Who were the luminaries that lit the path that modern Indian artists walk on and what were their inspirations? CIMA has been trying to shed light on these intriguing and important questions for three decades while making art more accessible. The celebration of its 30th anniversary follows in this tradition, with a series of exhibitions stretching across six months. The inaugural show, 12 Masters - Fantasy to Subliminal (on display at CIMA till January 20), begins at the very core: the Indian psyche shaped by the tumultuous birth of the nation and its life thereafter. The first sight that greets viewers at the gallery are four works that cover a rather wide spectrum of artistic grammar and inspiration, allowing them to dip their toes, so to speak, into the idioms of the four masters — Arpita Singh, Ganesh Pyne, Sushen Ghosh and Shreyasi Chatterjee — whose works they are about to encounter.

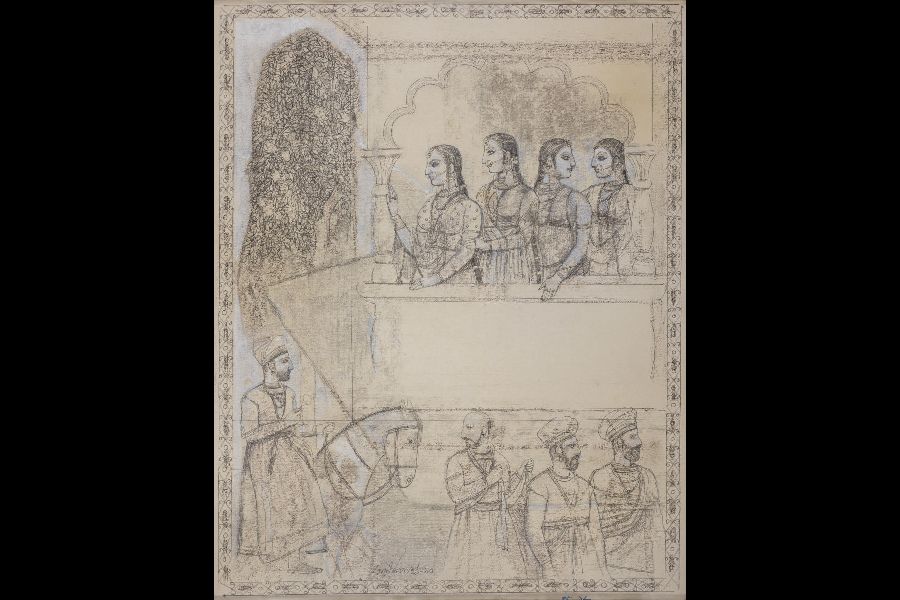

Ganesh Pyne was an impressionable child during the chaotic, violent years of Indian Independence. These early years ground Pyne’s art in dark, unsettling images, drawn from mythology and dreams. Skulls, skeletons, piercing arrows and phantasms indicate a vision of the world, that was, above all, tragic. Primary colours are rare; instead, there are amber browns and ashy blues in overlapping layers. Bodies often seem lit from within, as if they are burning from inside out. While the mystery that shrouds Pyne’s vision continues to intrigue, the poignance of the Metiabruzer Nawab series — done as illustrations for a book by Nikhil Sarkar — was a rare treat (picture, left). Mixed-media sketches on paper evoke the feel of vivid miniature paintings, but in keeping with the trials and the humiliation of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the works are in monotone with smudges of dull gold — as if the sheen of the nawab’s rich past is being sanded away bit by bit.

An artwork from the series, Metiabruzer Nawab, by Ganesh Pyne CIMA

In contrast was the glint of some of Sushen Ghosh’s sculptures, such as Monument and Composition 1 to 8, which refract light to add a sense of movement to these works. Ghosh’s innate sense of rhythm — he was an accomplished flautist — was sharpened at Kala Bhavana by Nandalal Bose and it is evident in the way his sculptures are structured and formed out of carefully balanced components like musical notes. Like a musical piece that ebbs and flows, swells and wanes, but is held together by an innate rhythm, sculptures like Growing Space (picture, right) form lyrical compositions. Ghosh’s eloquent bronze sculpture of his other teacher, Ramkinkar Baij, best exemplifies the latter’s teaching of coaxing emotion and expression out of metal.

The expressions of Arpita Singh’s subjects are telling even though they do not give much away — their visages are cloaked; yet they convey their jaded selves. Women going about their daily tasks and the pitfalls that they have to encounter in the process, while men take the Smooth Route through life, wielding power in the form of a gun, are the subjects that fascinate Singh the most. In her paintings, numbers, alphabets, words, and phrases, compete with human protagonists and their attendant verdure, add new dimensions to the works. With their wealth of detail and deeply texturised watercolours, Singh’s densely wrought surfaces recall her stint at the government-owned Weavers’ Service Centre in the 1960s.

But none plays better with textile, texture and details than Shreyasi Chatterjee in her idyllic, whimsical pieces. Chatterjee, a professor of art history besides being a practitioner of art, does not let theory eclipse her practice. Her use of stitches harks back to the indigenous traditions of embroidery employed in nakshikantha. However, she appropriates this process to suit her unique collage of appliques of varied shapes and colours. The eyes have to constantly realign themselves with each bit of the canvas to uncover tiny, hidden dioramas unfolding in every corner. Beyond this busy snapshot of the bustle of everyday life often lies a luminous expanse of sky which lingers in the mind.