The third and last part of 12 Masters, CIMA’s expansive showcasing of a dozen artists who have shaped the course of modern art in India and whose journeys reflect the birth and the evolution of the republic, moves from neorealism and social realism Towards the Personal (on view at CIMA till April 13). The four artists featured in this edition are Somnath Hore, Sarbari Roy Chowdhury, Lalu Prasad Shaw and Sanat Kar.

A shy teenager in pigtails with her arms folded across her chest — Roy Chowdhury’s Rinku — greets the viewer stepping into the gallery. This nearly 30” bust, placed at eye-level with the viewer, hints at a kind of familiarity and closeness that marks the rest of the show. Bringing together a range of works, this exhibition revisits the manifold aspects of Roy Chowdhury’s aesthetics as it imbibed cubist, realist and abstract elements to emerge as a unique amalgam of all three styles. Much like James McNeill Whistler, Roy Chowdhury’s art had a vision of the musical sublime — heads of Siddheswari Devi, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Ali Akbar Khan are caught mid-song as the human imperfections of their faces stand out in contrast to the flawless grandeur of their melody. The smooth shapes of the smaller sculptures seem as if they have been rolled out of clay and not cast in bronze (picture, left). The pensive figures crouched all alone and the grotesquely misshapen female bodies carry the imprint of the living hands that fashioned them; the technical exigencies of the lost-wax process and bronze-casting are dissipated in their vibrant humanity.

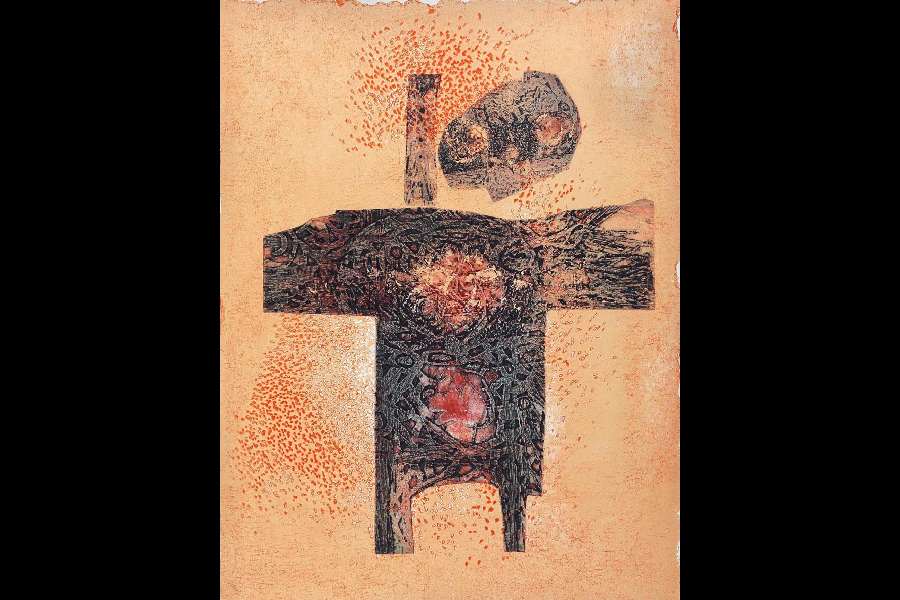

Humanity is also the moving spirit of Somnath Hore’s oeuvre. Having witnessed human suffering up close, he distilled it into prints of luminous clarity in his Wounds series, which had white-on-white paper pulp prints made from clay or wax sheets that he slashed and lacerated, forcing viewers to face and feel the wounds. In this show, Wounds-56 and Wounds (picture, second from left) were displayed against a flesh-toned wall, adding greatly to their impact. A consummate artist, Hore needed no symbolism, no rhetoric, no demonstration of ingenuity. His intimate sculptures with rough textures, unfinished surfaces and gaping spaces are poignant reminders of the traumas that left deep imprints on his mind. As the eye travels over the blistered skin, the torn flesh, the hollowed insides, the splintered bones, these traumas are brought alive for the viewers.

Somnath Hore, Wounds, Pulp Print (Variation Proof), 1983 Source: CIMA Gallery

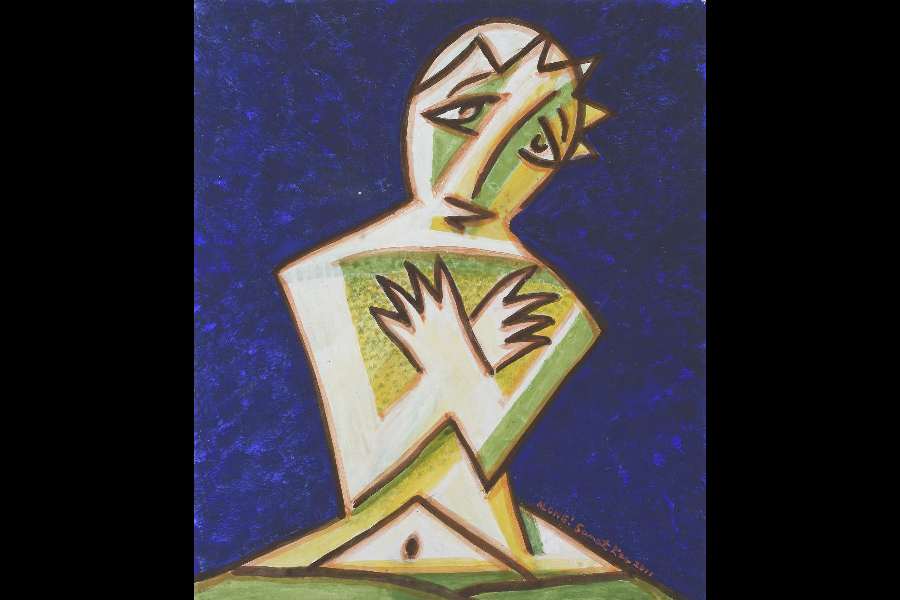

The bare realism of Hore gives way to the more personal and playful exploration of the human condition by Sanat Kar. Central to this exploration are eyes — whether in

the sparse lines of his pioneering wood intaglios or in the sprite-like figures that flit across his paintings done in tempera and other media, it is the eyes that draw the

viewers in (picture, third from left). Spare yet fluid lines effortlessly bend to form figures that are spontaneous yet fitful, while negative space and free-flowing cross-hatching are used to create a mysterious and sullen atmosphere around them. In his hands, even inanimate objects are turned into sentient beings where cups, furniture

and clothes sprout eyes, hands and legs and are ‘arranged’ in a surreal tableau as

in the Ikebana series.

Sanat Kar, Alone!, Tempera, 2011 Source: CIMA Gallery

The line is the muse for Lalu Prasad Shaw. It takes a life of its own, whether in his signature portraits of Babus and Bibis or in the brooding, bold, abstract, geometric etchings and lithographs (picture, right). Shaw’s figurative paintings, in which the styles of Kalighat pats and Mughal miniatures coexist seamlessly, are charged with nostalgia.

Lalu Prasad Shaw, Untitled, Color Etching - 9/14 (A/P), 1993 Souce: CIMA Gallery

Brooding characters are frozen into quiescent gestures and often livened up by Shaw’s sly sense of humour. The depth and the wideness of Shaw’s body of work, often overlooked in favour of his later, figurative creations, was on display at this show.