Somenath Hore’s images bore the brunt of the anguish and trauma he experienced as he observed mindless bloodshed and savagery all around him.

The broad, calligraphic strokes of his brush dipped in ink and the lightning sketches with his pencil and pen brought alive on paper quotidian reality and the compositions he had in mind. He occasionally used the pages of cheap diaries or other scraps of paper for these exercises. The very act of making precise incisions on metal plates for etchings, gouging an image on a block of wood for woodcuts, and drawing a mirrored image on a flat stone or a prepared metal plate for a lithograph, literally and metaphorically transferred the violence, trauma and despair the artist witnessed on the matrix created for making multiple prints. Instead of being mere symbols, the gashes on his white on-white prints turn into raw and gaping wounds dripping blood.

A wealth of more than 200 drawings and prints, many of them rarely seen, were displayed at Akar Prakar’s outstanding exhibition, Somnath Hore 100 (August 26-October 15), which was organised to celebrate the centenary of the master known for his simple lifestyle and unassuming nature, which reflected in his art of the barest essentials.

The brutality, cruelty and barbarism that Hore (1921-2006) witnessed during the Japanese airstrikes in his village in Chittagong and the devastation of the 1943 Bengal famine had a deep and lasting impact on the artist. He was inspired by Chittaprosad, the autodidact, and later, after joining the Calcutta Art School, he grew close to Zainul Abedin. Both were known for their harrowing documentation of the 1943 Bengal famine. Hore was an active member of the Communist Party of India, and even though he severed ties with it in later life, he remained a leftist at heart. His dramatic documentation of the Tebhaga movement had already been noticed, although he was still an untrained artist. At the art school, Hore was drawn to Safiuddin Ahmed and his powerful wood engravings. Socialist Chinese propaganda images drew Hore’s attention. The German Expressionists caught his eye, but it was a compassionate and committed Käthe Kollwitz who grew on Somnath Hore.

The works exhibited were executed between the 1960s and 1970s, around the time that Somnath Hore had joined Santiniketan to head the graphic and printmaking department in 1969.

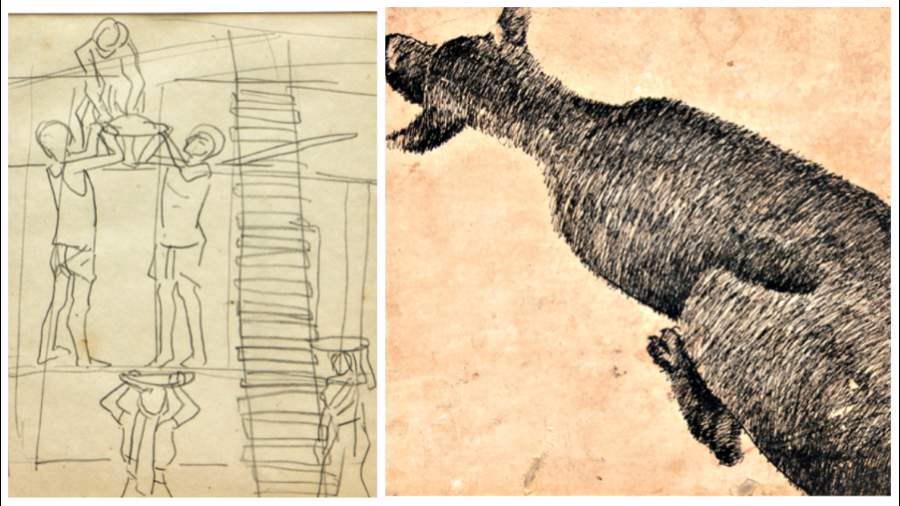

Male and female workers at construction sites (picture, left), some with the mask-like heads of his sculpted figures, portraits, a heavily pregnant goat, mating dogs, a crow swooping down on a morsel, skeletal strays, jagged lines defining human figures in various postures, a man about to violate a woman essayed with a few fluid strokes of his pen, a canine body fleshed out with dense cross hatching stretched diagonally across a sheet of paper (picture, right), the armature of sculptures that came later — all of these were expressed through an economy of lines. Many of these drawings — preparatory sketches probably — seem to have been done on the spot, capturing with amazing exactitude the truth of the moment.

The human battlefield exploded on the surface of his graphic works with a flurry of lines, occasionally with a splash of red and grey. In striking contrast are the images of oppressed humanity drained of the power to fight back. In between are haunting visions of ineffable beauty that only come true in dreams.