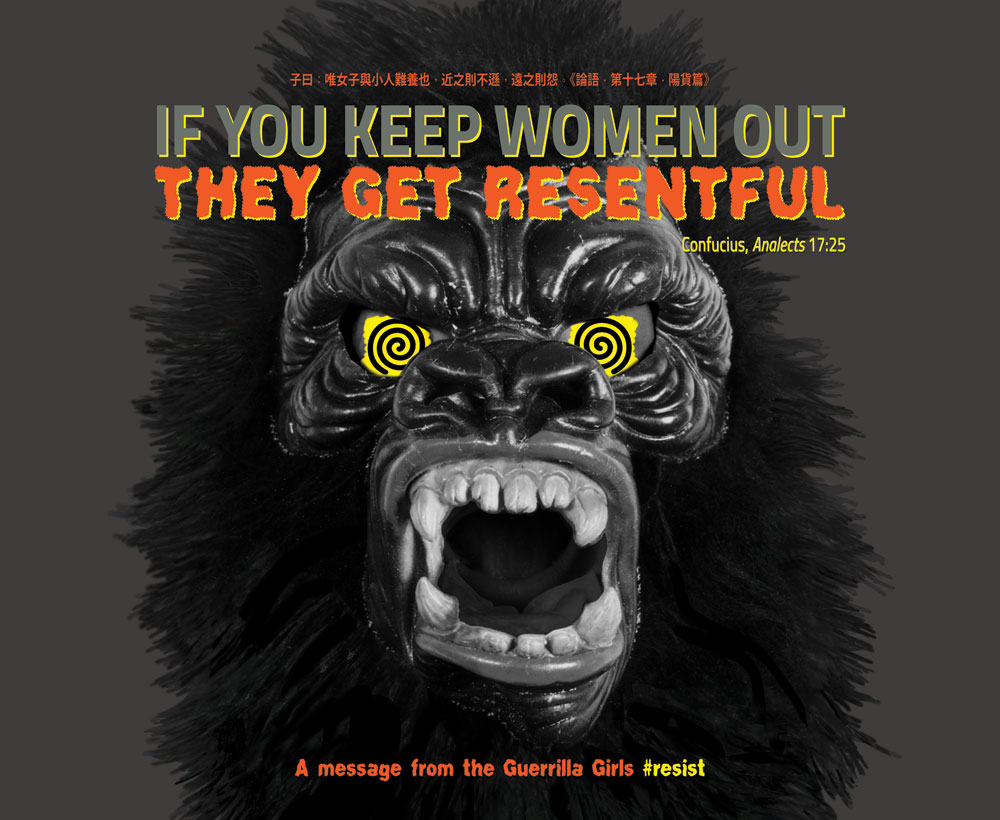

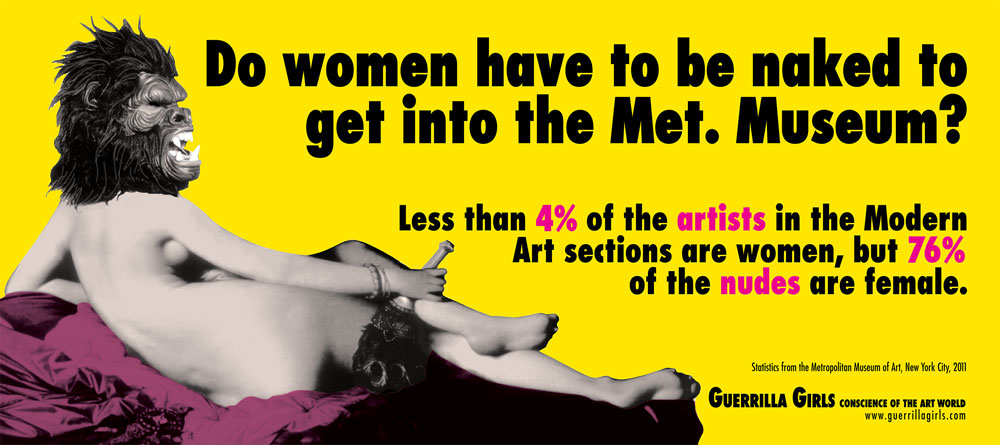

A Guerilla Girls poster from their works over the years Image: guerrillagirls.com

Much, much before Banksy graffitied his way into public consciousness, an undisclosed number of women artists, frustrated with the art establishment’s blatant ignorance of women and artists of colour, took to picketing outside the The Museum of Modern Art in New York back in 1984. They shook up the high-brow art connoisseur and forced a mainstream discourse on the hypocrisy of the art world. The year after, the Guerrilla Girls were born — an anonymous feminist art ensemble using gorilla masks, names of iconic yesteryear female artists, hard-hitting art and humour as their weapons to hold up a mirror to the art world.

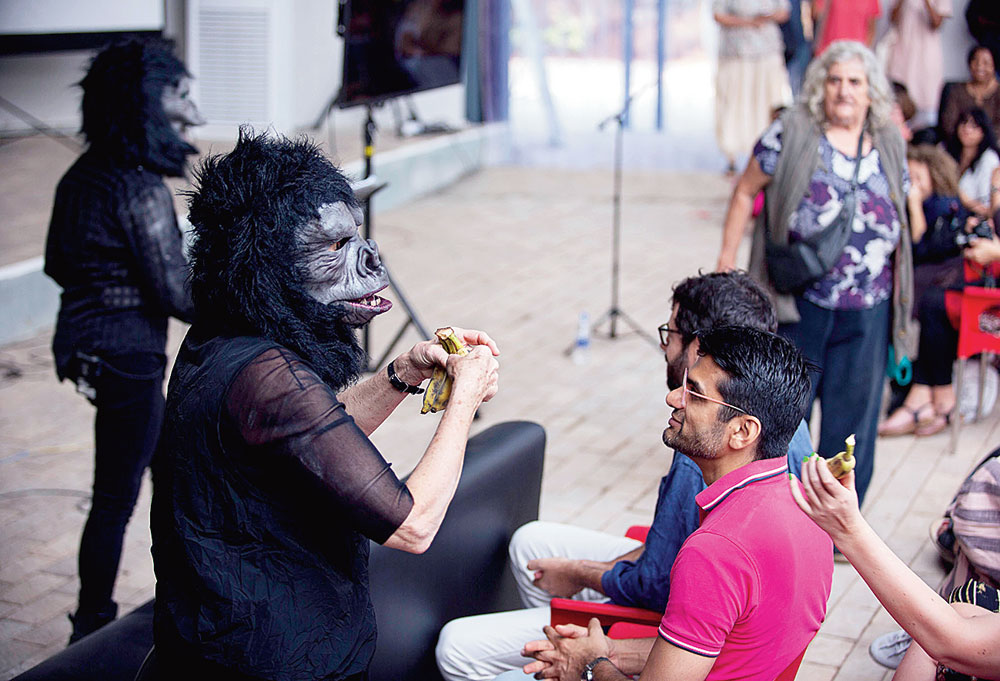

“How long was the chain formed by the women protesting outside Sabarimala? That was remarkable!” was the first thing Frida Kahlo (her Guerrilla Girl alter-ego), a founding-member of the Guerrilla Girls, asked me, when I dialled her New York number. Frida had just returned from Kochi, where she took to the stage at Cabral Yard in December with fellow founding-member Kathe Kollwitz, dressed in their gorilla masks and addressed #MeToo in India with their powerful art-jam, punctuated with a call-to-arms against patriarchy, Guerrilla Girls style. It left the Indian audience shaken and uncomfortable, poised for more discourse on the topic — “which is our agenda!” added Frida.

Excerpts from a chat with Frida:

A group of women picketing outside The Museum of Modern Art back in 1984 — take us back to the start…

Well, there’s a creation story to every social history movement and actually our tipping point was an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA in New York City) the year before we formed, and it was a show that was built up in the press as an international survey of paintings and sculptures. Of course it was totally Euro-centric and out of nearly 200 artists in the show, only 17 were women and there were even fewer artists of colour. And we asked ourselves, ‘How could this be an international survey of paintings and sculptures when it was so unbalanced, in terms of representation?’ And then the curator made a statement to the press, basically bragging about the show, saying that any artist who was not in the show should rethink “his” career and that pronoun sort of stuck in our minds. And we were like, ‘Aha? We get it!’

There was gender discrimination from the get-go and also a total lack of diversity. Guerrilla Girls didn’t exist then but a bunch of us went to MoMA and picketed the show — in a very traditional way with placards, chanting and a picket line.

At the end of the day, the only thing we accomplished was that we made a lot of people angry. We realised that the public really thought that the art world was a meritocracy and we were all kind of stunned and decided that we would try to find some new ways to educate the public. We also decided to put the museums and the art world on call and really make them defend the fact that they were only showing white European and American males. So we put up a couple of posters and started pointing fingers because everyone seemed to say it was someone else’s fault. So we started pointing fingers at our fellow artists, the galleries, art critics and then the funding resources. We sort of wanted to say that everyone who participates in this system is responsible for it and you cannot keep passing the buck.

How was this received?

We put up the posters in the dead of Friday night since Saturday was a big gallery day and we would also go out with the posters ourselves — we didn’t have the gorilla masks then. So we would just hang out near the posters and listen to what people said and everyone was aghast. People started arguing — some were in favour and some were opposed. So all of a sudden, there was this discourse that came out of the posters that was very exciting to us. So we just kept going and asking questions in different ways, both in public by putting up posters, but also by being anonymous, which I think was really important because no one knew who we were. We could be anybody — we could be the people they were talking to on the streets that day or we could be working at the museum. And we really put everyone on edge.

Why did you choose gorilla masks? Was it the wordplay?

It was a lot of different reasons but the wordplay is what really made us not think twice about it. We were trying to think of disguises because we were guerrillas (the freedom fighters) before we were gorillas (the animals). We got requests for photos and we couldn’t pass up the publicity because all this time, the press was doing our work for us. So we were sitting around, trying to discuss what appearance to have and the story goes that one of our founding members was a really bad speller and she was taking notes and we realised that she was spelling guerrillas, gorillas!

And we were, like “Oh, wow!” We just jumped on it in a minute because it was claiming another stereotype as apes had always been used to diminish people and are completely misunderstood. They are very powerful creatures, stronger than humans and the idea of piling all of that on top of a female body was just too tantalising. We did a couple of photo shoots and I remember standing in the line at a bank or something and looking at the photos and nobody knew who the Guerrilla Girls were. And at that point, someone behind me looked over my shoulder and said, “Those pictures are really weird!” And I was like, “Okay, this is it! We got it!”

If we were looking to brand ourselves again in 2019, we might think differently. But it worked for us and now, when someone says Guerrilla Girls, they know exactly who we are.

How many of you were there when you started back then?

There are all kinds of stories about that and some older members said there were seven. I am the original member and the first meeting happened at my house. And to be honest, I know we were a small working cadre, though I can’t remember the exact number — I would say we were 10, or fewer. Since then, we have had about 50 members.

So we would just hang out near the posters and listen to what people said and everyone was aghast Image: guerrillagirls.com

Starting out in New York, you have now transcended boundaries. Did you anticipate it?

We never had the plan to do that. We were just kind of angry and wanted to find a new way of talking about the situation and we really wanted to put people on the spot for participating in this system. I think we were helped by our anonymity and our humour. We have always wanted to transform people’s minds. We just don’t want to say this is bad, we try to get it done in a way that it asks a question and then information is what makes it click. Thanks to the Internet, our work was travelling all over the world within 10 years. We have also been very dogged and committed to keep it all going.

To us, the success of our work is enough to keep us going. We don’t participate in the commercial art fairs — we have figured another way of living, which is to give talks, design exhibitions and sell posters and T-shirts.

I would say, in 2005, when we were invited to the Venice Biennale, that was the tipping point when we realised that institutions were getting the message and we were connecting with well-intentioned people who work inside the institution, who wanted change, too, and needed some kind of help.

Your mediums of protest have been fairly unconventional…

From the very beginning, we knew that we had to do something new to get people’s attention. We had to be provocative and get people a little shaken up. So that’s why we use the word “girls” because that made all the feminists sit up because we were reclaiming that word. You know, there was a lot of opposition in the early feminism movement against using that word and for good reason, as it was oftentimes used by men to infantilise women. So we decided to call each other “girls” so it couldn’t hurt us any more. And then we were “guerrillas”, which means freedom fighters — an impolite word of saying that we were secret infiltrators in the art world. I can’t say we had a five-year plan but we had an idea to figure out a way to make people think about something, every step of the way.

You have always used humour to your advantage…

Before the Guerrilla Girls existed, I remember getting together with Kathe, who was a friend of mine and we would make fun of the art world because that would make us feel good. We realised that sometimes humour is the only revenge of an oppressed group. But when we started using humour at work and realised that it had an actual power to communicate, we also realised that if you can make someone who disagrees with you to laugh at an issue, you kind of have a hook inside their brain. And when you got their attention, you can slam them with some information, you have another chance to change their minds.

There’s also a thin line between activism and art and what you guys do marries the two. What are some of the pros and cons of that?

Well, I don’t know of any cons! (Laughs) I think that art has always been political, in one way or another, whether it supports the powers that be or it confronts the powers that be or if it tells the story of what’s going on in the culture. So I don’t see a distinct line between arts and politics and if you look at modernism, that’s truly the case, although I think certain formalist history of modernism tends to provoke the idea that art is formal. I don’t think that’s true because if you look at the essence of art anywhere, it has only been this sort of a utopian idea that art can make the world better, even if that was by changing consciousness.

What are some of the challenges you face?

We have been working as a collective for over 30 years and artists are not educated to work together. They are educated to fit the modern trope of the artist as an angry, crazy individual. So we have had to learn to work together, and I think that has a lot of difficulties. People have been in and out of our group, we have had people quit angry, we have had people quit happy. Anything that could have happened has happened. Imagine being married to 50 people for 30 years! (laughs) We have sort of been able to just keep it going — to change, to adapt and to look at another direction, to have ups and downs. But she persisted and that is our biggest accomplishment. When we first started, everybody hated us. And now, a lot of the influential institutions that we criticised are asking us to do things for them. Personally for me, I think the biggest challenge is to not get used by the system.

You have also managed to stay anonymous…

I think we are helped by the fact that no one really cares about who we are anymore because there’s no value in knowing who we are. The most difficult part of being anonymous is personal. I have a whole part of my life that I cannot be open about and I spend my days speaking to people under another name. That has some pros because we all want an alter-ego, but over time, it is kind of difficult. Sometimes it can be a little lonely and sometimes, it’s annoying because the same people love you when you’re a Guerrilla Girl as opposed to when you’re yourself. It just shows the different faces of the art world because they don’t treat everyone the same.

How have you expanded since the first group?

The bad news is that it’s really impossible for us to accommodate everyone who wants to work with us. But the good news is that you don’t need to be a Guerrilla Girl to work like we do. Get your crazy group and call yourselves something crazy but the world really needs more feminist-activists mass ventures than the Guerrilla Girls.

Our membership is fluid because sometimes our work is busier than at other times and we usually find like-minded people with the skills we need.

What are your favourite works done by the collective?

I like the books that we have done because they stick around and are an opportunity to do more than single, one-line captions on posters. It really is an in-depth analysis of a certain circumstance.

From your visit to India, what do you think needs protesting urgently?

I think the #MeToo movement is extremely important and it needs to be thought about and men have to realise it’s on them, too, and it cannot just be women protesting. And the anonymity of the accusers must be respected the way our anonymity was respected.

When we go to places, we can’t tell people what to do, we can only talk about what we have done and help them have courage to find their own ways to confront their justices.

What are you guys doing next?

We have a very active website (guerrillagirls.com) and we are working on a really important publication that will come out a year from now and we have exhibitions that are travelling. We are always happy to send our work. And it’s so exciting to see our work in Asia and South Asia. We are trying to expand our message in as many ways as possible.