Centenary shows can often end up being either catalogic or hagiographic. But One Hundred Years and Counting: Re-scripting KG Subramanyan (hosted at Emami Art by Seagull and Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University, Baroda, in collaboration with the Kolkata Centre for Creativity), curated by the cultural theorist, Nancy Adajania, deftly sidestepped these templates by abjuring both the thematic and the chronical approach while revisiting the works of the master artist who was known for his pluralistic vision.

At a time when Indian democracy stands at a crossroads, Adajania chose to focus on the strong political elements in Subramanyan’s work. Moreover, to situate Subramanyan in the history of Indian art and explain his seminal influence on it, the curator included in the exhibition some of Subramanyan’s teachers as well as students. This created a fascinating montage — of art in newly-independent India, of Kala Bhavana’s influence on Indian art, of the intermingling of indigenous traditions from across the country and of the role that gender played in shaping the sensibility and the vision of an artist.

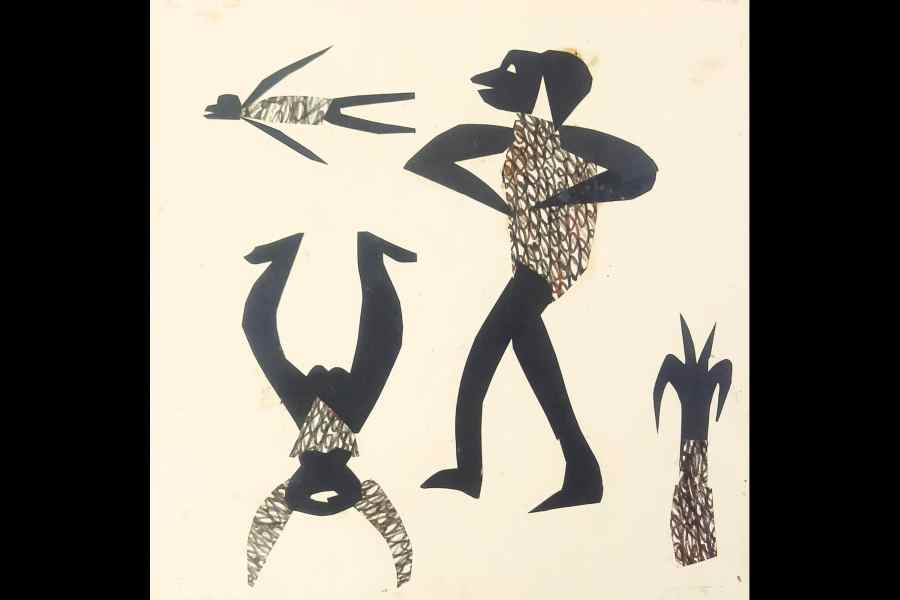

A page from How Hanu Became Hanuman [Emami Art/Seagull and Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University, Baroda]

Among the works that captured Subramanyan’s political philosophy, the most striking was perhaps The City is Not for Burning (picture, left), drawn in 1993 as a response to the communal Gujarat-Bombay divide. Significantly, Adajania included the artist’s works for children, such as The Tale of the Talking Face, a book written and illustrated by Subramanyan, in which he offers a stinging parable of democracy gone wrong by narrating and illustrating the story of a princess whose autocratic rule brought nothing but suffering to her people (a response to the Emergency). Cut-outs from this title and of Robby, a character from Subramanyan’s books who is thought to be the artist’s alter ego, were blown up in size and pasted all across the walls and the floors of the gallery, guiding the viewers’ path. The inclusion of what is often dismissed as being intended for children is important because the experience of seeing the country turn into something that was not envisioned at Independence made Subramanyan aware of the need to communicate his ideals to the next generation. In this context, children of present-day India might benefit immensely from his book, How Hanu Became Hanuman (mock-ups from which were on display, picture, right).

The show also highlighted just how versatile Subramanyan was — be it his hurried strokes on postcards, his signature reverse paintings, toys he made for the Fine Arts Fair or his famous marker pen works on paper, his gouaches and his murals, the exhibition covered a wide arch. What tied these diverse media together was the inherent sense of drama in the vision of an artist who revelled in the charm and the charisma of the historical arts of India. In each frame, one could rediscover the artist-pedagogue who could keep up with the world as well as preserve the cultural identities of the many characters that visited his works.