Even talented artists who enjoyed success and fame in their lifetime can sink into oblivion unless their children or other members of their family or friends choose to revive their memory by holding exhibitions or launching publishing projects on their art. Samarendra Nath Ghosh (1912-1995) is one such forgotten artist whose exhibition was held at the Academy of Fine Arts earlier this year.

This seems to be a lucky year for artists who have fallen off the radar, their virtuosity and brilliance notwithstanding. The second such in Bengal was Lalit Mohan Sen (1898-1954), an exhibition of whose paintings, drawings and remarkable photographs titled Lalit Mohan Sen: An Enduring Legacy is now on at Emami Art till September 30. It was curated in consultation with Debdutta Gupta.

Sen’s strong suit was his training in academic realism at the Government School of Arts and Crafts in Lucknow which he joined in 1912 after leaving his hometown, Shantipur, during an outbreak of malaria. Later, he had taken up commercial art. He joined the Royal College of Art in London in 1925 on a government scholarship under Sir William Rothenstein. He excelled at oil painting, watercolour, crayon and pastel, and graphic art, including etching, woodcut, linocut, design work as well as sculpture. An exquisitely carved female head of wood is displayed in this exhibition. His woodcuts of Rabindranath and Gandhi are part of the V&A Museum’s collection.

When he returned to Lucknow, he joined his alma mater and taught there for 25 years. He was appointed its principal in 1945. His training in Western academism notwithstanding, he had no quarrel with traditional Indian art. The outline drawings of Hindu deities and watercolours based on the life of Christ and another of women musicians performing on a terrace in a garden are proof enough. The latter conformed to the Bengal School style. This was an affirmation of the nationalistic streak in him even though he never openly supported the freedom movement.

Because of his mastery in both styles, Robert Laurence Binyon, the English litterateur and art scholar, commissioned Sen to copy the Bagh Cave paintings. In 1930, he was among the four artists commissioned to decorate the newly-built India House in London. He painted murals depicting Buddha’s disciple Ananda and Akbar scrutinising the Fatehpur Sikri plan. While most details of his career are documented in Kamal Sarkar’s invaluable, but out-of-print, Bharater Bhaskar O Chitrashilpi, the bulk of Lalit Mohan’s art was in the care of his grand-nephew, Prabartak Sen.

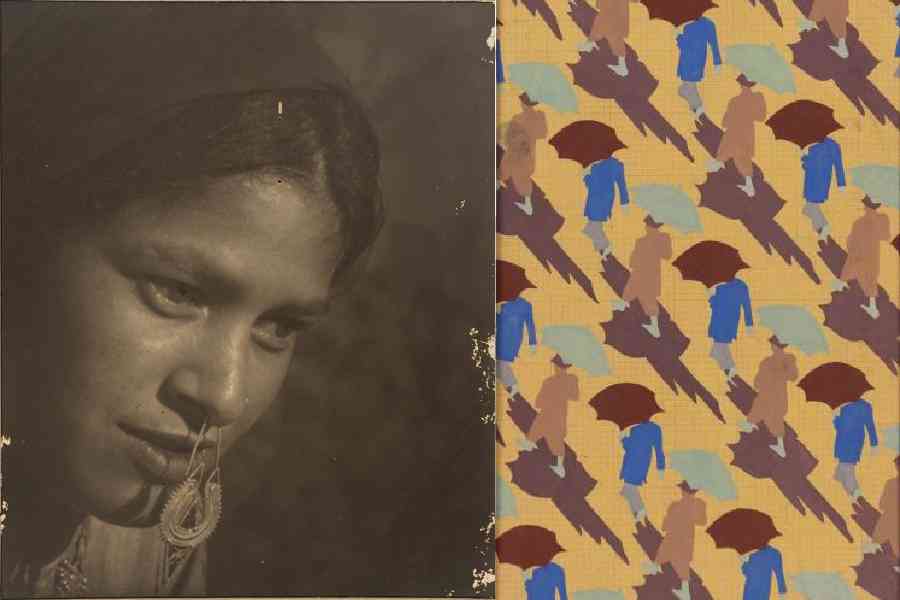

In this exhibition are displayed various portraits (including one of Hitler), landscapes, life studies, promotional material, graphic prints (picture, right) and sensitive photographs. While as an artist, Lalit Mohan was hidebound in spite of his considerable skills, as a photographer, he came into his own. An indefatigable traveller, his constant companions were his notebook and his cameras, a Vest Pocket Kodak of 1910 vintage and a Leica. These, along with some other personal effects, are on display.

It was only in the United Kingdom that he started using the camera and his wonderful black-and-white silver gelatin prints, which are still in perfect condition, were part of the Royal Photographic Society’s annual exhibition and its journal. Lalit Mohan Sen’s photographs of nudes have the angularity of sculpture. However, it is his close-ups of simple village folk that are outstanding for the innocence that shines through (picture, left).