Why do we love to see childhood photographs of ourselves? We are fascinated by the changes that the claws of time have wrought on our faces. Everything that was so familiar is decomposing and disintegrating with time.

The same is with old photographs of cities like Calcutta. We seek out similarities with the Calcutta of our times even when it is unrecognisable. Many of the photographs displayed at the exhibition, The City of Calcutta & Its Life: 1870-1920, held at the Town Hall were familiar enough, but some were unseen. Biplab Roy, the administrator-general and official trustee of Bengal, had discovered these along with other old documents and glass negatives on the ground floor of his New Secretariat Building office in 2021. It had remained closed for almost 40 years. About 400 prints were found. As many as 70 digital prints of those were on display.

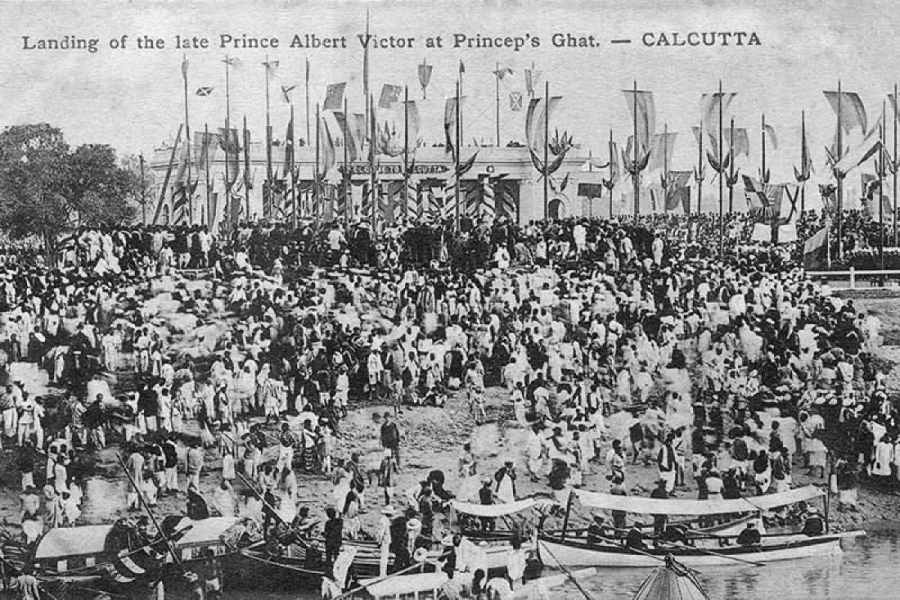

This treasure trove demands professional handling. Some captions need to be corrected, but the images were fascinating nonetheless. Most of the photographers remain unknown. The images show both ‘white’ and ‘black’ Calcutta. A hand-coloured print by Frederick Fiebig exists of Prinsep’s Ghat (even the Brits spelt it wrong) when the Hooghly flowed close to it. The one on display is of the masses waiting for the landing of Prince Albert Victor at the same spot. It is of 1889 vintage. The irony of it is that while the fluttering buntings and regalia are pushed well into the background, the kutcha foreground is dominated by innumerable ‘natives’, including the boatmen and their vessels.

The photographs of the palaces constructed by Wajid Ali Shah, when he settled down in dingy Metiabruz after the British usurped Lucknow, are with his descendants. The exhibited image of one of the light and airy palaces he built here is, undoubtedly, rare. With its sloping roofs, verandahs and lace-like railings, it was a concoction worthy of a fastidious king who loved the arts but couldn’t deal with politics. The British destroyed the palaces after his death.